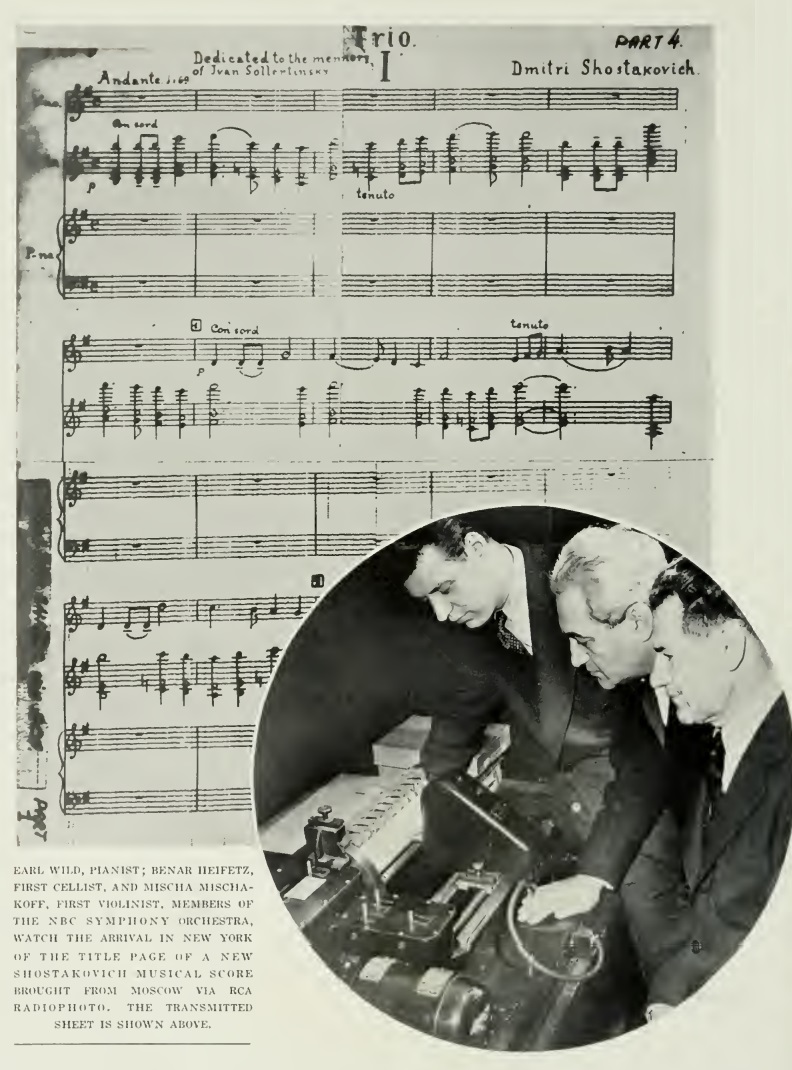

Shown here, in the April 1945 issue of Radio Age, is a musical score by Dmitri Shostakovich, sent from Moscow to New York via radio facsimile, and performed by the NBC Symphony Orchestra.

Shown here, in the April 1945 issue of Radio Age, is a musical score by Dmitri Shostakovich, sent from Moscow to New York via radio facsimile, and performed by the NBC Symphony Orchestra.

Shown here, in the April 1945 issue of Radio Age, is a musical score by Dmitri Shostakovich, sent from Moscow to New York via radio facsimile, and performed by the NBC Symphony Orchestra.

Shown here, in the April 1945 issue of Radio Age, is a musical score by Dmitri Shostakovich, sent from Moscow to New York via radio facsimile, and performed by the NBC Symphony Orchestra.

We wrote previously about Canadian airman Brian Hodgkinson. He was a former announcer for CKY Winnipeg, and was a German POW for most of the War. After the war, he moved to the United States where he was an announcer for WHK, WERE, and WDOK in Cleveland.

We wrote previously about Canadian airman Brian Hodgkinson. He was a former announcer for CKY Winnipeg, and was a German POW for most of the War. After the war, he moved to the United States where he was an announcer for WHK, WERE, and WDOK in Cleveland.

75 years ago this month, CKY’s program guide, Manitoba Calling, April 1945, carried this letter from a fellow POW:

Paris, 30 December, 1944.

