For your listening pleasure, here’s what you would have heard on the radio 75 years ago tonight, New Year’s Eve 1944, the Jack Benny show:

For your listening pleasure, here’s what you would have heard on the radio 75 years ago tonight, New Year’s Eve 1944, the Jack Benny show:

Forty years ago this month, the December 1979 issue of Popular Mechanics shows this idea, a version of which comes up every few decades: A bridge connecting Eurasia and America across the Bering Strait.

Forty years ago this month, the December 1979 issue of Popular Mechanics shows this idea, a version of which comes up every few decades: A bridge connecting Eurasia and America across the Bering Strait.

This design was by California engineer T.Y. Lin and was dubbed the Peace Bridge. It was designed for highway traffic and featured smoothly curved piers to deflect upward advance ice floes. The average water depth over the proposed route was a modest 150 feet, making the project somewhat feasible. This design used 1000 foot prefabricated sections that would be brought to the site by barge.

Lin set the price tag for the bridge at about $3 billion, which he noted was a drop in the bucket compared to the cost of the arms race.

This week, we were visiting Matamoros, Mexico, which is the border city adjacent to Brownsville, Texas. When driving across the international bridge, one of the first sights is a fairly large encampment of refugees from Central America. Most are from El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua, but there are exceptions. Inexplicably for people who ostensibly came on foot, some are reportedly from Cuba and even Africa. They came as part of the migrant caravans. The picture above shows part of the camp. (Click on any of the images for a larger version.)

This week, we were visiting Matamoros, Mexico, which is the border city adjacent to Brownsville, Texas. When driving across the international bridge, one of the first sights is a fairly large encampment of refugees from Central America. Most are from El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua, but there are exceptions. Inexplicably for people who ostensibly came on foot, some are reportedly from Cuba and even Africa. They came as part of the migrant caravans. The picture above shows part of the camp. (Click on any of the images for a larger version.)

These persons are living in small tents, all set up in the border zone under the control of the Mexican federal government (indicated by “Zona Federal” on the sign in the bottom picture). A few yards further south, the area is under the jurisdiction of the State of Tamaulipas, and the state authorities do not allow them to make camp there. The camp is orderly, and there is a strong armed military presence. A hundred yards to the north is the United States. I should note that the fence is pre-existing, and is not there to keep the people inside. The area is open on other sides. This picture is taken on the sidewalk leading to the international bridge, and the fence is there to serve as a barrier between the line leading to the bridge, and the rest of the town.

These persons are living in small tents, all set up in the border zone under the control of the Mexican federal government (indicated by “Zona Federal” on the sign in the bottom picture). A few yards further south, the area is under the jurisdiction of the State of Tamaulipas, and the state authorities do not allow them to make camp there. The camp is orderly, and there is a strong armed military presence. A hundred yards to the north is the United States. I should note that the fence is pre-existing, and is not there to keep the people inside. The area is open on other sides. This picture is taken on the sidewalk leading to the international bridge, and the fence is there to serve as a barrier between the line leading to the bridge, and the rest of the town.

I asked around whether it would be a good idea to speak with any of the refugees, and the consensus was that I shouldn’t. However, I’m not one to listen to consensus, and when the opportunity presented itself, I took advantage of it. Part of the camp is immediately adjacent to the sidewalk leading to the international bridge, and we were only feet away from people on the other side of a fence.

I had the opportunity to speak with a woman named Sandra, who told me that she had come from El Salvador. She has two daughters with her, 11 and 7 years old. She also has an 18 year old daughter and an older son, both of whom are already in the U.S. She was living in one of the tents shown at the top of the page.

When I asked if they had walked all the way, she said they had, but there might have been a misunderstanding, because it sounded like she had rides for at least part of the way. But in any event, she had come a very long way, and I asked her why.

Her story sounded very compelling and very honest. She said that the government in El Salvador was unable or unwilling to protect its people from gang violence. When the government did try to crack down and imprison gang members, some of them infiltrated the elementary schools to recruit new members to replace them. When they asked, they wouldn’t take no for an answer. She told the story of one gang member who branded his own infant son with the gang’s symbol, to show that the gang would pass on to another generation.

The last straw for Sandra came as she was running her business, which sounded like selling something in the marketplace. One day, gang members came to her, shoved a gun in her side, and told her that she worked for them now, and that she would start handing over her profits. She feared for her life, so she said yes. But that night, she decided to sell all she owned and start heading for the United States. The same thing had happened to some of the daughter’s classmates. The children were told that they had to join the gang. Instead of doing so, they left on their own and headed north.

