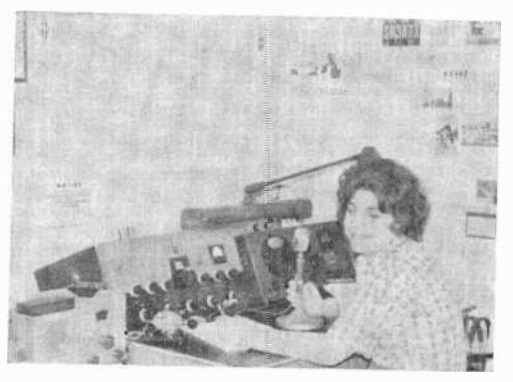

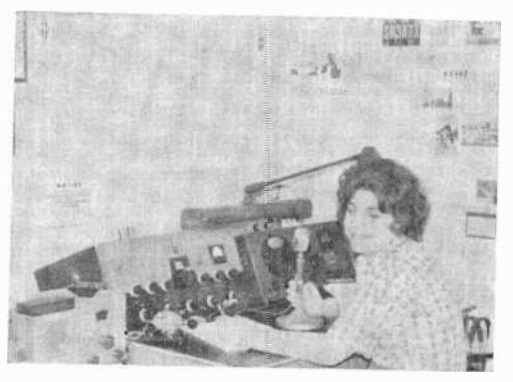

Shown here, from the September 1961 issue of Popular Electronics, is Barbara Slutzkin, WV2PZH, 1225 Ave. R., Brooklyn, New York.

Shown here, from the September 1961 issue of Popular Electronics, is Barbara Slutzkin, WV2PZH, 1225 Ave. R., Brooklyn, New York.

She was a Junior at James Madison High School, where she was a member of the school radio club, and thought more girls should become hams. She is shown here at home, where she had a Viking II transmitter and Hallicrafters SX-25, as well as gear for 2 meters. According to the magazine, her pride and joy was her homebrew electronic key.

She is shown holding a microphone, so she was presumably operating two meters, the only band on which novices had voice privileges at the time. According to the magazine, her well-equipped station included a beam antenna for that band.

After a good start, and despite an excellent home station, it appears that Ms. Slutzkin didn’t continue with amateur radio. Her novice license would have been good for one year, and she would have needed to upgrade to Technician or General in that time. Upon upgrade, her call would have become WA2PZH. Unfortunately, the 1962 edition of the callbook doesn’t show that call listed, and there’s nobody by her name listed in the second call area.

We understand that people Google their own names, so if Ms. Slutzkin happens to read this, we always enjoy hearing from people we’ve featured. Did you continue in ham radio? If not, even though your license lapsed, there’s nothing stopping you from getting a new one! Feel free to leave a comment below, or e-mail us at w0is@arrl.net.

Eighty years ago this month, the September 1941 issue of Radio Retailing carried this ad for Emerson’s lineup for the coming model year. It turns out these would be the last models made until 1946, as civilian radio and phonograph production ended for the duration on April 22, 1942.

Eighty years ago this month, the September 1941 issue of Radio Retailing carried this ad for Emerson’s lineup for the coming model year. It turns out these would be the last models made until 1946, as civilian radio and phonograph production ended for the duration on April 22, 1942.