Sir,

I would be very grateful to you if you could put me in touch with Brian Hodgkinson’s family. This request may appear somewhat indiscreet. Here is a brief exposé of the reasons which motivate my request.

We met in Stalag VII a in Germany, where, for many months, we were together and we became great friends. We were separated in the summer of 1942 following camp changes.

I had the luck of returning to France a year ago where I am enjoying absolute liberty, following the exploits of your armed forces and those of your allies. I would therefore be very happy to receive news of my gi and comrade, and he having communicated his address to

Radio Winnipeg, I, in turn, am taking the liberty of addressing myself to you.

I offer my excuses for having written you in French, but my knowledge of the English language is so restricted that it does not permit my use of it.

With my most heartfelt thanks, 1 offer you. sir, my distinguished salutations and the greetings of a Frenchman -friend and admirer of the Canadian people.

Lucien Villatte,

107 Rue du Chevaleret,

Paris 13, France.

Hodgkinson’s memoir of his days during the war, Spitfire Down, was published after his death. The book is not available in the United States, but used copies are available at a reasonable price on Amazon. In Canada, it’s also available at Amazon.ca.

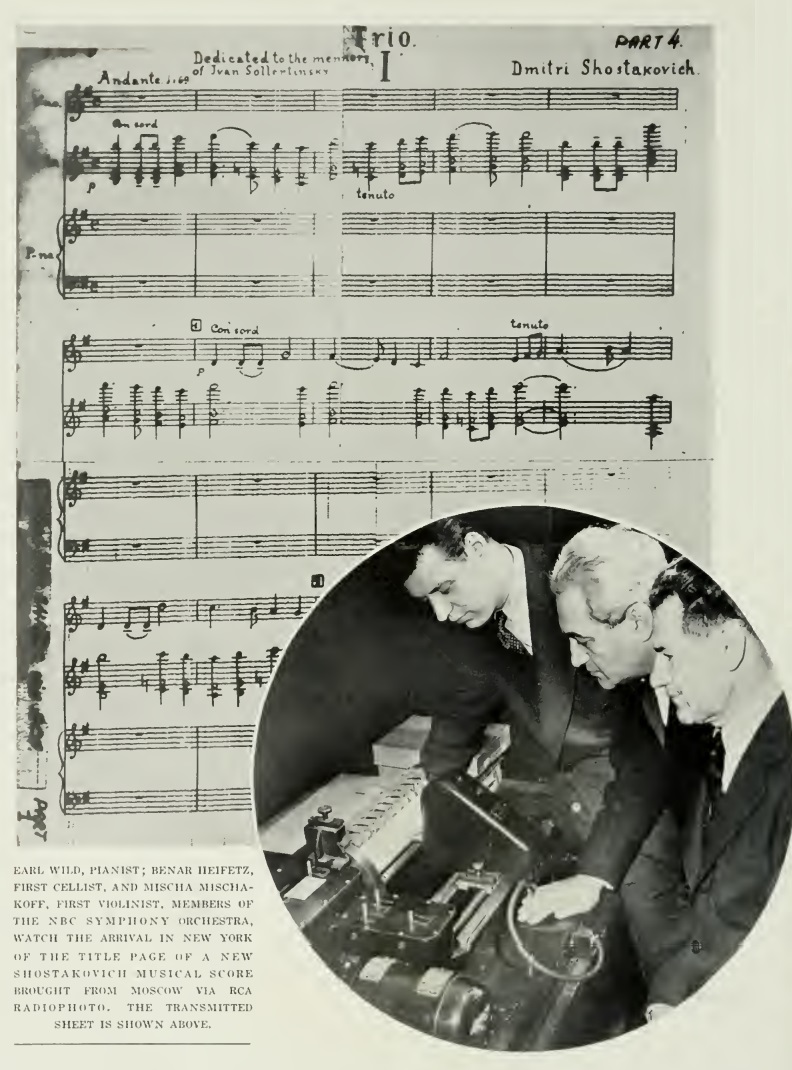

Virginia Capitol Disaster. Library of Virginia image.

150 years ago today, April 27, 1970, the chamber of the Virginia Supreme Court collapsed into the House of Delegates one floor below. Postwar military rule had ended in January, and a dispute arose over the leadership of the City of Richmond. The case was to be heard by the Virginia Supreme Court, and several hundred, including the two mayoral hopefuls, crowded into the courtroom. A gallery full of spectators collapsed, which in turn caused the main courtroom floor to fall 40 feet to the floor below.