I did get the impression that she had been misled by someone to at least some extent. She told me that she was disappointed when she got here and not immediately allowed to enter the U.S., because someone told her that the “law had changed” from when she started until when she arrived at the border. She told me that before she left El Salvador, someone told her that she would “get right in” to the U.S. When she got here and that wasn’t the case, someone explained it away by saying that the law had changed.

I asked about conditions in the camp, and she didn’t seem to have complaints. I asked her if she had food and water. She told me she did, and even pointed out a 5-gallon bottle of drinking water inside her tent. It looked to be a commercial bottle of water of the type found in most Mexican homes. She didn’t mention what food she had, but she wasn’t complaining at all. She said that she had many donated goods such as food and blankets. She pointed to the wood fire that she used to cook. It looked to be made up of scavenged branches.

She specifically mentioned the military, and seemed genuinely thankful that the Mexican authorities were there providing protection. She was quite clear that she viewed the military presence as a positive. There was no hint that the heavily armed presence was there to keep her in. In this picture, you can see some of the military near the river. Most of the tents appeared to be up at street level, but people did go down to the river, presumably to wash (and likely, to go to the toilet, as I didn’t see any evidence of portable toilets in the actual encampment). The military presence (marines and sailors, I’m told) was there keeping a watchful eye. She said that she felt safer inside the camp, with the military presence, than she did outside.

She specifically mentioned the military, and seemed genuinely thankful that the Mexican authorities were there providing protection. She was quite clear that she viewed the military presence as a positive. There was no hint that the heavily armed presence was there to keep her in. In this picture, you can see some of the military near the river. Most of the tents appeared to be up at street level, but people did go down to the river, presumably to wash (and likely, to go to the toilet, as I didn’t see any evidence of portable toilets in the actual encampment). The military presence (marines and sailors, I’m told) was there keeping a watchful eye. She said that she felt safer inside the camp, with the military presence, than she did outside.

Sandra had even found work in Mexico, but I doubt if it paid particularly well. She and some of the other refugees had been recruited to hand out flyers for TelCel, a Mexican cellular provider. It sounded like this was just a one-time opportunity, but she was at least able to earn a few pesos. And it shows that even though she had to make her residence in the federal border

zone, she was able to move about the city freely.

She had already had one appointment with U.S. immigration, and had another scheduled in about six weeks. At some point, she was given a list of lawyers, but so far, she hasn’t found one who would take her case. I asked her what Americans could do if they wanted to help. She didn’t ask for anything. She was quite adamant that her material needs were being met, and she seemed grateful as she pointed to the donated items in her tent. But she did start to cry, and told me that she just wanted a safe place for herself and her children, and to be reunited with the older children who were already in the U.S.

I asked Sandra if I could take her picture, and as I suspected she would, she said no, because she was afraid. When I first introduced myself, she had told me her last name, but I told her I wouldn’t use it. I gave her my card, and pointed out the address of this website where her story would appear. I also pointed out that I’m a lawyer, but not an immigration lawyer, and not in Texas, so I wasn’t in a position to provide much practical help. My wife (who was serving as my interpreter) and I both asked God to bless her before we went our way. After I left, I wondered if I should have given her something, perhaps a treat for her children. But she wasn’t asking for anything like that–she was asking only for safety, something I didn’t have to offer.

I still have little doubt that Sandra and her children are pawns in someone else’s political game. But I also have absolutely no doubt of her sincerity, and that she is fleeing an impossible situation of lawlessness in El Salvador. It seemed clear to me that she has a well-founded fear of

persecution there, and I hope whoever is assigned to hear her case sees it the same way.

The residents of Matamoros with whom I spoke were generally sympathetic, but did have a somewhat different perspective. From them, I learned that of those who originally arrived in these caravans, about 80% have returned home. It seems apparent to me, and to those I talked to, that most of these people were themselves victims. They were victims of people who, for whatever political motivation, made promises that they knew they wouldn’t be able to keep. Eventually, it dawned on most of the people waiting at the border that they were victims. They presented themselves to the Mexican government, and were given a bus ticket back to the border with Guatemala.

Most of those like Sandra who remain at the border–about a fifth of the original number–already have appointments with U.S. Immigration for an asylum interview, and they are waiting to take their chances and plead their case.

