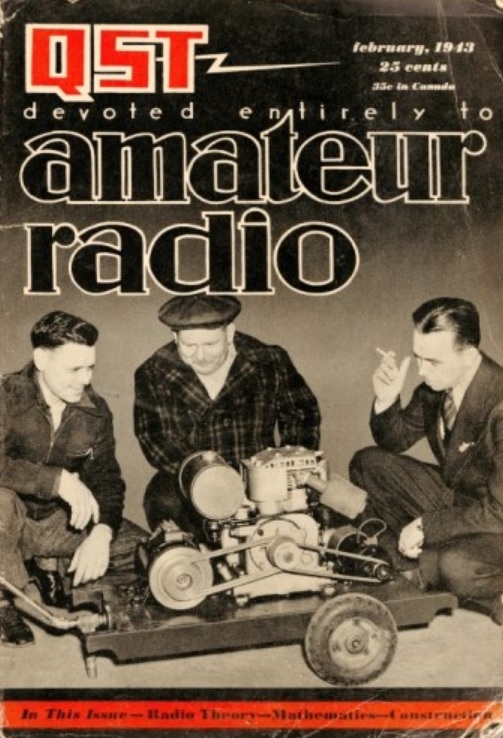

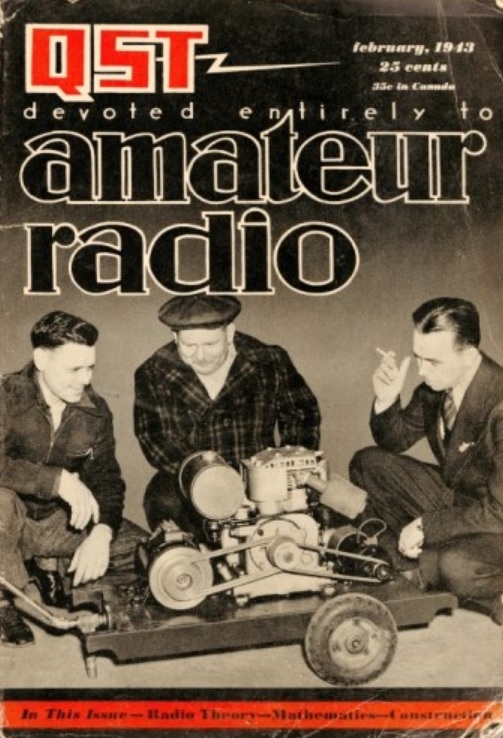

Eighty years ago this month, the February 1943 issue of QST showed this emergency generator. Hams might have been off the air for the duration, but they still had an interest in emergency needs, including WERS operations.

Eighty years ago this month, the February 1943 issue of QST showed this emergency generator. Hams might have been off the air for the duration, but they still had an interest in emergency needs, including WERS operations.

It was powered by a Briggs & Stratton gasoline engine normally rated at 1-3/4 HP, but the accompanying article noted that it was capable of up to 2-1/2 HP maximum as shown here. It was capable of putting out 120 volts thanks to a salvaged Dodge 12-volt generator, rewound, and was capable of putting out over 1400 watts. The field coils needed power, and that was provided by a second six-volt generator also driven by the engine.

The estimated cost of the whole unit was said to be $7.50, although the author admitted that this figure might have been somewhat “under-exaggerated.” The set shown here was the second one constructed, and a third was underway.

One of the gentlemen shown on the cover, although they’re not identified, was apparently Warren Copp, W8ZQ. The article mentioned that he was the father of then-eight-year-old actress Carolyn Lee. We’re not sure exactly why that’s relevant, but like the author of the QST article, we believe that’s the kind of thing our readers would want to know.

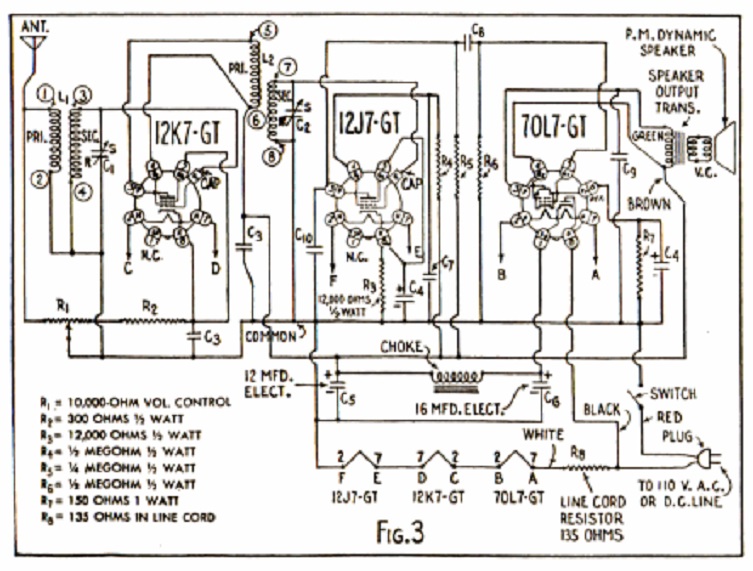

Eighty years ago, domestic radio production had been shut down for over a year, and there would be no new radios for the duration of the war. Therefore, it was every American’s patriotic duty to keep their current radio in working order.

Eighty years ago, domestic radio production had been shut down for over a year, and there would be no new radios for the duration of the war. Therefore, it was every American’s patriotic duty to keep their current radio in working order.