62 were killed, with 251 injured. The dead included a grandson of Patrick Henry. Despite initial calls to demolish the building, it was repaired. The building still stands, with two wings added in 1904.

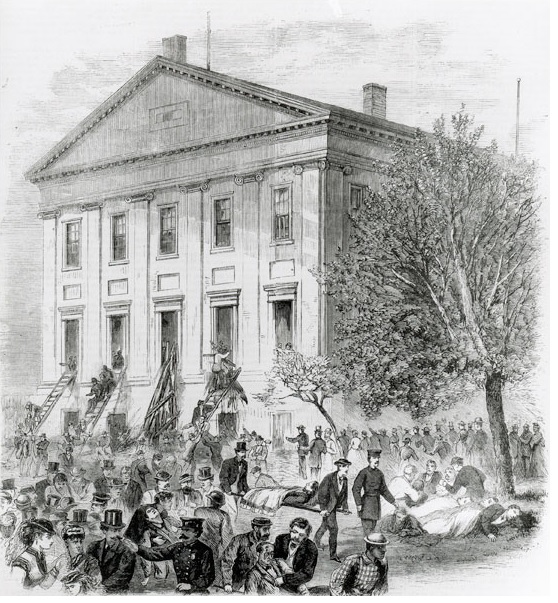

The musician shown here, under the watchful eye of J.S. Bach perched atop her radio, is an early adopter of the electronically amplified guitar. She has a small pickup microphone mounted on the guitar, which is fed into the boosting transformer shown. The output went to the radio’s phono jack, or if it didn’t have one, to the volume control.

The musician shown here, under the watchful eye of J.S. Bach perched atop her radio, is an early adopter of the electronically amplified guitar. She has a small pickup microphone mounted on the guitar, which is fed into the boosting transformer shown. The output went to the radio’s phono jack, or if it didn’t have one, to the volume control.

The picture to the right, while unrelated, shows a hint that is worth noting. The radio knob had come loose from its shaft. The problem was solved by adding a bit of solder to the shaft to build it up and ensure a tight fit.

The illustration appeared in the April 1940 issue of Popular Mechanics.

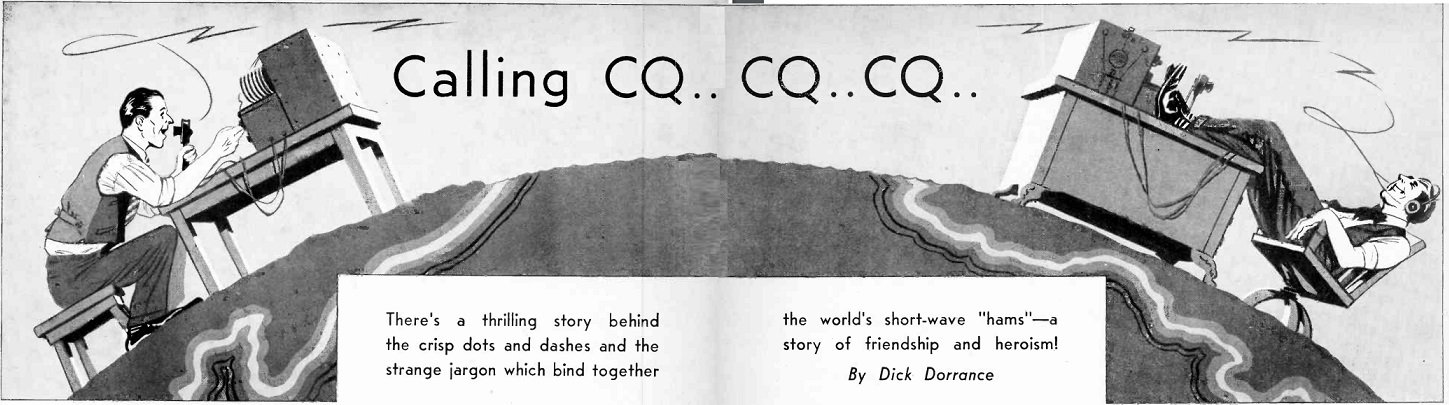

Broadcast listeners 80 years ago, while tuning the shortwave dial of their set, might occasionally have heard the sounds of “that fool kid down the block,” namely a ham radio operator, coming through the speaker of their console set. But this article, in the April 13, 1940, issue of Radio Guide reminds listeners that that fool kid was a member of an “old and honorable clan–a clan which, out of its own altruism and persistence, has helped give us the wonderful marvels of radio which today we take so much for granted.”

