We take unwarranted criticism of the U.S. Postal Service very seriously around here. As we reported previously, the Post Office stood ready to serve the nation even after a nuclear war, and during COVID-19 the men and women of the USPS have acted heroically to ensure that the mail goes through. Even when rioters burnt down two post offices in Minneapolis, the Postal Service quickly regrouped to make sure that its customers would continue to receive mail with minimal interruption.

We take unwarranted criticism of the U.S. Postal Service very seriously around here. As we reported previously, the Post Office stood ready to serve the nation even after a nuclear war, and during COVID-19 the men and women of the USPS have acted heroically to ensure that the mail goes through. Even when rioters burnt down two post offices in Minneapolis, the Postal Service quickly regrouped to make sure that its customers would continue to receive mail with minimal interruption.

Recently, for political reasons, the USPS has come under intense criticism, the gist of which being that they can’t do anything right. They were allegedly in the process of ripping out all of their sorting machines, and even removing mailboxes. The particular conspiracy theory was that without these sorting machines, they would be unable to deliver millions of ballots. This didn’t make much sense to us, since most ballots in a given locality would all be addressed to the same city or county election office, and wouldn’t require much sorting, by machine or otherwise.

And allegedly, the removal of mailboxes was to prevent voters from sending their ballots. The theory was that a voter would go to a spot where there used to be a mailbox, would see that the mailbox was gone, and then give up in despair. For the theory to work, the voter would have to be too dumb to look for another mailbox, take it to the nearest post office (where they would find a mailbox in the parking lot), give it to their friendly letter carrier, or just take it to the election office themselves. In short, as conspiracy theories go, it wasn’t very plausible, but a lot of people seemed to subscribe to it.

So as an experiment, I decided to test the United States Postal Service. I asked for volunteers on Facebook and NextDoor. I had them send me their address, and I mailed them an honest-to-goodness piece of snail mail. I had ten volunteers, and I asked them to inform me when they received the letter. I mailed the letters from three different locations. Some I mailed from a blue mailbox in front of a local strip mall (one of the boxes that was allegedly being torn out). Some I mailed from the drive-up mailbox in front of my local post office. And some I placed in my own mailbox, and the friendly letter carrier picked them up with the mail.

