USMC photo, via Wikimedia Commons.

In what would be the final Fourth of July of the War, American Marines parade through Paris a hundred years ago today, July 4, 1918.

USMC photo, via Wikimedia Commons.

In what would be the final Fourth of July of the War, American Marines parade through Paris a hundred years ago today, July 4, 1918.

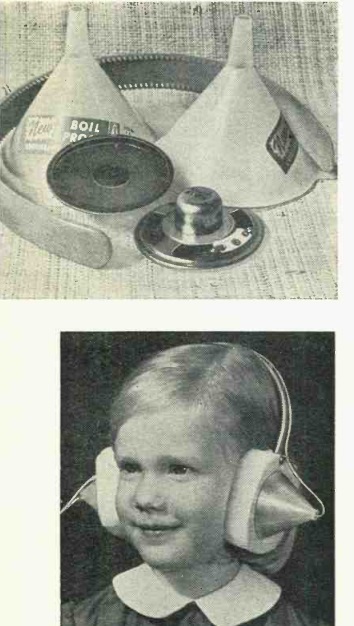

If you need a pair of stereo headphones today, you can go down to the local dollar store and get a fairly decent pair. But fifty years ago, if you wanted to save a little money, you could make your own pair, as shown here in the July 1968 issue of Popular Electronics.

If you need a pair of stereo headphones today, you can go down to the local dollar store and get a fairly decent pair. But fifty years ago, if you wanted to save a little money, you could make your own pair, as shown here in the July 1968 issue of Popular Electronics.

From the two pictures here, the construction details should be pretty obvious. Put the parts together, wire them up, put them on, and you have stereo headphones for what the magazine described as “99 cents per ear.”

For the aspiring mad scientist looking for a spectacular science project that combines fire, high voltage, and loud noise, the flame speaker described in the July-August 1968 issue of Elementary Electronics should fit the bill perfectly. We previously written about how a flame can serve as a radio detector. As this article shows, it can also serve as the speaker, as the flame can be induced to emit sound. Depending on how much work you want to do, the quality of the sound can be extremely good. But even a modest investment of time can make the flame produce sound, although the simpler setups will be somewhat distorted.

For the aspiring mad scientist looking for a spectacular science project that combines fire, high voltage, and loud noise, the flame speaker described in the July-August 1968 issue of Elementary Electronics should fit the bill perfectly. We previously written about how a flame can serve as a radio detector. As this article shows, it can also serve as the speaker, as the flame can be induced to emit sound. Depending on how much work you want to do, the quality of the sound can be extremely good. But even a modest investment of time can make the flame produce sound, although the simpler setups will be somewhat distorted.

The general principle is quite simple. The flame constitutes a plasma, often referred to as the fourth state of matter, made up of a cloud of positively charged atoms and free electrons. When an audio frequency signal is applied to the plasma, the positive ions and electrons move, creating a bending of the flame and room-filling sound.

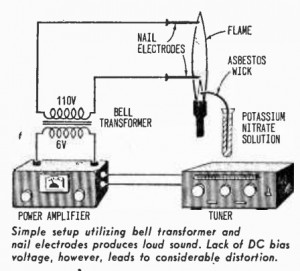

The simplest arrangement is shown here. The output of an audio amplifier is fed to a transformer to step up the voltage. Nearly any transformer can be used. In this case, a bell transformer–ordinarily used to step-down 120 volts to 6 volts–is hooked up in reverse. Such a transformer can be found inexpensively on Amazon, but it’s probably possible to scavenge one. A trip to the local thrift store will probably allow you to find a “wall wart” power supply. If you can find one with an output of about 6 volts ac, then your work is done. If you can only find one with a DC output, then you’ll need to open it up and remove the rectifier.

The simplest arrangement is shown here. The output of an audio amplifier is fed to a transformer to step up the voltage. Nearly any transformer can be used. In this case, a bell transformer–ordinarily used to step-down 120 volts to 6 volts–is hooked up in reverse. Such a transformer can be found inexpensively on Amazon, but it’s probably possible to scavenge one. A trip to the local thrift store will probably allow you to find a “wall wart” power supply. If you can find one with an output of about 6 volts ac, then your work is done. If you can only find one with a DC output, then you’ll need to open it up and remove the rectifier.

The transformer increases the voltage of the audio sufficiently to modulate the flame. This output is connected to two electrodes, in the form or ordinary nails, which are inserted into the flame.

The flame can come from a variety of sources. The higher the temperature the better, but the author was able to produce sound with as little as a single candle. Various types of torches, or even a bunsen burner, can also be used to produce more sound. An inexpensive butane torch would probably prove most adequate, or you can use an inexpensive propane torch such as the one shown here.