Broadcast listeners 80 years ago, while tuning the shortwave dial of their set, might occasionally have heard the sounds of “that fool kid down the block,” namely a ham radio operator, coming through the speaker of their console set. But this article, in the April 13, 1940, issue of Radio Guide reminds listeners that that fool kid was a member of an “old and honorable clan–a clan which, out of its own altruism and persistence, has helped give us the wonderful marvels of radio which today we take so much for granted.”

The article highlighted both the technical tinkering and “ragchewing” done by hams, who, according to the article, averaged 27 years of age.

The article starts with a story that is familiar, but I suspect at least partly apocryphal. A ham in Alaska was working a ham in New Zealand. The ham in Alaska gave a report of 549x. But suddenly, the “sharp dots and dashes faltered, once, twice, then pieced out falteringly. ‘I feel ill ….” Suddenly, the radio went silent.

The ham in New Zealand put out a distress call, and eventually raised a station on the West Coast of the U.S. He put out a call for Alaska, and soon raised another station in the Alaskan ham’s hometown. That ham raced to the house, dragged the unconscious ham outside from the home where he had been suffering from carbon monoxide poisoning.

No names were given, and the story is almost identical to the one given in the 1939 film Radio Hams, which appears at the bottom of this page. The story recounted in the film took place “some years ago,” and similarly contains few details. It does mention the name of the ham, Clyde De Vinna, and there seems to be some corroboration on his Wikipedia entry, although few details of the incident.

The article does identify another ham, Frank Carter, W2AZ, of East Rockaway, Long Island, who maintained daily contact with the Archbold Expedition in New Guinea. Other stations involved in that communication were K4FAY in Puerto Rico, W6LYY, W4DLH, and K6OQE in Hawaii. The magazine recounted a story of W2AZ getting an urgent call from a station in Colobmia looking for information on his children who were ill in a New York hospital.

Shown here operating an RCA recorder is Father Bernard R. Hubbard, “the Glacier Priest.” Hubbard was an American Jesuit Priest, ordained in Austria in 1923. Upon his return to America, he was a college lecturer in German, geology, and theology. He found, however, that his heart wasn’t completely in academia. He therefore undertook regular expeditions to Alaska to study geology and volcanology. By the late 1930s however, his interests turned to anthropology, and he began to study the culture and language of native Alaskans.

Shown here operating an RCA recorder is Father Bernard R. Hubbard, “the Glacier Priest.” Hubbard was an American Jesuit Priest, ordained in Austria in 1923. Upon his return to America, he was a college lecturer in German, geology, and theology. He found, however, that his heart wasn’t completely in academia. He therefore undertook regular expeditions to Alaska to study geology and volcanology. By the late 1930s however, his interests turned to anthropology, and he began to study the culture and language of native Alaskans.

He was a compelling lecturer, and at one point was the world’s highest paid member of the lecture circuit, earning up to $2000 per talk. He donated the money to Jesuit missions in Alaska.

He’s shown here on the cover of National Radio News, April-May 1940, recording chants by these native Alaskans.