Many Mexicans have strong feelings on the subject. There’s a certain amount of anger based upon reports–all secondhand, I should add–that assistance has been rejected by the members of the original caravan. Not only in Matamoros, but as the caravan passed through Mexico, Mexicans were generous, and offered food and other supplies. In many cases, these were personal gifts from residents who were sharing the food from their own table. There are stories that this aid was rejected as not being good enough. Naturally, after this happens a few times, the presence of the newcomers is resented. (I should add that Sandra seemed genuinely grateful for the donated goods she had received.) Mexicans also point out that the caravans entered Mexico illegally, and that their continued presence is in violation of Mexican law.

There’s also a sense that the caravan is there for the specific intent of destabilizing Mexico, the United States, and Canada. The reports of gifts being rejected seem to have certainly fed this sense.

I think it’s an important distinction that many, but not all, of the migrants have returned home. They got to the border, and it was soon apparent that they weren’t going to get easy entry. At best, they would need to stay at an austere camp within sight of the border. It seems reasonable that if someone had only a tenuous claim on asylum, that it would make sense to turn around and head home. On the other hand, if one truly had a valid claim of fear of persecution, then it would make perfect sense to remain–even in poor conditions–until their case is heard. Sandra’s story sounded credible to me. And one of the things that made it credible was the fact that she was willing to live in a tiny tent until she had an opportunity to present her case.

Also, as far as I can tell, Sandra has violated no law. She seeks to become a legal immigrant to the U.S., based upon a claim of asylum. As far as I can tell, she scrupulously complied with U.S. law–she presented herself to the authorities at the border and told them why she was there. They set an appointment for her, and told her that she would need to wait outside the United States. That’s exactly what she did, and then she showed up for her appointment as scheduled. She was told to go back and wait for her next appointment, and that’s exactly what she did. And she gave me every indication that she was grateful for the opportunity.

Under U.S. law, a person is entitled to asylum if they have a credible claim of persecution. I have no doubt that this is true for Sandra, and I have no doubt that she will be given a fair hearing to prove her case. Eighty percent of the refugees apparently went home after learning how the system worked. She did not, and that adds to the credibility of her case.

I asked residents of Matamoros what Americans can do to help. We don’t want to encourage the opportunists who convinced people to make a dangerous journey. But on the other hand, the people who remain need help to meet their basic needs.

The consensus is that the local Roman Catholic churches–in both the United States and Mexico–are doing the best to meet this need. This article (in Spanish) describes part of that relief effort, a joint effort between the two neighboring dioceses. Interestingly, the Mormon Church also got high marks for the humanitarian services it provides to refugees, as shown by this article about the cooperation between the two denominations.

If you would like to donate, one charity that is making a very real difference in the lives of these refugees is Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley, who are spearheading efforts on the U.S. side of the border. You can make a monetary donation by clicking on this link. If you want to donate needed supplies, they have a wish list on Amazon, and orders will be shipped directly to them. When ready to purchase items on their list, please select the “Humanitarian Respite Center (In-Kind)” address listed for the shipping. As Sandra made clear, at this point, there’s not a pressing need for material goods on the southern side of the border. Catholic Charities is busy processing those whose applications were approved, and donations are needed at their respite center on the northern side of the border.

The same Savior after whom Sandra’s country is named said, “I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in.”

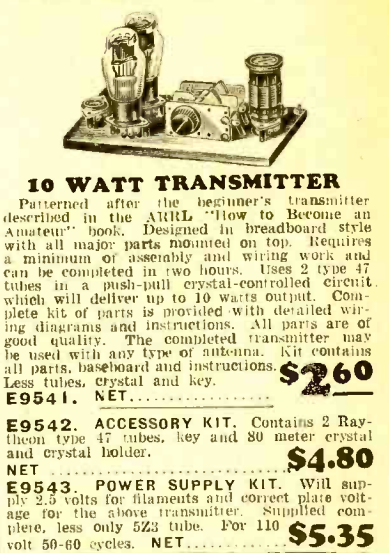

Eighty years ago, the newcomer to amateur radio could get on the air with this transmitter kit from the 1939 Allied catalog. It was patterned after the transmitter shown in the ARRL publication How to Become a Radio Amateur, and used two type 47 tubes running push-pull. The set could be put together in about two hours, and would put out up to 10 watts on 80 meters.

Eighty years ago, the newcomer to amateur radio could get on the air with this transmitter kit from the 1939 Allied catalog. It was patterned after the transmitter shown in the ARRL publication How to Become a Radio Amateur, and used two type 47 tubes running push-pull. The set could be put together in about two hours, and would put out up to 10 watts on 80 meters.

