The wireless telegraph solved the Longitude Problem once and for all. Many maritime disasters over the centuries were the result of sailors not knowing their longitude. Determining latitude is relatively simple. From any position on earth, it is easy to determine the local time by observing the sun or stars. When the sun is at its highest point for the day, this is, by definition, noon local time. The sun’s altiude at that time can be used to quickly determine the observer’s latitude.

Longitude, however, was a much more difficult problem. With instantaneous communication, it’s trivially simple to determine longitude. The observer merely determines local noon, and then compares that with the local time at a known longitude. The difference in time can quickly be converted to difference in longitude. If it is noon at my location, and I know that it is 6:00 PM at Greenwich, then I instantly know that I am 90 degrees west of Greenwich. The time diference is 6/24 of one day, which is 1/4. Therefore, the difference in longitude is 1/4 of 360 degrees, or 90 degrees.

Of course, instantaneous communication was not availalbe for most of the history of navigation. Therefore, the problem remained formidable. It wasn’t until the late 1700’s that sufficiently accurate chronomoters became available. And even then, a backup method (careful observation of the eclipses of known stars by the moon) involving laborious calculations was required.

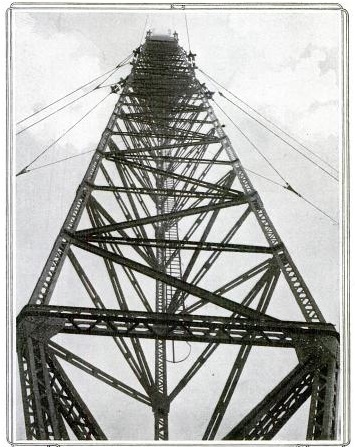

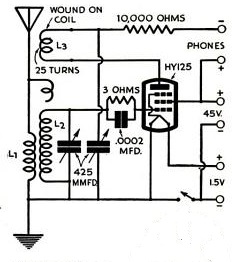

These problems were solved by the use of wireless time signals. A mariner could set his chronometer accurately (generally, to about a tenth of a second) by use of time signals broadcast by stations such as NAA in the United States or the Eiffel Tower in France.

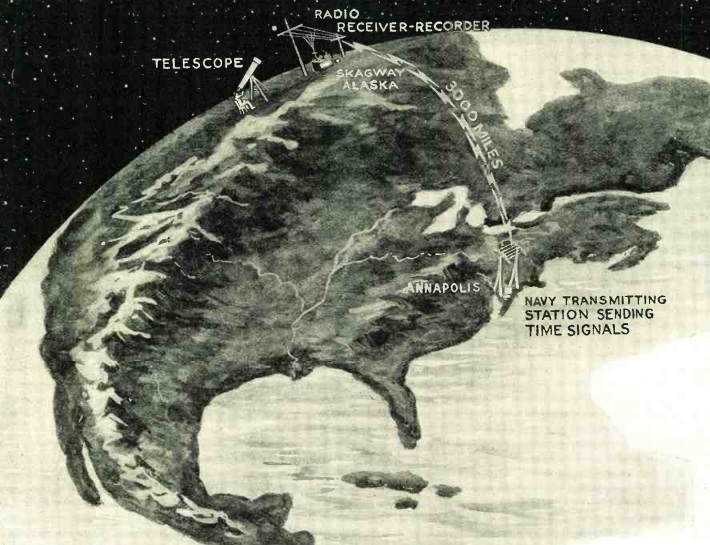

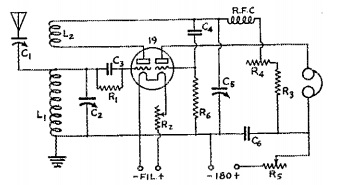

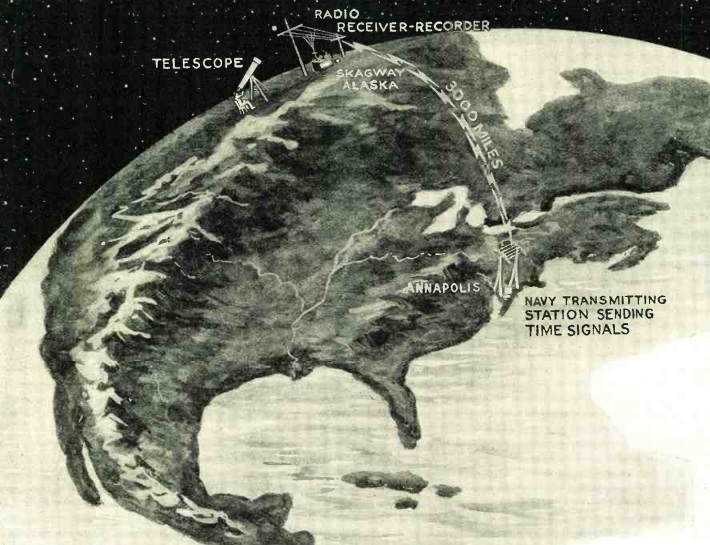

But even as recently as 90 years ago, this problem was still receiving attention, as shown by the article in the November, 1924, issue of Radio News. Listening to the time signal by ear and noting the time on the chronometer was accurate enough for maritime navigation. But for land surveying, a more precise automated method was necessary. Telegraph lines could be used, but the relays used in long lines introduced a delay. Radio was ideal, since the only delay was the speed of light, and even that could be accounted for. The article explains how the time radio time signal from the naval observatory was graphed along with the time from a locally calibrated chronometer. The result was a very accurate indication of the time difference, and thus the longitude difference, between the two locations.

The article shows how the time signal from Annapolis, Maryland, was used to determine exact longitude in Skagway, Alaska, 3000 miles away.

Read More at Amazon