This illustration appeared in Popular Mechanics a hundred years ago this month, September 1917, and illustrates a clever solution to a problem that no longer exists. It shows a simple way to convert a buzzer into a telegraph sounder.

This illustration appeared in Popular Mechanics a hundred years ago this month, September 1917, and illustrates a clever solution to a problem that no longer exists. It shows a simple way to convert a buzzer into a telegraph sounder.

At first blush, it seems rather obvious how to use a buzzer as a telegraph: Simply hook it up, as shown, in series with the key and the battery. If that’s how it were hooked up, that’s how I, or just about anyone who knows Morse Code these days, would be able to listen with ease.

It took me a few minutes to realize what was going on. This was a simple way to create a sounder that would sound like a landline telegraph. That kind of telegraph didn’t produce a continuous tone, as Morse Code does when sent by radio. Instead, it produces clicks and clacks as the arm of the sounder hits the coil. The landline telegrapher is listening for those clicks and clacks, the same way that I would be listening to the buzz of the buzzer. But the buzzing would be just as incomprehensible to the landline telegrapher, just as the clicks and clacks would be incomprehensible to me. The code being used is very similar (but not quite identical, since American telegraphers used American Morse, while radio operators use International Morse Code). But the medium being used is very different.

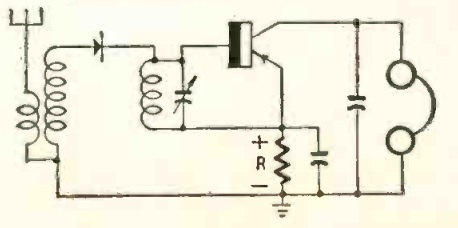

The secret of the diagram above is the wire run from point C to point F. Normally, a buzzer makes noise because the coil energizes and pulls the arm down. But in the process, it breaks the electrical contact between the arm and point C. This causes the coil to de-energize, and the arm swings back. When it gets back in position, the coil is powered up again, and the cycle repeats. This happens fast enough that a buzzing sound is produced.

In this diagram, the vibrator contact is shorted out. So when the arm is pulled toward the coil, it stays there until the key is released, just as would happen in a landline telegraph sounder. So instead of buzzing, the buzzer now clicks and clacks, and the aspiring landline telegrapher can use the modified buzzer to practice the trade.

According to the magazine, the idea was sent in by one Clarence F. Kramer of Lebanon, Indiana. Interestingly, Mr. Kramer apparently knew both versions of the code, since he was also a radio amateur. He is listed in the 1921-23 call books as being licensed as 9AOB, with an address of 414 E. Pearl St., Lebanon, Indiana. The April 1923 issue of Wireless Age shows that he pulled in, on a crystal set, 27 different broadcast stations, his best DX being 825 miles, WBAP in Ft. Worth, Texas. Another one of the stations he pulled in was WLAG in Minneapolis, the forerunner of WCCO. In the December 30, 1925 issue of the Indianapolis Star, he describes himself as an “ardent radio bug.”

He also appears to have been a Boy Scout, since one Clarence Kramer of Indiana, with various interests including wireless and telegraphy had a penpal request in the January 1915 issue of Boys’ Life magazine. While it could be another person with the same name, one Clarence F. Kramer was an engineer with Ford, holding a number of patents. If he went to work for Ford, then he is probably the Clarence Frank Kramer who died in Michigan in 1994 at the age of 92.