The cost of the kit itself was $2.60, but it wasn’t quite ready to go. The accessory kit included the  two tubes, a crystal, and key. If the beginner was lacking all of those items, that would be an additional $4.80. If the new ham already had a commercial receiver, then he could probably tap into the power supply to run the transmitter. Otherwise, the power supply would be an additional $5.35, for a grand total of $12.75.

two tubes, a crystal, and key. If the beginner was lacking all of those items, that would be an additional $4.80. If the new ham already had a commercial receiver, then he could probably tap into the power supply to run the transmitter. Otherwise, the power supply would be an additional $5.35, for a grand total of $12.75.

If he didn’t have a receiver already, then the bare minimum would be the kit shown here on the same page. The kit, using a single type 30 tube, cost $4.45. The tube and battery would be an additional $1.75. The coils that came with the radio covered the broadcast band, so getting on the ham bands would also require the shortwave coils, for 85 cents.

This photo from the collection of the Imperial War Museum was taken 75 years ago today, Christmas 1944, and bears the following description:

This photo from the collection of the Imperial War Museum was taken 75 years ago today, Christmas 1944, and bears the following description:

In the living room of their home at 28 Marsworth Avenue, Pinner, Mrs Devereux and her daughter Jean enjoy a Christmas tea party, with four of Jean’s friends. The table is laden with sandwiches and mince pies. In the background, the Christmas tree which is a gift from her father, serving in Italy, can be seen. The tree was purchased through the ‘Gifts to Home League’ of the YMCA. A portrait of Trooper Devereux is just visible decorating one of the branches, near to the top of the tree.

In the photo below, twelve-year-old Jean cuts the cake.

Merry Christmas from OneTubeRadio.com!

Merry Christmas from OneTubeRadio.com!This photo establishes conclusively that Santa Claus has been placing radios under the tree for a full century, since the photo was taken on Christmas, 1919.

Shown is the family of U.S. Secretary of War Newton Baker. From left to right are his daughter Betty (Elizabeth Baker McGean), son Jack (Newton D. Baker, III), daughter Peggy (Mrs. Fulton Wright), and wife Elizabeth. The younger children were obviously extra good that year, since Peggy is shown playing her Schroeder-style toy piano, and was probably also the recipient of the doll bed shown in the background.

But young Master Jack had obviously been very deserving, since Santa brought him a radio! Not only was he probably the first on his block (child or adult) to have a radio, it was probably one of the first ever received as a Christmas present. The wartime ban on private radio receivers (presumably ordered by his father) had only ended on April 15 of that year. (The transmitting ban ended on October 1.)

But young Master Jack had obviously been very deserving, since Santa brought him a radio! Not only was he probably the first on his block (child or adult) to have a radio, it was probably one of the first ever received as a Christmas present. The wartime ban on private radio receivers (presumably ordered by his father) had only ended on April 15 of that year. (The transmitting ban ended on October 1.)

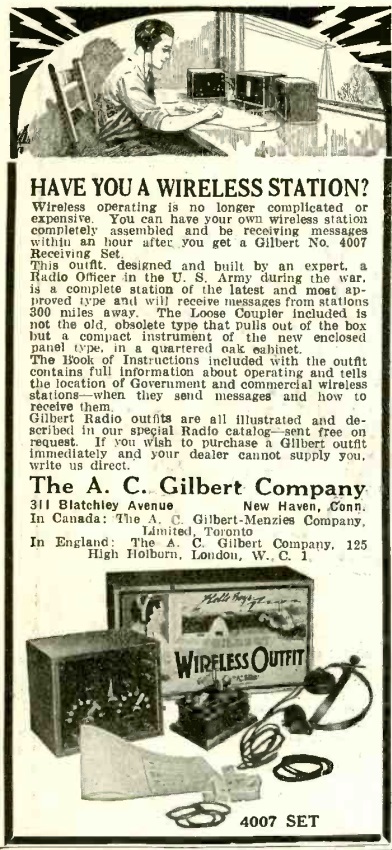

The site from which this picture is taken, Shorpy.com (see more information below) has a high-resolution copy,which allows more detail of the radio to be seen. Unfortunately, there’s not enough to be able to positively identify the set, but it does appear to be a fairly high-end crystal  set, not unlike the A.C. Gilbert model 4007 shown at the right (from the January, 1920, issue of Electrical Experimenter). According to another ad for that set, the list price was $25, and it was said to have a range of 200 miles. The one in the picture looks comparable. Since Master Jack lived right in Washington, he certainly would have been able to pull in the strong signals of station NAA in Arlington. Of course, any voice modulation was extremely rare at that time, so he would need to sit down and teach himself the code. And he wouldn’t hear anything with the set under the tree, since it doesn’t appear to be hooked up to antenna and ground. But since he was right in Washington, only a modest antenna would have been required to pull in the powerful government station. So I suspect he was hearing sounds out of the headphones Christmas night.

