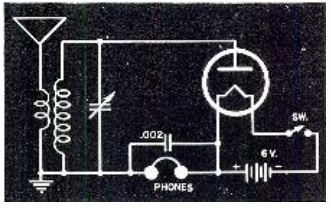

Minneapolis mayor either “flashing a known gang sign” or “pointing.” KSTP photo.

By now, we have all seen KSTP reporter Jay Kolls story about “a photo of Minneapolis Mayor Betsy Hodges posing with a convicted felon while flashing a known gang sign.”

The conventional wisdom is that the mayor was merely pointing at the person, and I tend to agree with that interpretation of the picture. And since the convicted felon in question is African-American, the conventional wisdom, is also that Kolls and KSTP are racist.

Before we decide whether Jay Kolls is racist, we need to first figure out whether you and I are racist. I’m a white Republican, so presumably, I’m the last person who can provide good information about racism. On top of that, I have the distinction of having gone through 13 years of the Minneapolis Public Schools during a time in which I encountered exactly one (1) fellow student who was African-American. And it turns out she was adopted. In short, I’m the kind of person one can probably count upon to be racist.

It turns out I am a racist. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t listen to me, because you’re probably a racist too.

When I say that I’m a racist, I guess it’s important to give a little bit of definition. It can mean two things. It can mean that I am hateful toward certain people because of their race. That definition doesn’t fit me, and it probably doesn’t fit you. There are a handful of people who fit that definition, and anything I say or anything you say won’t make much difference. Fortunately, in my experience, there are very few people who fit into that category. They’re probably a lost cause, and there’s not much you and I can do to change them.

I’m not that kind of racist, and neither are you. But I do make judgments about people based on their race, and so do you. I’ve come to realize this over the last few years in my business as a Continuing Legal Education provider. Lawyers in most states need a certain number of hours of continuing legal education per year, and I provide those classes. In Minnesota, attorneys need two credits of “elimination of bias,” a subject I assumed that I was completely unqualified to teach. But I kept getting requests, since those were the credits that Minnesota attorneys needed. Finally, I put together a course, and I was hard pressed to fill up one hour with meaningful content. I found some reports prepared by the Minnesota Supreme Court, and we talked about them. Over the years of presenting this course, it has grown, and I can now easily discuss the subject for well over two hours. Everyone gets their full credit and they go away happy. And it turns out that they actually learn something in the process. But I probably learned more than they did. learned that I’m a racist, and so are you.

This is a natural effect of my background, and it’s also a natural effect of your background. As noted above, I went through 13 years of school without encountering very many black students. I don’t remember the incident, but the first black person I met was apparently an emergency room physician when I was about four years old. I got my head cracked open (which some say explains many things), and I was rushed to the emergency room to have it stitched back together. The doctor faced with the task of sewing me back together was black. My parents were horrified. They weren’t horrified because the doctor was black; they were horrified that I would blurt out something embarrassing, because I had never seen a black person before. We didn’t have black people where we lived.

It turns out that I didn’t blurt out anything embarassing, and I apparently didn’t even notice. I was apparently too concerned with my injuries to notice the skin color of they guy sewing me back together. (I have reflected over the years that it was somewhat remarkable that a black man was a doctor in 1965. This took place in Indiana, and it was later explained to me that the doctor was probably from the South and went to school in the South, but had to move to Indiana in order to work as a doctor.)

My first real interaction with a black person was with my seventh grade math teacher. He was a pretty good teacher, and as I recall, he was one of my favorite teachers. And he was black. This was not a big deal to me at all, since I had been instructed, quite correctly, over the previous six years that I should not judge people by the color of their skin. But up until that point, a “black person” was a theoretical concept. I had seen black people on TV, but they were usually on TV only because they were black. They typically weren’t on TV for other reasons. I remember a school assembly, which was probably in 1968, where our white teachers talked about a black man named Martin Luther King. They explained that he was a great man who got shot because he was black. I understood this at a theoretical level, and I knew that there was nothing wrong with black people, even though some people apparently thought that there was.

But until seventh grade, I never had any interaction with a black adult, and I had met only one other black student. I did learn that there were a handful of people who were hateful toward people of other races. One day, when another student was annoyed with something the teacher had done, I heard her mutter under her breath, “dumb n—-.” I was shocked, because I had been told for six years that this was wrong. I knew that there was one nutcase in Memphis who hated people because of the color of their skin, but it was rather shocking to know that one existed in person. But that was the exception. I’ve never met too many people like that. Unfortunately, they’re probably a lost cause.

Even though I went to an all-white school in an all-white neighborhood, other than this single example, I never encountered a single person who was hateful toward other people because of the color of their skin. I’m sure there were other examples. And I’ve later heard of other examples right in my old neighborhood. But these were the exception. Most people didn’t hate other people. I certainly didn’t. And I doubt if you do.

But I just told you that I was a racist and that you’re a racist. How to I reconcile this contradiction?

