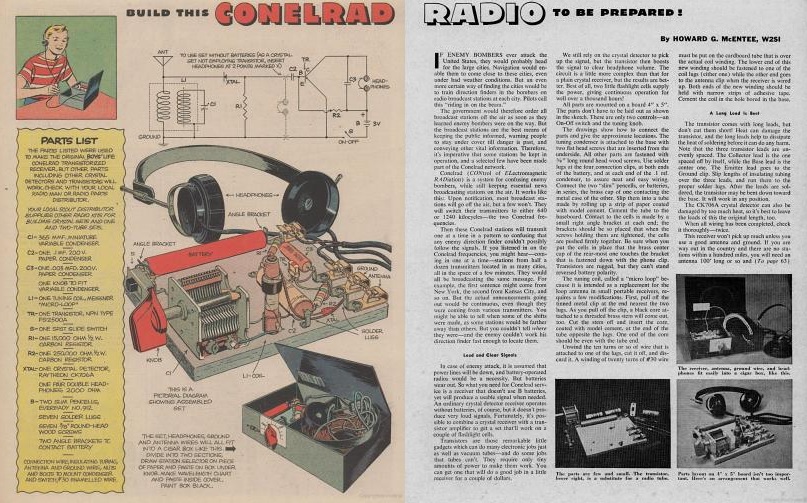

Pedro delivering prizes to lucky winners in BL radio contest. June 1955 Boys’ Life.

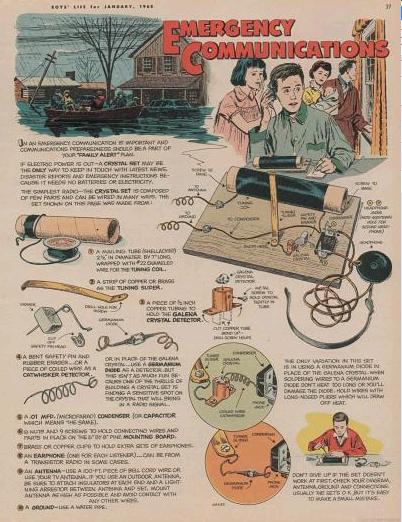

60 years ago this month, Boy Scouts were busy trying to win valuable prizes, including a Hammarlund HQ-140-X receiver, a Hallicrafters S-85 receiver, or a National NC-88 receiver. Unlike prior years, licensed amateurs were not eligible for prizes (probably because they swept them earlier years). But these prizes were available for logging as many stations as possible. Each station counted for one point, each country and U.S. call area 10 points, each state 10 points, and each continent 50 points. There were also bonus points for logging all continents, all states, and all call areas.

There were two classes of entries: one for commercial or surplus receivers, and one for homemade receivers. The contest was in effect during the month of February, 1955. The full rules were contained in that month’s issue of Boys’ Life.

The winners were announced in the June issue. In “Class A” (manufactured receivers), the HQ-140X went to Ralph Overton of Mechanicsville, NY. Norb Harnegie of Berea, Ohio won the S-86.Henry Weir of Charleston, West Virginia, John Bryant of Stillwater, Oklahoma, John Tull of Kansas City, Missouri, and Francis Jacobs of Anson, Maine, won either a Hallicrafters S-38D or a National SW-54.

In “Class B” (homemade receiver), the winner of the Hammarlund was Gary Dobbs of Arlington, California, and Jay Hall of Maplewood, New Jersey took the second place prize of a National NC-88. Winning either an S-38D or SW-54 were Walter Piper of Ravenna, Ohio, Paul Stein of Uvalde, Texas, Don Cannon of Lubbock, Texas, Howard Ferber of Brooklyn, New York, and Bob Samson of Chicago, Illinois.

Over 200 other prizes were awarded to some of the 1049 entrants.

Unlike earlier contests, licensed hams were not eligible for prizes in this run of the contest. However, at least two of the winners went on to become licensed hams. As explained on my website, only a few call books are available for online searching, and the first one after this contest is from 1972, sixteen years later. There might have been more, since some had common names, and some might have moved to different call areas. But Norb Harnegie of Berea, Ohio, who won the S-86. was licensed in 1972 as W8FCV. And Francis Jacobs of Anson, Maine, was licensed in 1972 as W1EST.

It would be interesting to know how these rather generous prizes affected the winners. If you Googled your name and found this page, I would love to hear from you in order to write a follow-up. You can reach me at clem.law@usa.net, or leave a comment below.

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

![]()