Today marks the 75th anniversary of D-Day, June 6, 1944, the beginning of the Allied invasion of Europe during World War II. On the day of the invasion, 4414 Allied servicemen were confirmed dead. Germans suffered between 4000 and 9000 casualties.

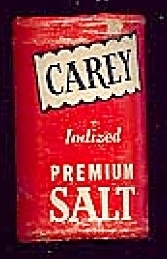

When I think of D-Day, my first thought is of a little salt container like the one shown here.

When I think of D-Day, my first thought is of a little salt container like the one shown here.

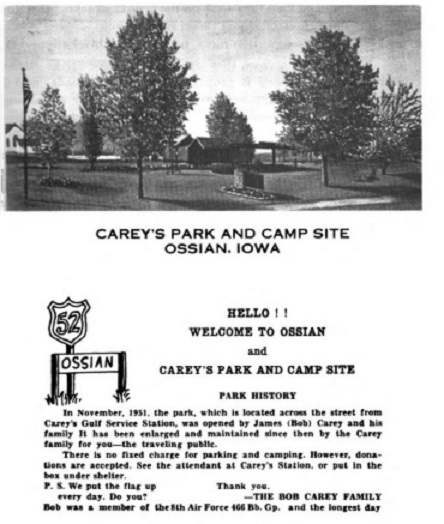

Some time in the late 1960s or early 1970s, my family and I were coming home from somewhere and were passing through Ossian, Iowa, where we stopped for a picnic lunch at a small park across the highway from a gas station.

As we were getting set up, a gregarious gentleman came over and told us that he just got a call that we had forgotten the salt, so he was giving us the container shown here. He was the owner of the gas station, and it turns out that his name was Carey. He handed out little shakers of Carey salt as his business card. I guess it worked, since I remembered his name almost fifty years later.

His full name was James R. “Bob” Carey, Jr. Or more specifically, he was Sgt. Carey. He proudly let us know that he had served at D-Day, and to make sure there was no question about it, he pulled out a copy of The Longest Day and showed us his name as one of the servicemen interviewed by the author.

Sure enough, on page 285 of the book, his name is still there:

“Carey, James R. Jr., Sgt. [8th AF] Carey’s West Side Service, Ossian, Iowa.”

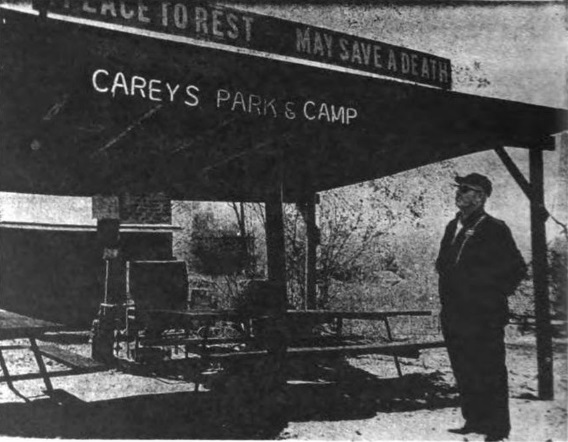

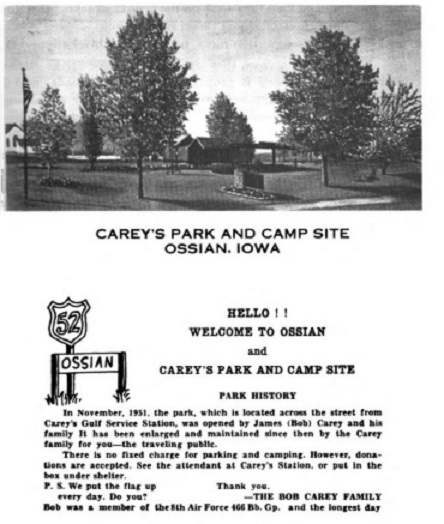

The park where we were picnicking was built by Carey at his own expense as his way of showing gratitude. It later became a city park. Carey described the park in 1972, probably about the same time we had passed through Ossian:

My name is James R. Carey. I own and operate a service station on U.S. 52 at Ossian, Iowa. I moved there in 1951.

Some time between 1945 and 1947 the highway commission relocated a short piece of U.S. 52 outside Ossian, and by doing this left a small piece of land on the south side of the highway in the shape of a piece of pie. When I moved into my station on the opposite side of the road, this piece of land was full of weeds and stumps and high grass. There were two holes, probably wells or old cisterns, which were mostly hidden and dangerous for children to play there.

This was an eyesore, and so I started to clean it up a little at a time when I could do it, and my family helped. First we mowed a strip along the highway, and then we mowed the whole thing; then we filled in the holes and did some more leveling, and started to take care of the trees. Then we discovered that people who stopped at our service station seemed to like to go over into this little piece of ground to have a picnic, or maybe just to stretch and relax a while before going on again. It cost us some money and time to do this, and nobody paid us for it; but we felt repaid by the nice things that people said about it when they stopped there. It meant something to have people say these things, and to see that the) really enjoyed stopping there.

Looking back over some 20 years now, we feel we’ve been repaid many times over for our efforts because this project has brought us together with our neighbors in doing something together that gave us all satisfaction. Some helped with the maintenance of the park: others contributed a tree or a shrub. I recall a man 10 miles away gave us a tree, and we went over and hauled it to the park in our truck.

We built a little shelter for the picnic tables. Then I thought we should put in a gas stove. I had the stove, and my neighbor Vern Meyer said he would donate the pipes and labor. And he did. Another neighbor, Elmer Rosa, said, “I’ll give you the roof boards for the shelter.” There was about $100 worth of roofboards and poles and rafters. The Fort Atkinson Nursery donated a flowering crab tree, and we put in flood lights to light it up in the spring when the blossoms came out. Then one day Fred Doan said we ought to have a little neon sign on the shelter. I said I couldn’t afford one. and he said, “I’ll donate it.” And he did. So we had a sign on the shelter that said “Careys Park & Camp.” We keep that sign on day and night.

The town of Ossian boundary line is just a few feet away from the camp, and we asked if they would put in a drinking fountain on the outside of the shelter. By that time we also had built another building for toilets, and we needed water for that. Everything in the park is open 24 hours a day.

I don’t remember anything in particular that Carey said about his service at D-Day. I only remember (and this is probably all he told us) that he was there and that he was proud of it. He did his part to liberate Europe, and then he came home. He started a gas station and did his part to offer rest to weary American travelers.

Sgt. Carey, thanks for a place to rest; thanks for the salt; and thank you for liberating Europe. The world is better because of you.

For more information about Carey, see His Legend Lives On in Northeast Iowa. Carey died in 1977 at the age of 57 and is buried at St. Francis de Sales Cemetery, Winneshiek County, Iowa.

Please see our earlier posts regarding the D-Day invasion:

The first link contains links to the NBC and CBS broadcast days for June 6, and are well worth listening to.

The cover of National Radio News, the publication of the National Radio Institute home study school, for June-July 1944 shows the exterior of Meadwell’s Radio & Electirc, 110-3rd Ave. S., Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

The cover of National Radio News, the publication of the National Radio Institute home study school, for June-July 1944 shows the exterior of Meadwell’s Radio & Electirc, 110-3rd Ave. S., Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.