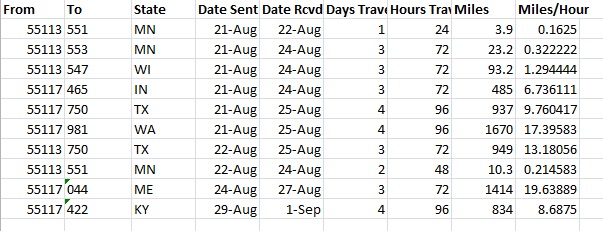

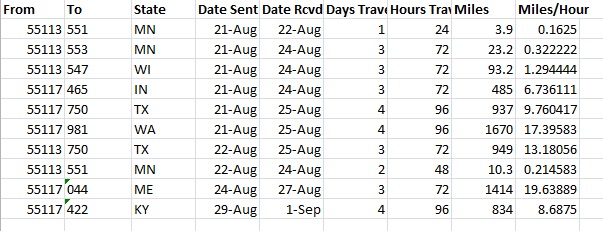

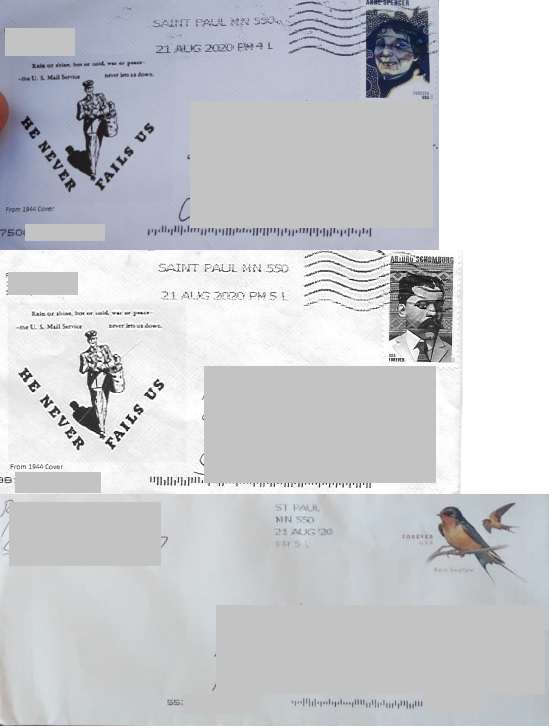

A small sampling of my letters is shown above. All ten were delivered in a timely fashion. Most of the transit times included a Sunday, but I included it. All ten of the letters were delivered in four days or less. Crosstown letters were delivered in either one or two days (the two day period included a Sunday). I tracked the average speed of each letter (measured by road miles from the center of the two ZIP codes). The slowest traveled an average speed of 0.16 miles per hour (845 feet per hour). That sounds slow, but keep in mind that I dropped it in a box in the afternoon, and there’s no way it could have arrived any earlier than the next day.

The fastest letter got from Minnesota to Maine at an average speed of 19.6 miles per hour. Remember, this included a Sunday, when it presumably didn’t travel at all. It was undoubtedly in multiple trucks during its trip. In my humble opinion, travelling at that speed for a mere 55 cents is an amazing bargain. Letters to Texas and Washington got similar excellent service. The full results are shown in the table below.

All of my letters were addressed by hand, and as my elementary school teachers would attest, my penmanship isn’t the greatest. But the post office managed to sort them. And all of the letters I saw had bar codes printed on them. These would have been printed on the envelopes by an automatic sorting machine, and they are designed to be read by other automatic sorting machines. These, of course, are the automatic sorting machines that the USPS allegedly ripped out and put on the scrap heap. But somehow, my letters all made it through one or more of these allegedly non-existent machines.

In short, the criticism of the USPS is unfounded. As they have done throughout the pandemic, as they have done despite civil unrest, they continue to serve their country proudly.