One of the lawyers who took my CLE program related a story about what happened to him in court, and I think it illustrates perfectly why I am a racist. He was in court before a judge, and I think he would attest to the fact that the judge in the case was not racist, in the sense of having any hateful attitudes toward anyone. But she did something that I’m quite certain was motivated by the same racism that I have and that you probably have.

Not surprisingly, in court proceedings, tempers can occasionally flare. When they do, the judge typically gets things back on track by sternly admonishing the people involved. If things get really out of hand, then the judge might impose some sanctions. But generally, a scolding does the trick. This lawyer described an incident that’s not particularly extraordinary. The opposing lawyer was questioning a witness, didn’t like the answers he was getting, and was getting angry. At one point, he reached across the table and grabbed the papers that the witness was consulting. Needless to say, this isn’t the correct procedure. The attorney I know reacted by standing up and shouting something, and probably grabbing for the papers to give back to his client.

The judge’s life experience probably included many situations where two angry lawyers were arguing with each other. Normally, she probably would have done something like say, “gentlemen, stop that!” If it was particularly bad, perhaps she would have held one of them in contempt and leveled a fine. She would have known what to do, because she’s seen angry lawyers before, and knows what to do in order to cool them off. That’s just part of her life experience.

But this wasn’t an ordinary case of two men being angry. It was a case of two angry black men. And to make matters worse, it was two big angry black men. And everyone else in the room was black.

She had probably never encountered this situation before: Two angry black men shouting at each other in a room where she was the only white person. Or even worse, she did have experience (perhaps just from watching TV) with angry black people shouting at each other. From her experience, she knew that this sort of thing usually turned violent. That’s a perfectly logical conclusion: Every time she has seen angry black people before, it turned violent. She had previously seen angry white people calm down. She had never seen an angry black person calm down.

So she did exactly what I probably would have done. She did the racist thing. She pushed the “panic button” and quickly exited the room. Armed bailiffs quickly took her place and restored order. She wouldn’t have pushed the panic button on two white lawyers. So she must be racist, just like me.

She made a judgment based on her experience, and her judgment was probably the same one I would have made. After all, she is racist, and so am I. I don’t have much experience with angry black people, other than what I see on TV. After all, I spent the first 18 years of my life not having any black peers. I had two black teachers, but teachers don’t shout at one another. So I have absolutely no experience with how black people calm down after being angry. I simply don’t have a large enough data set to make any meaningful conclusions. I have to resort to the very limited experience I have. So if I were the judge and two angry big black lawyers were shouting at one another, I would press the panic button. But since I have a lot of experience with angry white people, I wouldn’t push the button. In my experience, angry white people rarely resort to violence.

So we can safely conclude that the judge in that case was racist, and we can safely conclude that I am a racist. I’m not a hateful person, and I doubt if the judge was either. We simply make judgments based on what we observe, and based upon our personal experiences.

We now turn to the photo of the mayor of Minneapolis and an African-American man. After giving the matter a little thought, I have come to the conclusion that the two are engaged in a behavior known as “pointing at one another.” I have noticed that politicians like to point at people. For example, when I saw Sen. Dave Thompson at the State Fair, I waved at him. Since he’s a politician, he did what politicians often do: He pointed at me. Other politicians have pointed at me, and I’ve seen politicians point at other people. If a photographer had captured a picture of Sen. Thompson and me, there would be little doubt about what was going on. Everyone would agree that he was pointing at me. It wouldn’t be particularly newsworthy, because we’re all used to seeing white people point at other white people.

But when I first saw the picture of the mayor pointing at an anonymous black person, that wasn’t my first reaction. My first reaction was, indeed, that she was foolishly “flashing a gang sign.” I had this reaction because I was a racist, in the sense that I have no experience (certainly no experience in the first 18 years of my life) of black people pointing at one another. My only experience with black people using hand gestures is what I’ve seen on TV. So I used my experience to judge the situation, and I quickly came to the conclusion that she was “flashing a gang sign,” probably after having been goaded into doing so.

It turns out I was wrong, but that was my initial reaction. I thought it was a gang sign, because I’m racist. I would have pushed the panic button in the courtroom, because I’m racist. So it is indeed a correct conclusion if you say that the judge was racist, or that KSTP was racist, or that Jay Kolls was racist, or that I am racist.

But it’s a big mistake to stop there. Because it’s safe to say that you are also racist. You have your own life experiences, and you also use those life experiences to make judgments. Usually, those judgments are correct, but sometimes they are wrong. And because your experiences are skewed toward those of your one race, this means that some of your judgments are racist. You’re not evil and you’re not hateful. But you are racist. Therefore, very little is accomplished by simply branding me, or KSTP, or Jay Kolls as being racist. Very little is accomplished by lumping us in with the guy who shot Martin Luther King or even the kid who muttered “dumb n—–” about the teacher.

If you want to hear more, feel free to download the podcasts of my “elimination of bias” CLE program. If you’re a lawyer, you can get 2 CLE credits for $20. But there’s no cost to listen to the podcast.