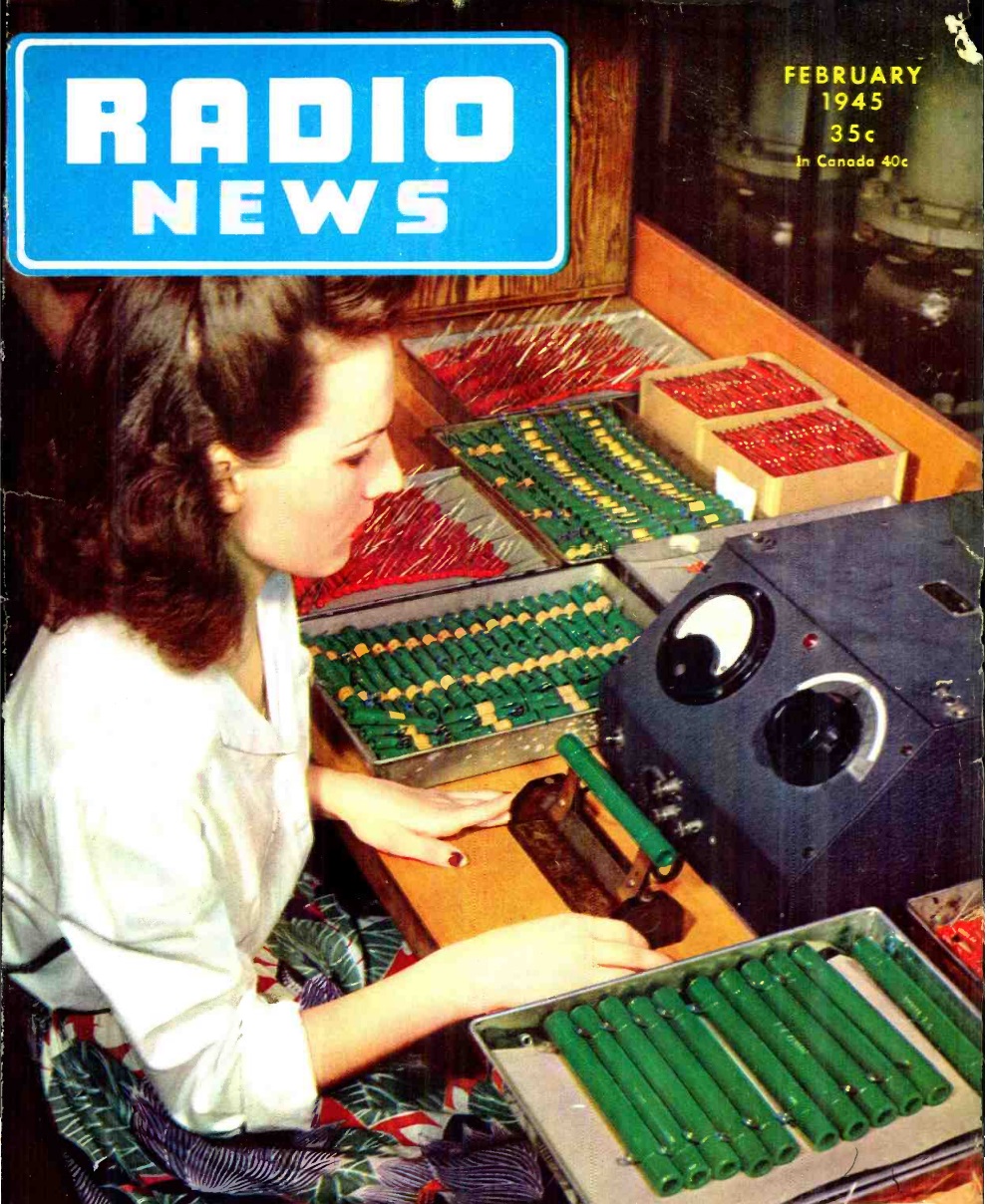

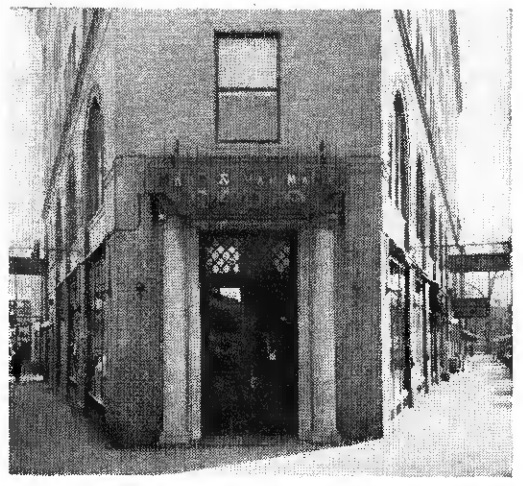

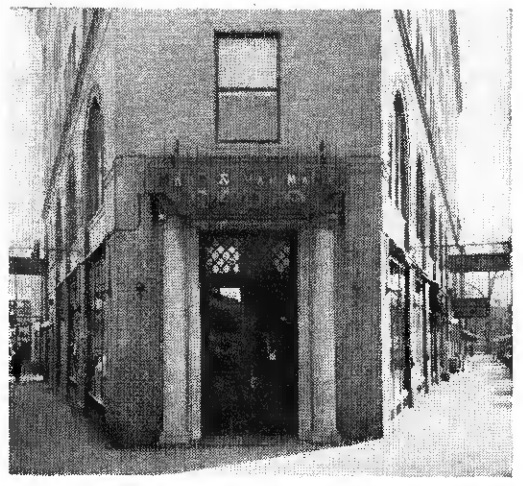

Seventy-five years ago, this trapezoidal building was the home of Mahr & Van Name, a radio dealer at 29 Beach Street, Stapleton, Staten Island, New York. The shop was featured in the February 1945 issue of Radio Retailing.