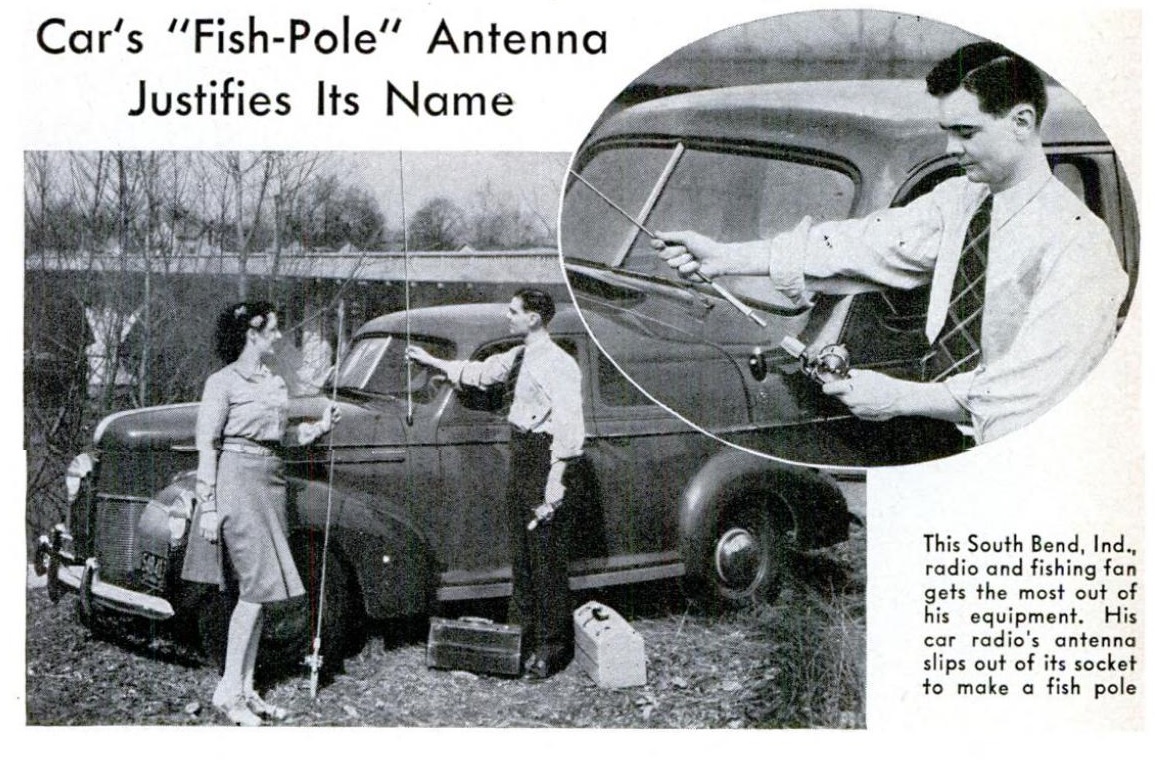

If you’re wondering about the design on some of the envelopes, I copied the design from a 1944 patriotic cover. (You can see that cover and read more about it at this link.) Just like they do today, during the war, the Post Office Department made sure that they mail went through. I’m sure there were detractors back then, but someone decided to print up some special envelopes to thank their letter carrier for heroic service.

We ought to do the same today. If you haven’t done so recently, thank your letter carrier for his or her hard work. And for the workers behind the scenes, you can invest 55 cents and mail them a thank you card. Just address it to “Postmaster” and your city, state, and ZIP code. I’m sure it will get pinned up to the employee bulletin board. They’ve worked hard to serve you, and they deserve your thanks.

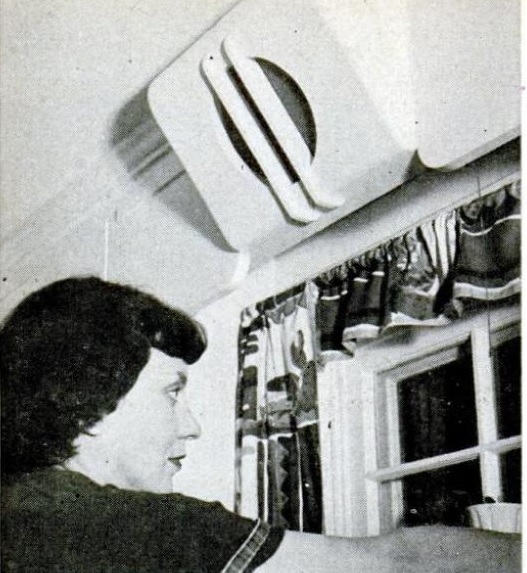

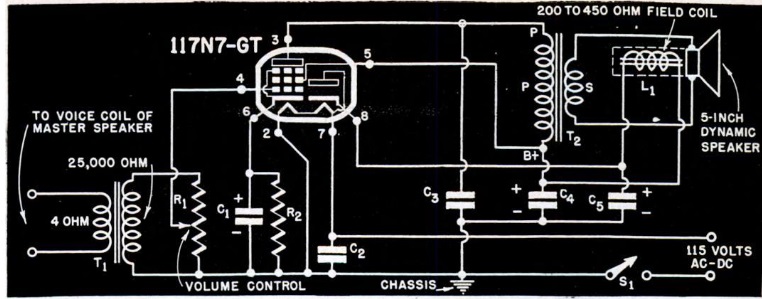

This woman is listening to the radio in her kitchen, but she’s doing it at the fraction of the cost of a new radio, thanks to the remote speaker described in the September 1950 issue of Popular Science.

This woman is listening to the radio in her kitchen, but she’s doing it at the fraction of the cost of a new radio, thanks to the remote speaker described in the September 1950 issue of Popular Science.

We take unwarranted criticism of the U.S. Postal Service very seriously around here. As we reported previously, the Post Office stood ready to

We take unwarranted criticism of the U.S. Postal Service very seriously around here. As we reported previously, the Post Office stood ready to