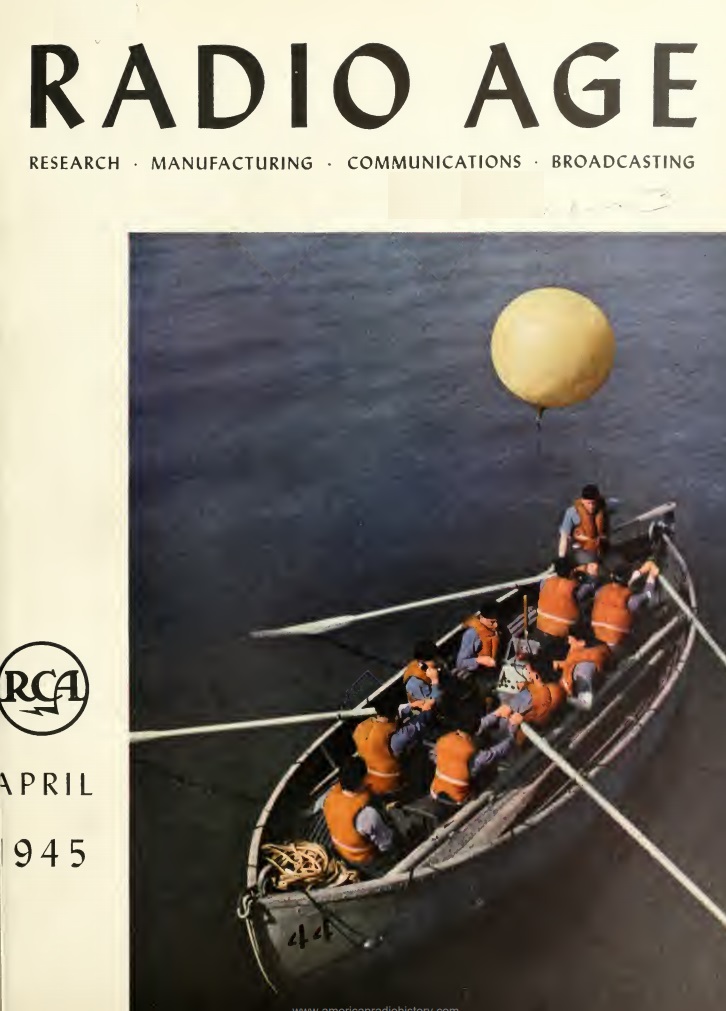

We previously featured the Radiomarine Corporation of America’s model ET-8030 lifeboat radio. While the set was never deployed during the war, it was featured in the April 1945 issue of Radio Age, a quarterly magazine published by RCA. It is featured on the cover of the magazine, being operated by cadets at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, Kings Point, N.Y..

We previously featured the Radiomarine Corporation of America’s model ET-8030 lifeboat radio. While the set was never deployed during the war, it was featured in the April 1945 issue of Radio Age, a quarterly magazine published by RCA. It is featured on the cover of the magazine, being operated by cadets at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, Kings Point, N.Y..

The set, permanently mounted in the lifeboat, operated with a hand crank which provided the power and keyed the transmitter. In the automatic mode, the set would send a long dash and SOS on 500 kHz and 8280 kHz. It could also be switched into the manual mode, which allowed voice transmission, and included a receiver for both 500 kHz and 8100-8600 kHz. The set could be used with an inveted vee antenna mounted to the boat’s mast, but the most prominent feature was a helium balloon which could hoist the antenna to height of 300 feet and keep it there for a week. As a backup, a box kite was also provided.

The set, permanently mounted in the lifeboat, operated with a hand crank which provided the power and keyed the transmitter. In the automatic mode, the set would send a long dash and SOS on 500 kHz and 8280 kHz. It could also be switched into the manual mode, which allowed voice transmission, and included a receiver for both 500 kHz and 8100-8600 kHz. The set could be used with an inveted vee antenna mounted to the boat’s mast, but the most prominent feature was a helium balloon which could hoist the antenna to height of 300 feet and keep it there for a week. As a backup, a box kite was also provided.

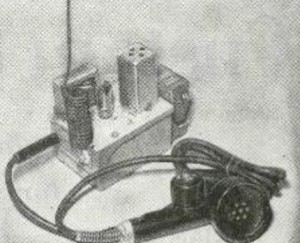

The April 1950 issue of Radio Electronics carried the plans for this one-tube home broadcaster, dubbed the “Carry-Talkly” by author Otto Wooley, W0SGG. The microphone and chassis were easily sourced, since they were both war surplus, a Signal Corps BC-1366 jack box, and the T-17 microphone. The circuit used a 1R5 tube, and an 18-24 inch antenna provided a good signal around the house.

The April 1950 issue of Radio Electronics carried the plans for this one-tube home broadcaster, dubbed the “Carry-Talkly” by author Otto Wooley, W0SGG. The microphone and chassis were easily sourced, since they were both war surplus, a Signal Corps BC-1366 jack box, and the T-17 microphone. The circuit used a 1R5 tube, and an 18-24 inch antenna provided a good signal around the house.

The author’s set was tuned to 550 kHz, although he pointed out that on a receiver with a high-gain IF stage, the broadcaster could be tuned to the intermediate frequency and be picked up regardless of the receiver’s dial position.

