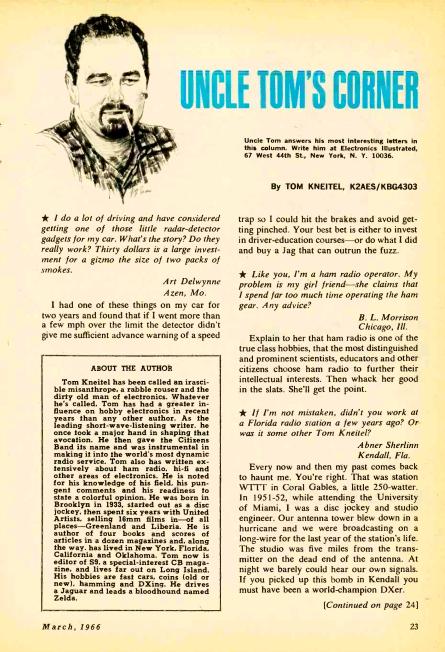

We’ve previously mentioned prolific radio author Tom Kneitel, best known by his 1960’s era call sign, K2AES. Starting 50 years ago this month with the March 1966 issue of Electronics Illustrated, Kneitel wrote the regular column Uncle Tom’s Corner, which he continued until the magazine’s demise in 1972.

His first column carried a sidebar with a biography, calling him an “irascible misanthrope, a rabble rouser and the dirty old man of electronics.” It noted that he was the leading writer on the subject of SWL’ing who later “gave the Citizens Band its name and was instrumental in making it into the world’s most dynamic radio service.”

According to the biography, Kneitel was born in Brooklyn in 1933 and got his start in electronics as a disc jockey. He later spent six years with United Artists, “selling 16mm films in–of all places–Greenland and Liberia.” In 1966, he had lived in New York, Florida, California, and Oklahoma. It noted that he drove a Jaguar and had a bloodhound named Zelda.

Kneitel had earlier held the calls K3FLL and WB2AAI. Prior to his death in 2008, he was W4XAA.

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

![]()