set, not unlike the A.C. Gilbert model 4007 shown at the right (from the January, 1920, issue of Electrical Experimenter). According to another ad for that set, the list price was $25, and it was said to have a range of 200 miles. The one in the picture looks comparable. Since Master Jack lived right in Washington, he certainly would have been able to pull in the strong signals of station NAA in Arlington. Of course, any voice modulation was extremely rare at that time, so he would need to sit down and teach himself the code. And he wouldn’t hear anything with the set under the tree, since it doesn’t appear to be hooked up to antenna and ground. But since he was right in Washington, only a modest antenna would have been required to pull in the powerful government station. So I suspect he was hearing sounds out of the headphones Christmas night.

The image above is courtesy of Shorpy, an amazing archive of thousands of historical American photographs from the 1850s to the 1950s. The Washington Post describes the site as one which offers a chance to time travel. We hope the same can be said about OneTubeRadio.com. As you celebrate Christmas today, enjoy this opportunity to visit a young radio listener a century ago. If you gaze closely enough at the photo, perhaps you’ll be able to hear the buzz of NAA’s arc coming through those headphones.

Eighty years ago tonight, Christmas Eve 1939, these French soldiers attended midnight mass on the Maginot Line.

On this Christmas Eve, remember the American soldiers and Belgian sailors lost in the sinking of the SS Léopoldville, a Belgian ship chartered by the British Admiralty to transport American soldiers to fight in the Battle of the Bulge. The ship sailed from Southampton across the English Channel to Cherbourg. About five miles from its destination, the ship was torpedoed by a German U-boat. About a hundred men were killed instantly.

On this Christmas Eve, remember the American soldiers and Belgian sailors lost in the sinking of the SS Léopoldville, a Belgian ship chartered by the British Admiralty to transport American soldiers to fight in the Battle of the Bulge. The ship sailed from Southampton across the English Channel to Cherbourg. About five miles from its destination, the ship was torpedoed by a German U-boat. About a hundred men were killed instantly.

The captain and crew spoke no English, and the American soldiers didn’t understand the abandon ship instructions given in Flemish. Some soldiers boarded lifeboats, but many did not realize that the ship was sinking. Various errors prevented other vessels from being notified, and many went down with the ship or succumbed to hypothermia in the icy waters of the Channel. Approximately 763 American soldiers, as well as 56 members of the crew, died.

The military kept the details of the incident a secret, and discharged soldiers were even told that they couldn’t speak of the incident lest they lose their GI benefits. Documents regarding the incident remained classified until 1996.

References

Shown here are the televisions that were available 70 years ago from the Belmont Radio Corporation, 5927 West Dickens Avenue, Chicago.

Shown here are the televisions that were available 70 years ago from the Belmont Radio Corporation, 5927 West Dickens Avenue, Chicago.

The ad featured two sets. “The Criterion”, a console set, had a list price of $349.95. “The Challenger”, a table set, sold for $299.95. Both were billed as having a 176 square inch picture. This was apparently before the days when TV manufacturers started measuring the picture diagonally. 176 square inches would be equivalent to about a 19 inch diagonal tube. Other sets in the Belmont line went as small as 74 square inches, or about 12 inches diagonally.

The ad appeared in the December 1949 issue of Radio Retailing.

