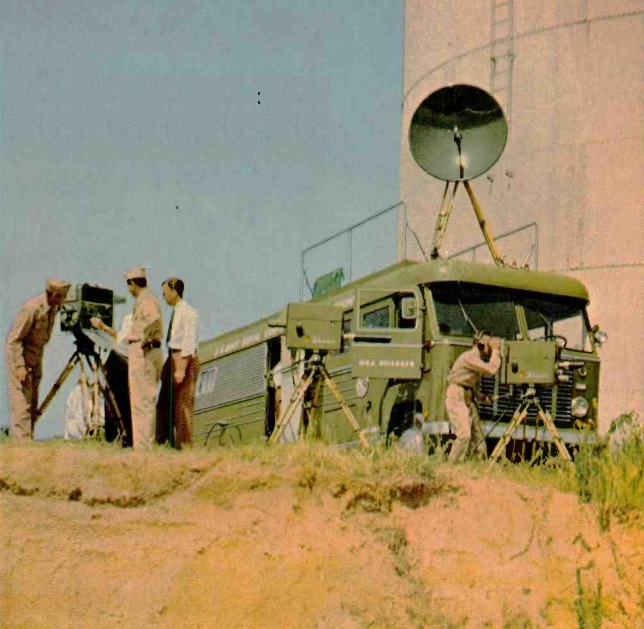

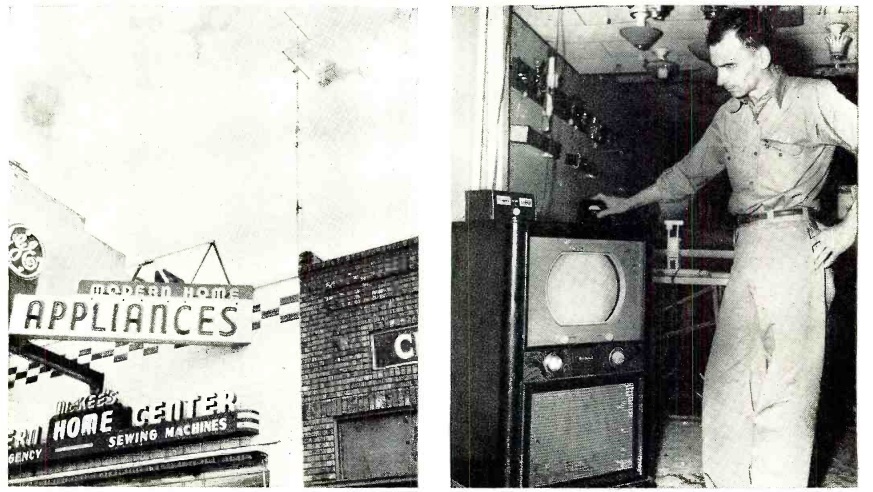

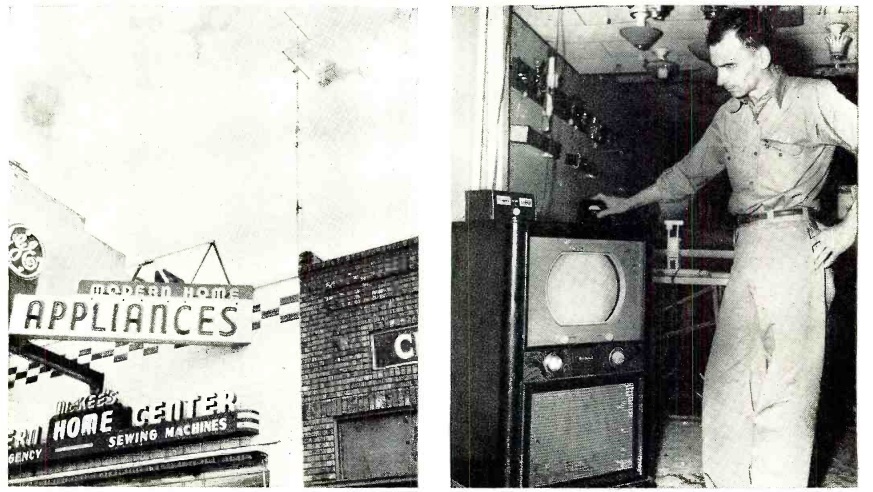

Shown here seventy years ago is Lawrence Pickerell, technician for McKee’s Modern Home Center of Longmont, Colorado. The store had entered the television business, notwithstanding the fact that the closest station was 500 miles away in Omaha, Nebraska.

