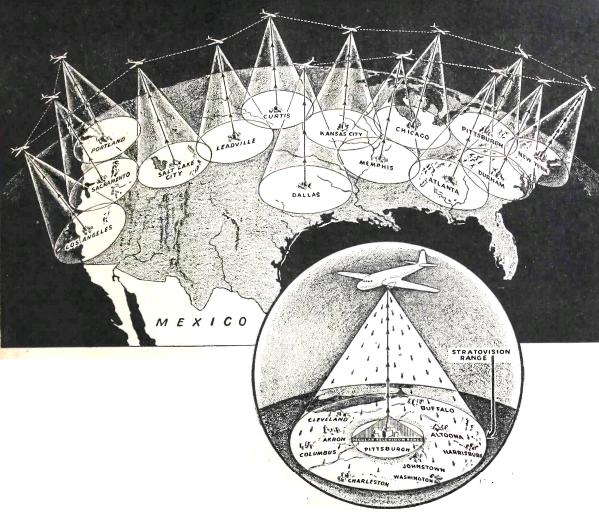

Seventy years ago this month, Radio Craft magazine, October 1945, introduced the concept of Stratovision, and the illustration above showed how it could work.

The war was over, and the American public was hungry for television. A handful of markets already had stations using the same format that would remain in use for seventy years. For example, the predecessor of WNBT-TV came on the air in New York in 1939. And the predecessor of WABD signed on in 1944. And starting in 1942, Los Angeles had the station that would become KTLA. But most of the nation was dark as far as television signals. To get signals to a significant proportion of the populations would require hundreds of stations. And getting network programs to those stations would require either hundreds of microwave relay stations, are a coaxial network estimated to cost a hundred million dollars.

Stratovision provided an alternative. The plan was proposed in 1945 by Westinghouse, and was the brainchild of engineer C.E. Nobles. Under the plan, fourteen aircraft would fly at the predetermined locations shown on the diagram at an altitude of 30,000 feet where they would continually orbit their designated location. They would transmit VHF and UHF television signals, as well as FM broadcasts. Because of the antenna height, each plane would provide a good broadcast signal to an area 422 miles in diameter. And because there would be no terrain that would need to be overcome, the transmitters could operate with much less power than ground-based stations.

The system also solved the problem of delivering network programming. Only eight planes would be required to link New York with Los Angeles. The planes would establish a reliable network whenever they were in flight, and the fourteen planes would provide broadcast television to 78% of the country’s population. The plan called for each plane to broadcast four television and five FM signals.

The plan may appear far fetched to some, but it is sound, and would result in a workable national network. The system was tested by Westinghouse in 1948 and 1949, as seen in this photo. In one 1949 test, the aircraft shown here, a B-29, relayed the signal of WMAR-TV in Baltimore on channel 6, using a 5 kW video and 1 kw aural transmitter. In June 1948, the same aircraft was used to rebroadcast the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia for one hour. As part of the test, a receiver was set up in Zanesville, Ohio, where it was used to demonstrate to the gathered newspaper reporters that the system was capable of reaching small town and farm homes.

The plan may appear far fetched to some, but it is sound, and would result in a workable national network. The system was tested by Westinghouse in 1948 and 1949, as seen in this photo. In one 1949 test, the aircraft shown here, a B-29, relayed the signal of WMAR-TV in Baltimore on channel 6, using a 5 kW video and 1 kw aural transmitter. In June 1948, the same aircraft was used to rebroadcast the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia for one hour. As part of the test, a receiver was set up in Zanesville, Ohio, where it was used to demonstrate to the gathered newspaper reporters that the system was capable of reaching small town and farm homes.

Reception reports were solicited, and many were received. From the reports, Westinghouse confirmed that eight planes would provide the transcontinental relay.

There’s nothing technically unfeasible about Stratovision. The reason why it never took off (pardon the pun) was probably the mere fact that broadcast stations did spring up nationwide. They were initially provided with programs by kinescope recordings, but microwave and coaxial transmission quickly came into place. For example, by 1950, the Minneapolis/St. Paul market was getting the national networks live, by means of a coaxial cable from Des Moines, which was in turn linked to Chicago by microwave relay. Once the network signal was in place, there was no need for Stratovision’s relay services. And by this time, most major cities had multiple stations, and smaller markets had at least one. And for those far in the hinterlands, there were herculean efforts to get the distant terrestrial signals, such as those use in the tiny communities of Ellensburg, Washington and Marathon, Ontario.

But despite the fact that Stratovision was never adopted for its intended purpose, it did live on, and continues to do so, in some specialized niches. For example, between 1961 and 1968, educational programs were broadcast from two DC-6AB aircraft based at Purdue University by the Midwest Program on Airborne Television Instruction (MPATI). The MPATI aircraft would fly in a figure-8 pattern for six to eight hours at a time at 23,000 feet above a point just north of Muncie, Indiana. Prerecorded educational programs were broadcast on UHF channels 72 and 76, with call letters KS2XGA and KS2XGD. The transmission diameter was 200 miles, and covered both the Chicago and Detroit metropolitan areas.

Between 1966 and 1972, the U.S. Navy used Stratovision to broadcast two channels in the area surrounding Saigon, South Vietnam. One channel was intended for the Vietnamese audience, with the other providing information and entertainment programs to U.S. servicemen. Armed forces programs were carried on channel 11, with call letters NWB-TV, with the Vietnamese program on channel 9 with call letters THVN-TV. The aircraft also broadcast on 1000 kHz AM and 99.9 MHz FM. The Vietnamese program typically ran 1-1/2 hours per day, with the armed forces channel running three hours per day. American programs included Bonanza, Perry Mason, Ed Sullivan, and the Tonight Show.

Pennsylvania Air National Guard Commando Solo aircraft preparing to depart for emergency broadcasts to Haiti in 2010. Department of Defense photo.

The U.S. military continues to use EC-130 Commando Solo aircraft to provide PSYOPS broadcasts during war. Most recently, only radio programming has been used. But the aircraft is capable of television transmissions. For example, in 1999 in the former Yugoslavia, some television programming, using Yugoslavian broadcast format, was transmitted from aircraft. Typically, Commando Solo transmits an FM program, along with broadcasts on the standard AM band and short wave. For AM and short wave, the airborne transmitter has no particular advantage, other than providing a secure location to house the station. But on FM, the signal, like the original Stratovision concept, takes advantage of the aircraft’s altitude, and can provide a strong broadcast signal over a large area with a relatively low powered transmitter. The photo here shows a Pennsylvania Air National Guard Commando Solo aircraft preparing to depart for Haiti to make emergency broadcasts in the wake of the 2010 earthquake.

During the 2011 attack on Libya, Commando Solo aircraft broadcast information. Transcripts of the broadcasts are available at PsyWar.org. Since the Libyan broadcasts were carried on short wave as well as FM, they were heard by short wave listeners worldwide, including myself. A recording of the transmissions can be found at this video:

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

![]()

Pingback: Cuba-U.S. TV Broadcast Aircraft Relay | OneTubeRadio.com

Pingback: Whatever Happened to Stratovision? | The Flight Blog

Pingback: 1944: Sky Radio Blankets Enemy | OneTubeRadio.com