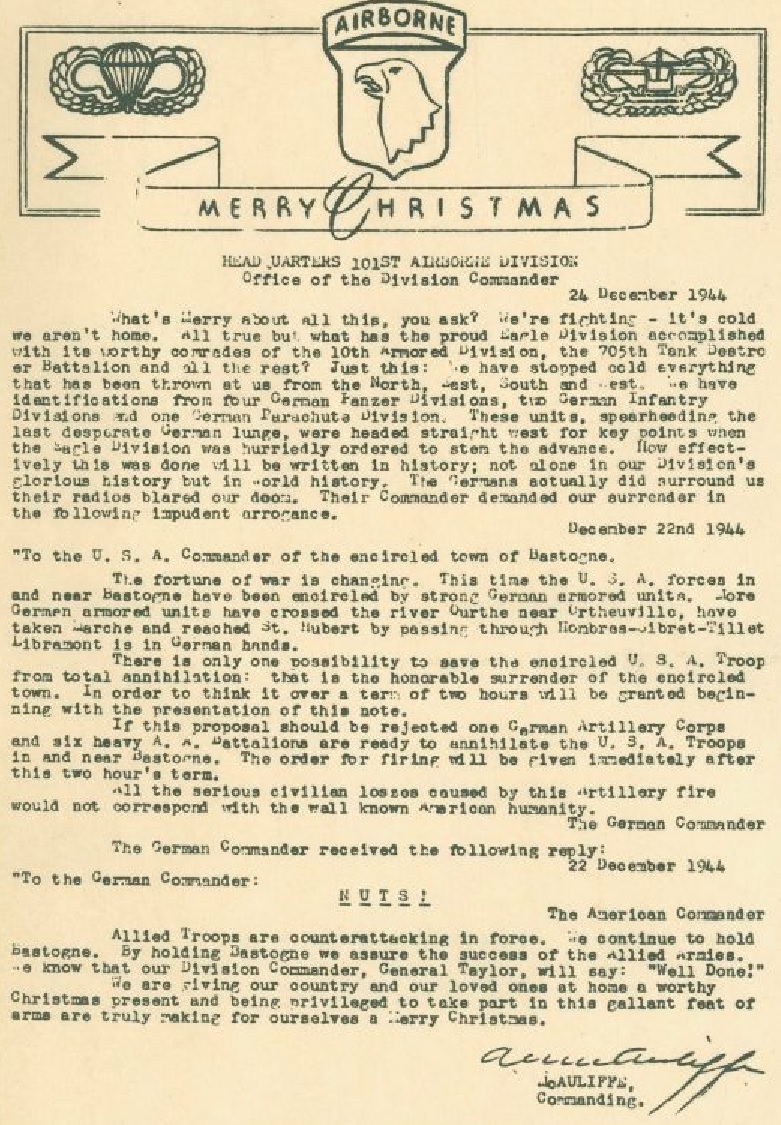

75 years ago today, during the Battle of the Bulge, four German soldiers, two officers and two enlisted men approached the American lines waving white flags. They had a message for the American commander. They were blindfolded and led to headquarters in the encircled town of Bastogne, Belgium, where they delivered the following message for Brig. Gen. Anthony C. McAuliffe:

75 years ago today, during the Battle of the Bulge, four German soldiers, two officers and two enlisted men approached the American lines waving white flags. They had a message for the American commander. They were blindfolded and led to headquarters in the encircled town of Bastogne, Belgium, where they delivered the following message for Brig. Gen. Anthony C. McAuliffe:

December 22nd 1944

To the U.S.A. Commander of the encircled town of Bastogne.

The fortune of war is changing. This time the U.S.A. forces in and near Bastogne have been encircled by strong German armored units. More German armored units have crossed

the river Ourthe near Ortheuville, have taken Marche and reached St. Hubert by passing through Hompre-Sibret-Tillet. Libramont is in German hands.There is only one possibility to save the encircled U.S.A troops from total annihilation: that is the honorable surrender of the encircled town. In order to think it over a term of two hours will be granted beginning with the presentation of this note.

If this proposal should be rejected one German Artillery Corps and six heavy A. A. Battalions are ready to annihilate the U.S.A. troops in and near Bastogne. The order for firing will be given immediately after this two hours’ term.

All the serious civilian losses caused by this artillery fire would not correspond with the well known American humanity.

The German Commander.

The general, still half asleep, said “Nuts!” as he climbed out of his sleeping bag.

Since a written message was received, it was only fitting to deliver a written reply. After some consultation as to the exact language, someone suggested that the general’s initial response was the best. A typist was summoned, and the following reply was made:

December 22, 1944

To the German Commander,

N U T S !

The American Commander

It was explained to the German officers that the message essentially meant, “Go to hell,” and the Germans communicated this to their commander.

In his Christmas message to his troops, the general included the exchange, as shown above. As  we saw in a previous post, even though the town was cut off, it had a reliable VHF communications link, and supplies were being air dropped. And there was even a mimeograph machine which could be used for a Christmas message. If the German commander had known these things, it’s doubtful that he would have expected a surrender.

we saw in a previous post, even though the town was cut off, it had a reliable VHF communications link, and supplies were being air dropped. And there was even a mimeograph machine which could be used for a Christmas message. If the German commander had known these things, it’s doubtful that he would have expected a surrender.

References