Shown here seventy years ago is Lawrence Pickerell, technician for McKee’s Modern Home Center of Longmont, Colorado. The store had entered the television business, notwithstanding the fact that the closest station was 500 miles away in Omaha, Nebraska.

Pickerell, along with owner Howard McKee, had been associated with another store in Iowa. While at that store, a closer-in station was scheduled to be built, but originally, the closest station was a hundred miles away. But their store went right wo work doing everything to pull in the fringe station.

At times, reception was poor, but at other times, it was acceptable. While they didn’t make many sales at that time, they gathered a tremendous amount of local publicity, and their service department gained a lot of practical experience with television. When a local station came on the air, they already had the reputation as “the television store,” and they wound up with most of the business.

When McKee bought the store in Colorado, the situation was even worse, and they weren’t even in the fringe area of any station. Undaunted, they decided to put up a tower and hope for the best. Since the closest station in Omaha was channel 6, WOW-TV, so they put up a stacked array tuned to channel 6, and had the foresight to include a rotor. During the sprint of 1950, they pulled in other stations quite frequently due to Sporadic E, with similar results in 1951. They noted that reception was best over the noon hour, from 5:00 – 6:00 PM, and after 8:30. During 1951, 8:00 AM and early afternoon were the best. They noted that conditions were consistent with short skip on the 10 meter band.

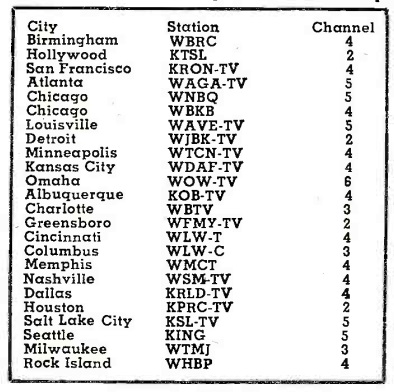

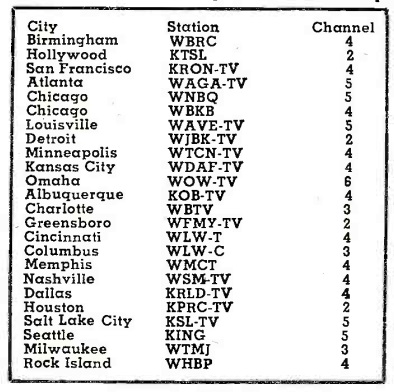

About 25% of the stations received were “program quality,” with another half being passable quality. The other 25% were intermittent. The complete log is shown here, ranging from Seattle to Atlanta. Even though the antenna was tuned to channel 6, most stations were channels 2-5. As would be expected, they didn’t pull in any high-band stations. The most consistent logging was KPRC, channel 2, Houston, Texas. In many cases, the best signal was obtained by pointing the antenna at nearby Longs Peak, elevation 14,000 feet.

About 25% of the stations received were “program quality,” with another half being passable quality. The other 25% were intermittent. The complete log is shown here, ranging from Seattle to Atlanta. Even though the antenna was tuned to channel 6, most stations were channels 2-5. As would be expected, they didn’t pull in any high-band stations. The most consistent logging was KPRC, channel 2, Houston, Texas. In many cases, the best signal was obtained by pointing the antenna at nearby Longs Peak, elevation 14,000 feet.

According to this undated matchbook, the store was playing up television, and was located at 350 Main Street. According to Google Street View, the building is still standing, and until a recent move, housed Jensen Guitars and the Willow River Music Emporium. The TV antenna appears to be gone.

The photos appeared in the December 1951 issue of Radio & Television News.