The ordinary combustion products do not provide sufficient plasma, so it is necessary to insert some potassium nitrate into the flame. The article recommends using an asbestos wick, in the form of “asbestos tape used to seal pipe joints in warm-air heating systems.” If you can’t find the potassium nitrate locally, it’s inexpensive on Amazon.

Of course, asbestos can’t be used today, since it would result in the haz-mat team immediately shutting down the science fair. But the article reveals that the potassium nitrate is in a solution of water, meaning that even a combustible wick would probably survive all but the hottest flames, at least long enough to do the experiment. So it seems that a normal wick, such as used in a kerosene lamp, would be more than adequate. Indeed, with some experimentation, it would seem that almost any kind of fabric could be used, as long as it begins the experiment saturated with water. Another option would be the use of welding fabric.

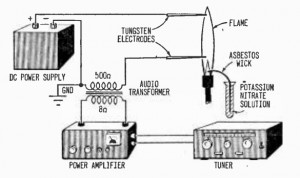

More advanced students will want to get rid of the distortion inherent in the simple design, and this can easily be done by providing a bias voltage. The article recommends about 400 volts. Other improvements include replacing the nails with tungsten or nichrome wire, and recommends sources. You can scavenge the nichrome wire from an old toaster, or buy it inexpensively on Amazon. The article recommends, of course, that proper precautions be taken if the high voltage bias is used. With the original simple setup, however, the experiment should be relatively safe, since no high DC voltages are used.

More advanced students will want to get rid of the distortion inherent in the simple design, and this can easily be done by providing a bias voltage. The article recommends about 400 volts. Other improvements include replacing the nails with tungsten or nichrome wire, and recommends sources. You can scavenge the nichrome wire from an old toaster, or buy it inexpensively on Amazon. The article recommends, of course, that proper precautions be taken if the high voltage bias is used. With the original simple setup, however, the experiment should be relatively safe, since no high DC voltages are used.

The original article is available from this link. Even the simplest version of this experiment is certain to take home a blue ribbon, and the more advanced version could produce truly spectacular results as the flame changes color and pulsates as it produces room-filling sound. The kid with the potato clock won’t stand a chance. You can derive some inspiration from this and other videos of flame speakers:

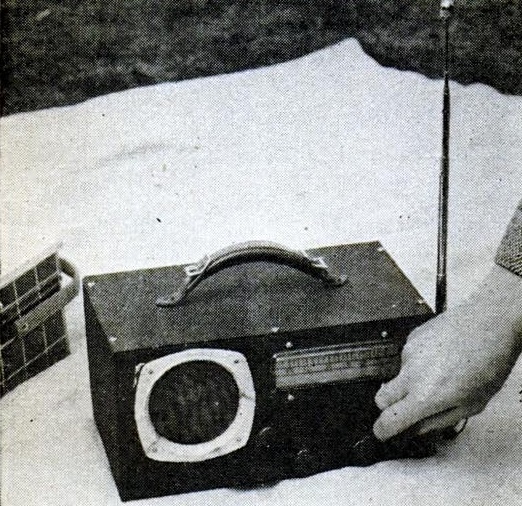

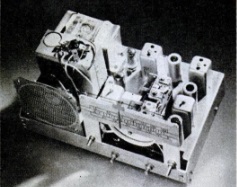

Seventy years ago this month, the July 1948 issue of Popular Science carried the plans for this ambitious project, a five-tube set which could be used either as a portable with an internal 6-volt storage battery, or mounted under the dash, as a car radio. On the go, it would be powered by the car battery and hooked to an external antenna. But at the flip of a switch, it could be unplugged and operated on its internal battery. In either configuration, it had a vibrator power supply inside.

Seventy years ago this month, the July 1948 issue of Popular Science carried the plans for this ambitious project, a five-tube set which could be used either as a portable with an internal 6-volt storage battery, or mounted under the dash, as a car radio. On the go, it would be powered by the car battery and hooked to an external antenna. But at the flip of a switch, it could be unplugged and operated on its internal battery. In either configuration, it had a vibrator power supply inside.

The internal battery could be charged from the car, or directly off AC  power. The AC charger consisted of only a selenium rectifier and a hefty “260 ohm 100 watt” resistor to drop the voltage.

power. The AC charger consisted of only a selenium rectifier and a hefty “260 ohm 100 watt” resistor to drop the voltage.

The set featured one stage of RF amplification in front of the converter for added sensitivity. Both the battery and vibrator were military surplus for high quality at a low cost.