Seventy-five years ago, this trapezoidal building was the home of Mahr & Van Name, a radio dealer at 29 Beach Street, Stapleton, Staten Island, New York. The shop was featured in the February 1945 issue of Radio Retailing.

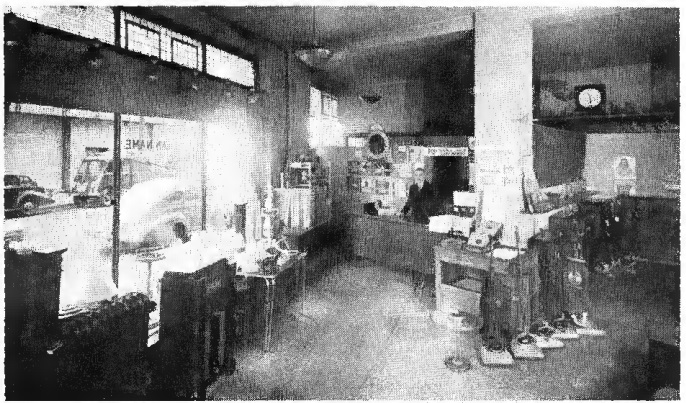

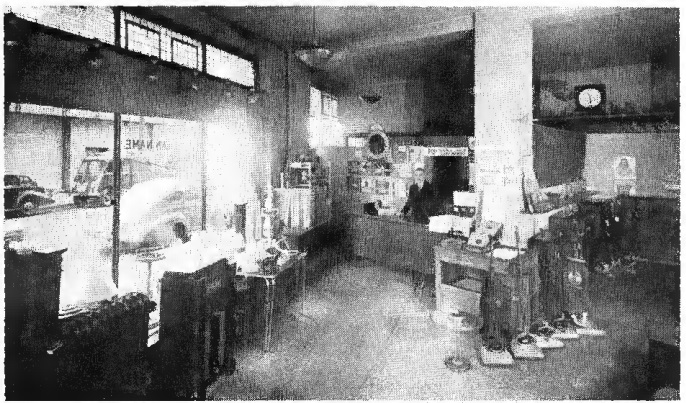

According to the magazine, both before and during the war, the shop stressed quality and material, rather than selling on a grand scale. With wartime shortages, that philosophy proved to be especially important.

Even before the war, the shop also sold table lamps, and those sales, along with service, kept the store open during the war. The owner predicted big things for both FM and TV, both of which the store had sold before the war.

As shown from the current Google Street View shot, the building still stands, although its unclear who occupies the radio shop’s former space.

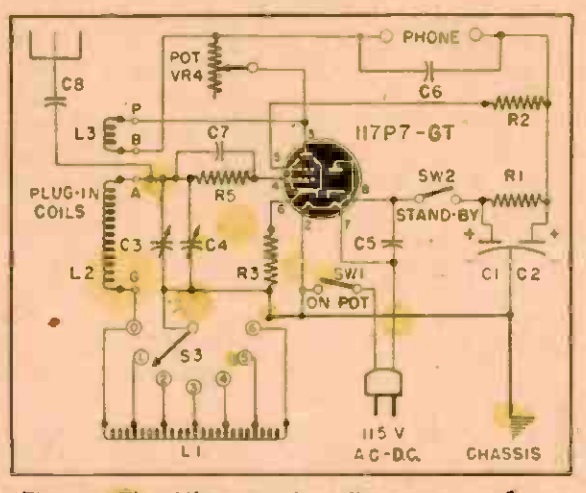

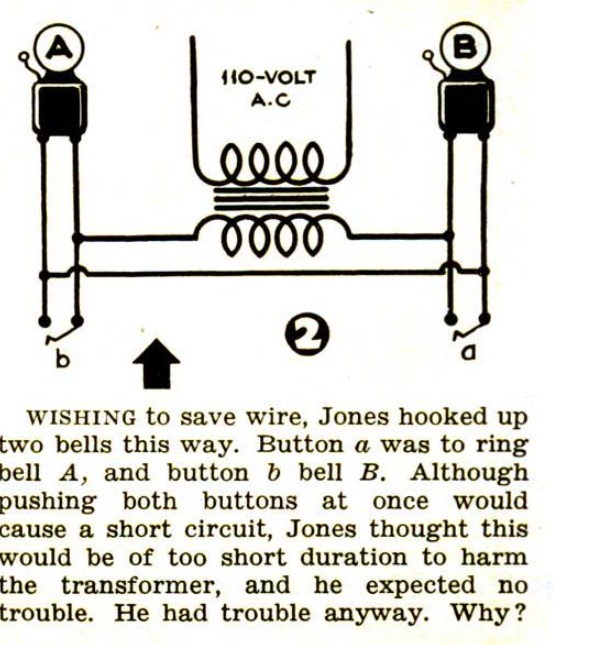

Wartime shortages were undoubtedly the reason that Jones tried to save wire when hooking up his two doorbells. But can you figure out what went wrong? We’ll have the answer tomorrow.

Wartime shortages were undoubtedly the reason that Jones tried to save wire when hooking up his two doorbells. But can you figure out what went wrong? We’ll have the answer tomorrow.