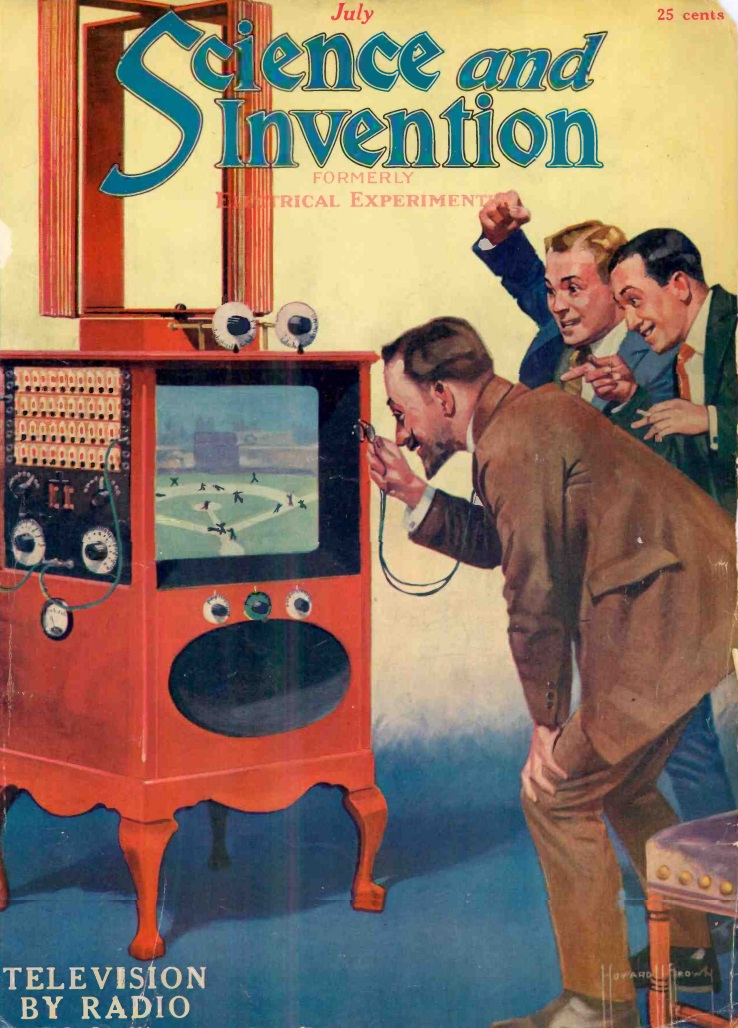

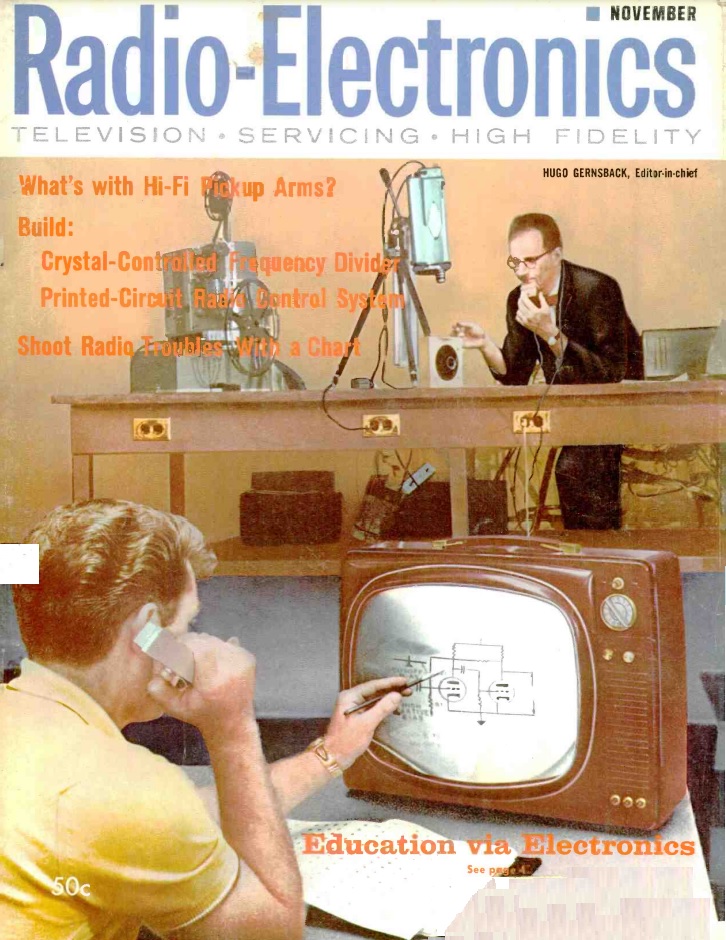

Shown here is 1962’s answer to the Google Glass. The cover of the September 1962 issue of Radio Electronics shows this wearable CRT display, dubbed a “television monocle.”

Shown here is 1962’s answer to the Google Glass. The cover of the September 1962 issue of Radio Electronics shows this wearable CRT display, dubbed a “television monocle.”Google isn’t currently selling their version retail, but wearable displays such as the one shown here are currently available.