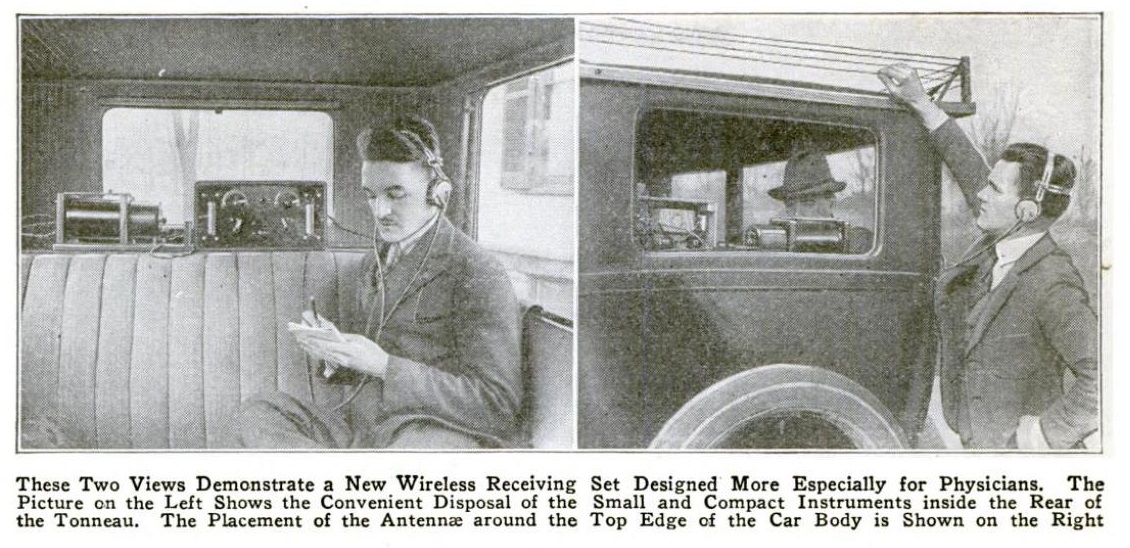

Shown here is one of the first portable radios, from a hundred years ago. The editors of the September 1921 issue of Popular Mechanics were apparently a little bit unclear on what to call it, so they settled on “phonographic suitcase.” But it’s really a six-tube TRF portable radio receiver, conveniently mounted in a suitcase.

Shown here is one of the first portable radios, from a hundred years ago. The editors of the September 1921 issue of Popular Mechanics were apparently a little bit unclear on what to call it, so they settled on “phonographic suitcase.” But it’s really a six-tube TRF portable radio receiver, conveniently mounted in a suitcase.

The magazine noted that music by wireless was nothing new, but up to that point, it had been necessary to go to a receiving station to hear it. But now, the receiving station could be carried about to where it was needed. The set weighed in at barely 30 pounds, which included everything including two 1.5 volt A batteries and two 20 volt batteries to supply the B+.

The inside of the cover was a receiving coil with 21 turns of 28 gauge wire. At the bottom was a horn coupled to a telephone receiver, which presumably supplied room-filling volume from stations within about eight miles. Once tuned, the set performed while closed. A button near the handle was turned, and this was connected to the inside switch. The only opening to the outside world was the opening for the horn, shown at left.

The inside of the cover was a receiving coil with 21 turns of 28 gauge wire. At the bottom was a horn coupled to a telephone receiver, which presumably supplied room-filling volume from stations within about eight miles. Once tuned, the set performed while closed. A button near the handle was turned, and this was connected to the inside switch. The only opening to the outside world was the opening for the horn, shown at left.