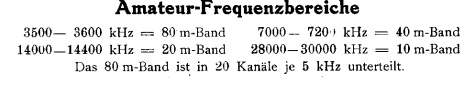

Chart showing German amateur frequency bands, 1944. DASD-CQ, September 1944.

It’s widely believed that amateur radio went off the air for the duration of World War II. That was certainly the case in the United States and Canada, as well as most of the warring countries. Some neutral countries remained on the air. For example, Portuguese hams remained on the air, and much of South America was still engaging in amateur radio as usual.

But strangely enough, the major exception was Nazi Germany. German stations were ordered off the air after commencement of hostilities in September 1939. But soon thereafter, many stations were granted a special wartime license, known as Kriegsfunkgenehmigung. QST for April 1940 carried the following announcement sent from Chris Schmelzer, D4BIU:

There seems to be a widespread misunderstanding concerning the activities of German amateur stations to-day. According to a statement made by our government, all sport activities, etc., will be continued during the war to as large an extent as possible. Due to this, amateur stations D4ACF, D4ADF, D4BIU, D4BUF, D4RGF, D4TRV, D4WYF, D4HCF and D4DKN have been relicensed recently. More licenses will follow shortly. The stations are supposed to carry on strictly in the usual manner.

The website of the Foundation for German communication and related technologies contains copies of many wartime issues of DASD-CQ, the journal of the German national amateur radio society, Deutschen Amateur-Sende-und Empfangs-Dienstes, which continued publication throughout the war. From recording calls contained in that journal, the author of the web page counts at least 86 active call signs through 1944. And DC5WW has provided a list (the source of which is not clear) of all licensed stations as of August 1944. These include a number of stations licensed only for 10 meters. And a collection of 1943 German QSL cards can be found at the website of Radioclub Braunschweig. In addition to the hams with transmitting licenses, a larger number of receiving licenses were issued to DASD members. It appears that the DASD was tasked with approving licenses at this time. A 1944 letter from DASD president Ernst Sachs to Heinrich Himmler explaining the importance of amateur radio is available online.

So it is clear that there were a significant number of hams on the air from Germany throughout the war. Many of them, it seems, were using a receiver very similar to the National HRO. In fact, the tuning condensers were manufactured by National and imported through Portugal. When the German military believed that they were not up to military specifications, they were given to the DASD for distribution to hams for use in receivers using German tubes.

As shown on the chart above, amateurs were allowed to operate on 20 channels between 3500 and 3600 kHz, as well as 7000-7200, 14000-14400, and 28000-30000 kHz. (Not surprisingly, the Germans called them kiloHertz rather than kilocycles at the time.)

One can only speculate as to why Nazi Germany allowed its hams to remain on the air when the free world was silent. The author of this page offers two reasons, both of which seem plausible. The first was to show the world a sense of normalcy. Apparently, the idea was for those in the rest of the world to have the impression that life was going on normally. Or, as the QST article above put it, “all sport activities, etc., will be continued during the war to as large an extent as possible.”

The other reason was more practical. It was believed that hams and SWL’s could provide valuable propagation information. Indeed, one source noted that both hams and SWL’s were required to keep duplicate logs and send one copy to the authorities for analysis.

According to that same author, there was apparently no political test for licensees. There was no special requirement of adherence to Nazi ideology (at least, no more so than required of the general population). While the original plan to issue licenses was apparently approved by the SS, the actual administration of the program was under the control of the Wehrmacht, whose concerns were presumably more practical than ideological.

Even more surprising is that there were a handful of QSO’s, during the war, between these German stations and British stations! In 1944, the British government allowed a small number of hand-selected prominent hams back on the air. Under this program, called “Plan Flypaper” the call signs G7FA through G7FJ were assigned and allowed to operate with 50 watts on 80, 40, 20, and 10 meters. Among these hams was Louis Varney, G5RV, who became G7FJ. The full details of this program, including the operating rules, can be found at the Southgate ARC website.

The participants in this program made numerous contacts with neutral countries, and a handful of contacts with German stations. They were forbidden from calling German stations, but they were instructed to make the contact if a German station called them. The purpose of this program was apparently two-fold. First of all, the idea was to simply make themselves available in case any interesting information was received. They had instructions, if an enemy station wished to send a message, to relay it to headquarters, and to inform the other station to contact them again the next day for any response.

The other idea was that if any Allied prisoners of war gained access to a transmitter, they would be able to make contact with one of these British stations. Apparently, neither of these goals was realized.

Here’s another interesting article about amateur radio in Nazi Germany, by Prof. Bruce Campbell KG4CUL: https://theconversation.com/nazis-pressed-ham-radio-hobbyists-to-serve-the-third-reich-but-surviving-came-at-a-price-90510

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

![]()