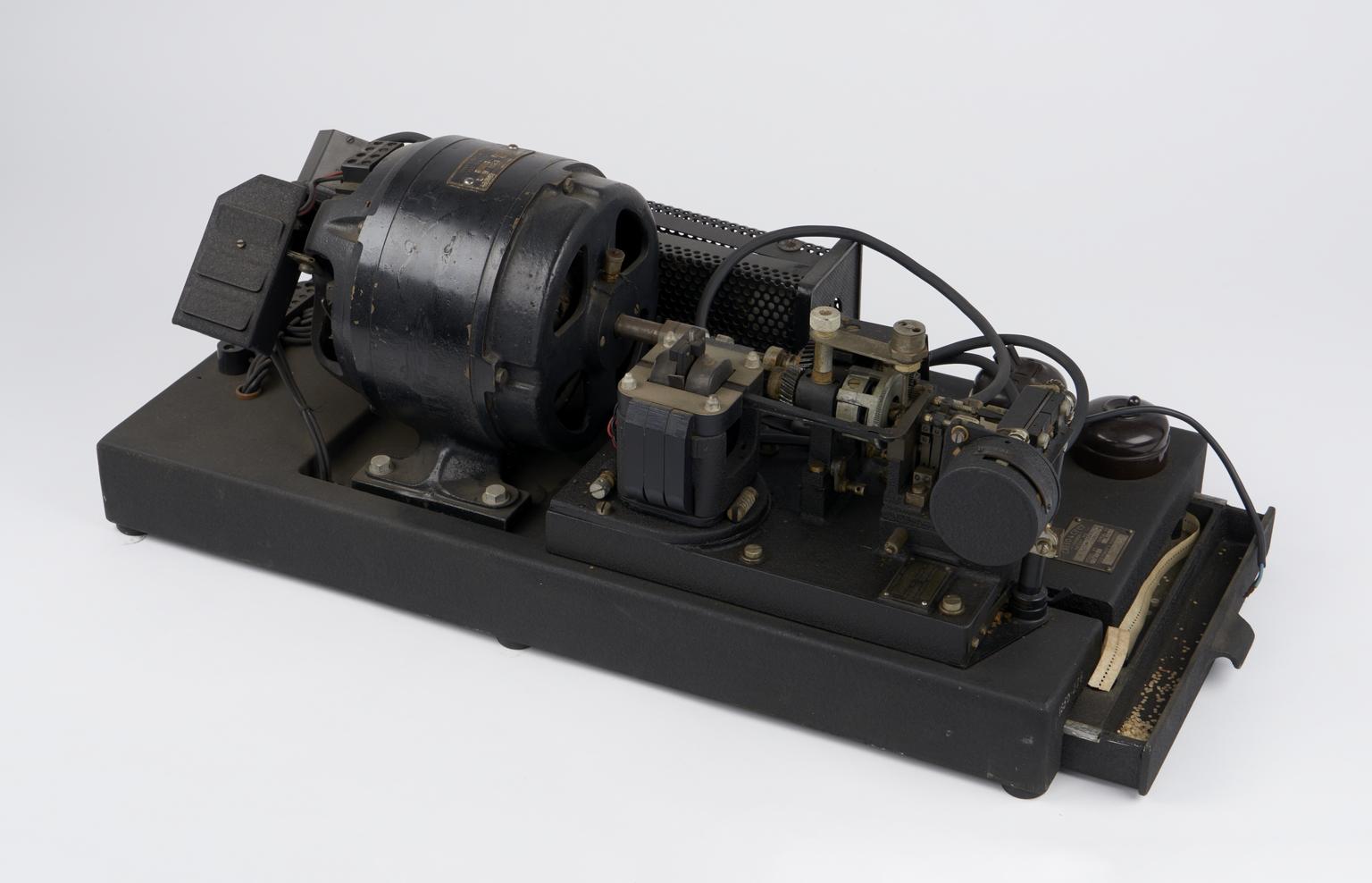

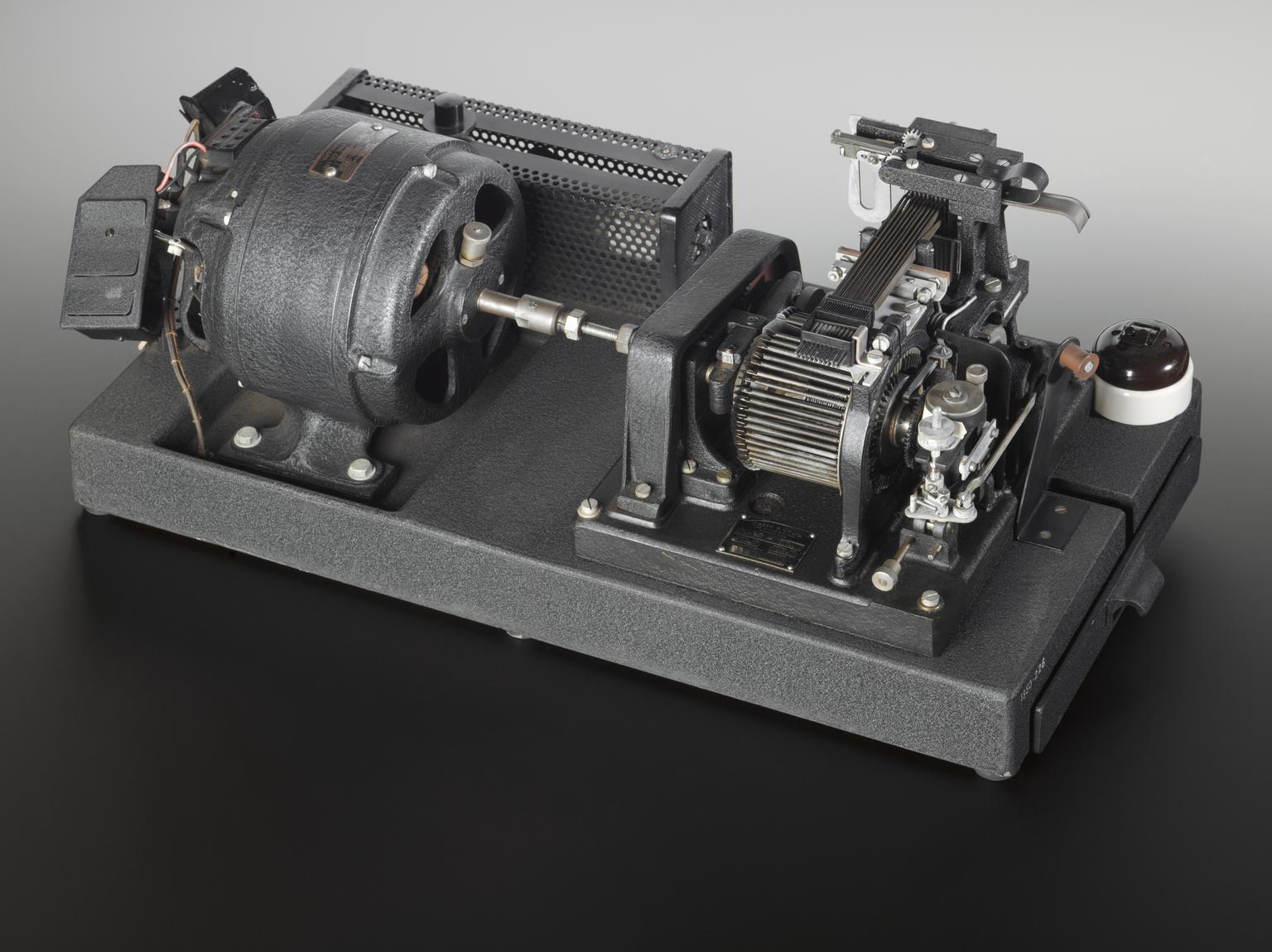

Creed No. 7W/3 Reperforator (1925). Image courtesy of Science Museum Group Collection, © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum, U.K. released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

No. I.T. Morse Tape Printer (1925). Image courtesy of Science Museum Group Collection, © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum, U.K., released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The two devices shown above represent a hundred year old method of automatically decoding International Morse Code. They, along with the sending device, are described in the March 1921 issue of Radio News.

