With the Great War, the wireless telegraph was clearly coming of age and was relied upon by the warring powers. The need for wartime communications was best illustrated by the Battle of New Orleans. The War of 1812 should have ended with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent on December 24, 1814, but word didn’t reach Louisiana in time to prevent the Battle of New Orleans from taking place on January 8, 1815.

By the time of the American Civil War, the telegraph had become an important tool of war, and both building and destroying telegraph lines became important military tasks.

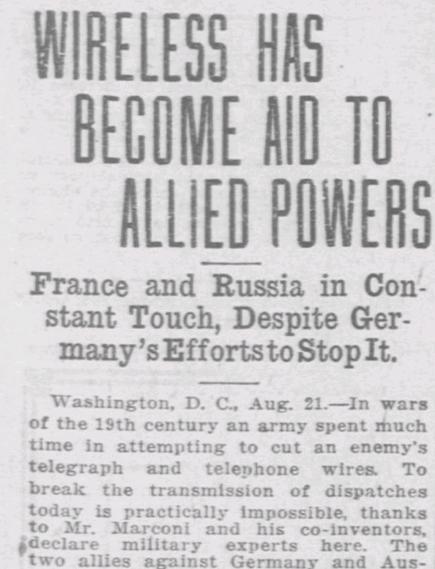

The Great War was the first in which cutting telegraph lines was no longer a strategic priority. This was recognized early in the war, as shown by this report in the El Paso Herald, Aug. 21, 1914:

WIRELESS HAS BECOME AID TO ALLIED POWERS

France and Russia in Constant Touch, Despite Germany’s Efforts to Stop It.

Washington, D. C, Aug. 21. In wars of the 19th century an army spent much time in attempting to cut an enemy’s telegraph and telephone wires. To break the transmission of dispatches today is practically impossible, thanks to Mr. Marconi and his co-inventors, declare military experts here. The two allies against Germany and Austro-Hungary, France and Russia, are probably in constant touch every hour indeed every minute, of the day and night.

The can talk right over Germany, Moscow and Paris can cooperate perfectly. Probably Gen. Joffre and grand duke Nicholaievitch know each of them what the other’s forces are doing from hour to hour.

An incident of the Balkan war shows the remarkable possibilities of wireless. The allies bottled up Adrianople. holding all roads to Constantinople. But in the city was a 1-1/2 k.w. Marconi wireless telegraph station of the portable type. At no time did the station fail, and in the course of the siege, more than 450,000 words were transmitted to headauarters without hitch.

lhe allies attempted to stifle the station by placing wireless outfits to the east and west of Adrianople, but their attempt to “jam” the Turkish signals was in vain.

Usefulness Is Demonstrated.

The usefulness of wireless was also shown in the recall of certain ships at the outbreak of the present war. One ship was brought back after she had proceeded within two days’ journey of Europe, and thus was saved from the enemy.

Many small craft have been seized, because they were at sea. at the outbreak of hostilities and had no wireless. The effect of this experience will undoubtedly be the cause of a wide use of air communications, as a kind of assurance against capture by a hostile warship.

Austria-Hungary has four important government wireless stations; Germany, 17. France, 18; Russia, 28; and Great Britain, 68.

Try To Insure Privacy.

Many means are now used for insuring the privacy of a wireless dispatch. The Marconi stations are designed to obtain this result by changing the wave length of the transmitter at frequent intervals.

This change can be made in a fraction of a second. The operator can shift his “tune” after every three or four words if he considers it necessary. Just before the shift he sends a code letter indicating to which wave length he is about to change. The operator at the station receiving makes the necessary readjustments to follow him without difficulty. It is believed that this system, properly carried out, is eavesdropper-proof.

Eiffel tower station, which France depends upon for communication with Russia, has the advantage that interference is practically impossible, owing to the peculiar sound of the signal emitted.

In other war news, the paper reported that Germany has lodged a protest with the U.S. State Department regarding the German wireless station in New Jersey. Cables between the United States and both France and England were still in operation, without American censorship. But since the German cable had been destroyed, the only method of communication between the United States and Germany was by wireless. The German charge d’affaires protested, and the matter was referred to President Wilson, who the paper noted might impose the same censorship on England and France.

Read More at Amazon