Fifty years ago, this young woman was doing something one wouldn’t have dared doing in the first decades of television–she was watching it in the pool. In the 1950s or 60s, this would have been a highly reckless thing to do, since the high voltages involved could have lethal consequences if they came into contact with water. But by the 1970s, the art had progressed to the point where battery operated televisions were available. And the July 1971 issue of Popular Mechanics contained a review of the available offerings, penned by prolific electronics writer Len Buckwalter (who has appeared here many times previously).

Fifty years ago, this young woman was doing something one wouldn’t have dared doing in the first decades of television–she was watching it in the pool. In the 1950s or 60s, this would have been a highly reckless thing to do, since the high voltages involved could have lethal consequences if they came into contact with water. But by the 1970s, the art had progressed to the point where battery operated televisions were available. And the July 1971 issue of Popular Mechanics contained a review of the available offerings, penned by prolific electronics writer Len Buckwalter (who has appeared here many times previously).

Buckwalter starts by noting that the “portable” TV had been around for a long time, but it had an AC power cord and weighed up to 90 pounds. The only concession to portability was the handle slapped on top as an afterthought. But now, there were true portables hitting the market: Sets that ran off batteries and/or 12 volts, and weighing as little as 2 pounds, although the average was 15-20. There were even two color sets hitting the market, and prices started at under $100.

There were still power requirements, and most of the battery sets used rechargeable batteries. Those were good for only a couple of hundred recharge cycles, so he cautioned that for viewing outside, it would be wise to install a power outlet. Some of the very small sets used standard flashlight batteries, but most had a special rechargeable power pack. In some cases, it was built in, but in others, it was a separate unit, which made the set more compact when the battery was not necessary, such as in a car or boat.

A few of the samplings are shown at the left. At the top was Heathkit’s offering, which sold for $124.95, and could be put together in 15-20 hours. The detachable base of this set, the GR104A, contained the batteries.

Below that was the Symphonic 3-incher, with a built-in cassette recorder and AM-FM radio. Below that, for the well heeled, was Hitachi’s 12 inch color set, which sold for $369.95. Below that was a Panasonic 5-inch model whose screen folded away when not in use. It also contained an AM-FM radio.

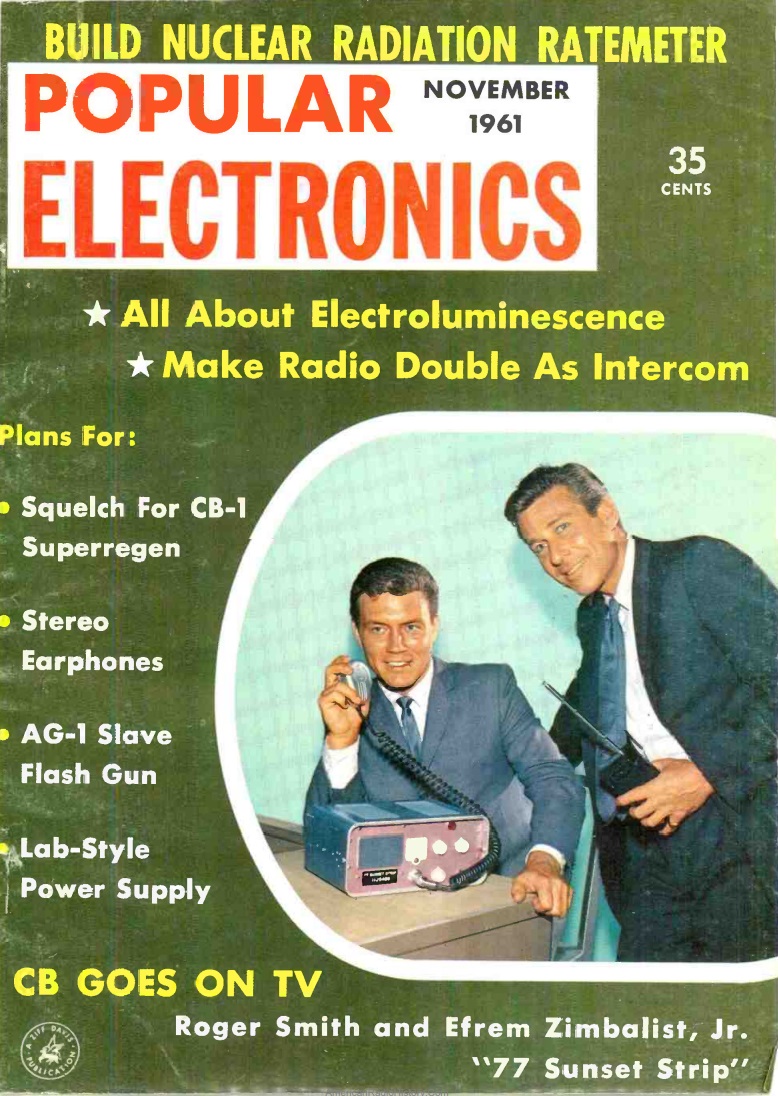

Sixty years ago this month, the cover of the November 1961 issue of Popular Electronics featured the stars of the hit TV private detective drama 77 Sunset Strip. Roger Smith and Efrem Zimbalist, Jr., are shown with a new co-star, namely CB radio. Smith is shown at the mike of a base transceiver, and Zimbalist is shown with a handheld unit. The base unit looks like it might be a Polytronics Poly-Comm Model N.

Sixty years ago this month, the cover of the November 1961 issue of Popular Electronics featured the stars of the hit TV private detective drama 77 Sunset Strip. Roger Smith and Efrem Zimbalist, Jr., are shown with a new co-star, namely CB radio. Smith is shown at the mike of a base transceiver, and Zimbalist is shown with a handheld unit. The base unit looks like it might be a Polytronics Poly-Comm Model N.