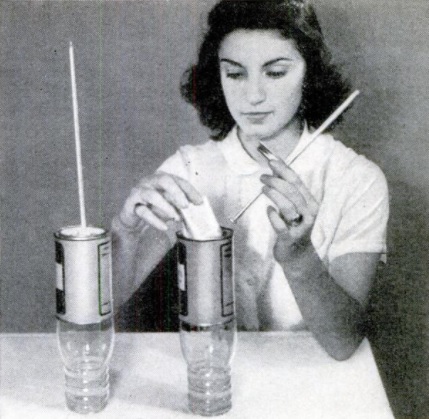

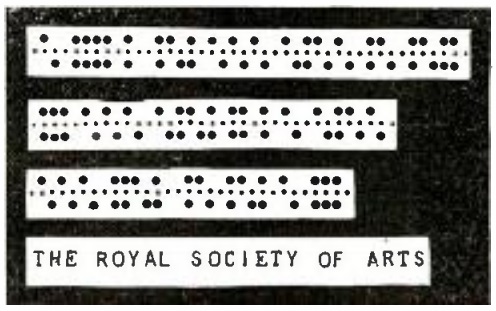

At the sending end, the message is typed on a typewriter-like keyboard and punched onto a paper tape. An example of the tape is shown below. It’s not immediately obvious that the tape contains Morse code, but upon closer observation, it is. A “dot” is indicated by one hole directly above another hole. A “dash” is indicated by two holes that are slanted. Once you see this, the Morse code is obvious. The first word shown here is “the.” The first two holes are slanted. This is a single dash for the letter T. This is followed by four sets of holes, one directly above the other–four dots, for the letter H. Next, there is a single set of vertical holes, another dot for the letter E.

At the sending end, the message is typed on a typewriter-like keyboard and punched onto a paper tape. An example of the tape is shown below. It’s not immediately obvious that the tape contains Morse code, but upon closer observation, it is. A “dot” is indicated by one hole directly above another hole. A “dash” is indicated by two holes that are slanted. Once you see this, the Morse code is obvious. The first word shown here is “the.” The first two holes are slanted. This is a single dash for the letter T. This is followed by four sets of holes, one directly above the other–four dots, for the letter H. Next, there is a single set of vertical holes, another dot for the letter E.

Once this tape is produced, it is sent through another machine which keys the transmitter and sends the Morse signal over the air.

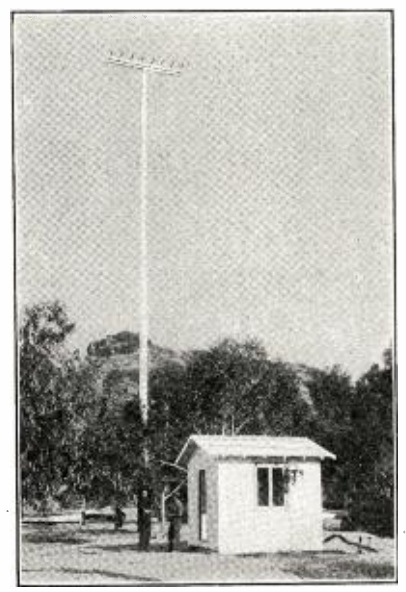

At the receiving station, the two machines shown above are used to receive and print the message. The reperforator (top) connects to the receiver and produces an exact duplicate of the paper tape. Then, the paper tape is fed into the Morse Tape Printer, which prints the message on a paper tape.

The process was known as the Creed Automatic System, named after inventor Frederick G. Creed, an important figure in the development of the teleprinter. At the beginning of the 20th Century, Creed was told my none less than Lord Kelvin that “there is no future in that idea.” Undaunted, he managed to sell twelve machines to the British post office in 1902. The 1921 machine described for use with wireless telegraphy appears to be a variation of that device.

By the late 1920s, the company was producing teleprinter equipment using a variant of the five-bit Baudot code. The company became part of IT&T, and Creed retired from the company in 1930. Among his later projects was the “Seadrome,” a floating airport which could be placed along international air routes. The project is described in a March 1939 article in the Glascow Herald, and was undoubtedly a casualty of both the War and increased aircraft range. The Seadrome is the subject of US Patent 2238974, applied for in February 1939 and granted in April 1941.

The images above are copyrighted and provided courtesy of the Science Museum Group, U.K., where they are on display, and released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.