These ads appeared a hundred years ago in the May 1920 issue of Electrical Experimenter. The one that caught my eye was the ad for the Rogers Bros. safety razor, using Gillette blades, from the D.A.R. Sales Company of 2521 17th Avenue South, Minneapolis.

These ads appeared a hundred years ago in the May 1920 issue of Electrical Experimenter. The one that caught my eye was the ad for the Rogers Bros. safety razor, using Gillette blades, from the D.A.R. Sales Company of 2521 17th Avenue South, Minneapolis.

The 1920 Minneapolis City Directory shows no company by that name. However, the current building at that address, a small apartment building, was built in 1917. In 1920, it was the residence of one Freeman T. Rogers, a clerk with Northwest Marble & Tile Co. Since he has the same surname as the razor, I assume he was the proprietor. Two other men, Arthur J. Nordstrom, employed as an estimator by Janney Semple Hill & Co., and David M Burns, a laborer, are also listed as residing at that address.

Rogers, born about 1895, is listed in the 1940 census, still living in South Minneapolis. This would have made him about 25 years old at the time of his entrepreneurial venture into the home-based razor business. I wonder if his bosses at the marble company knew if he was moonlighting.

For others looking for a business to get into, the battery charging business couldn’t be beat, as shown by the second ad.

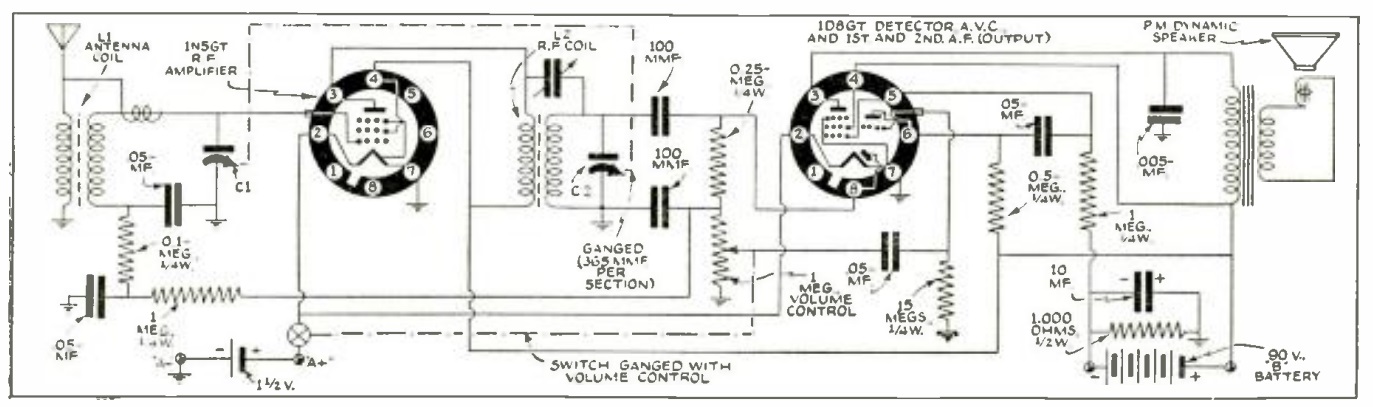

Roger Dickey of Grand Prairie, Texas, had been a radio serviceman since 1933, and had frequent requests from local farmers for a small economical battery operated radio. Even though the farms weren’t electrified, there were a number of strong local stations, including 50,000 watt WFAA only about 10 miles away. The expensive commercial sets on the market were overkill, and Dickey set out to come up with a better set suited to local needs.

Roger Dickey of Grand Prairie, Texas, had been a radio serviceman since 1933, and had frequent requests from local farmers for a small economical battery operated radio. Even though the farms weren’t electrified, there were a number of strong local stations, including 50,000 watt WFAA only about 10 miles away. The expensive commercial sets on the market were overkill, and Dickey set out to come up with a better set suited to local needs.

He did so with the two-tube TRF set shown here, which he said performed about as well as a superheterodyne. The set used a 1N5GT as RF amplifier, with a dual tube, a 1D8GT serving as detector, and first and second AF stages. A short antenna pulled in all of the local stations during the day. At night, with the longer antenna, the set pulled in WGN and WMAQ from Chicago, WLW Cincinnati, and WSM Nashville, without any overload from the 50,000 watt station just ten miles down the road.

The design was featured in the April 1940 issue of Radio Craft magazine.