Fifty years ago this month, the September 1971 issue of Elementary Electronics carried a feature describing a proposed system known as Electronic Route Guidance System (ERGS). While it was apparently never adopted, the system was tested in the Washington, D.C. area, and amounted to an early prototype of Google Maps.

Fifty years ago this month, the September 1971 issue of Elementary Electronics carried a feature describing a proposed system known as Electronic Route Guidance System (ERGS). While it was apparently never adopted, the system was tested in the Washington, D.C. area, and amounted to an early prototype of Google Maps.

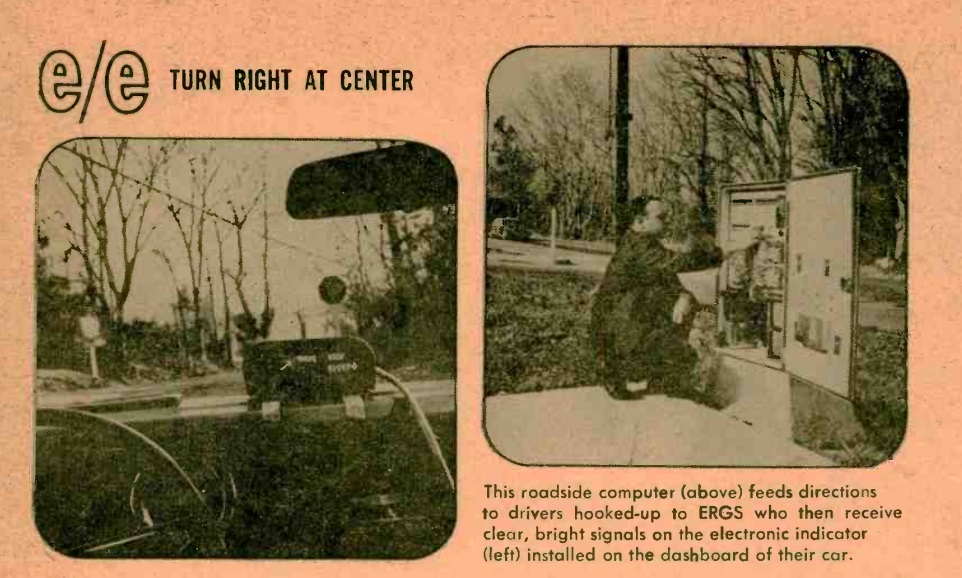

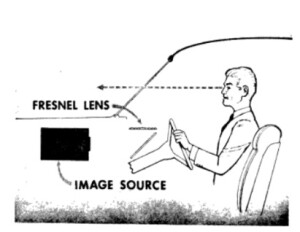

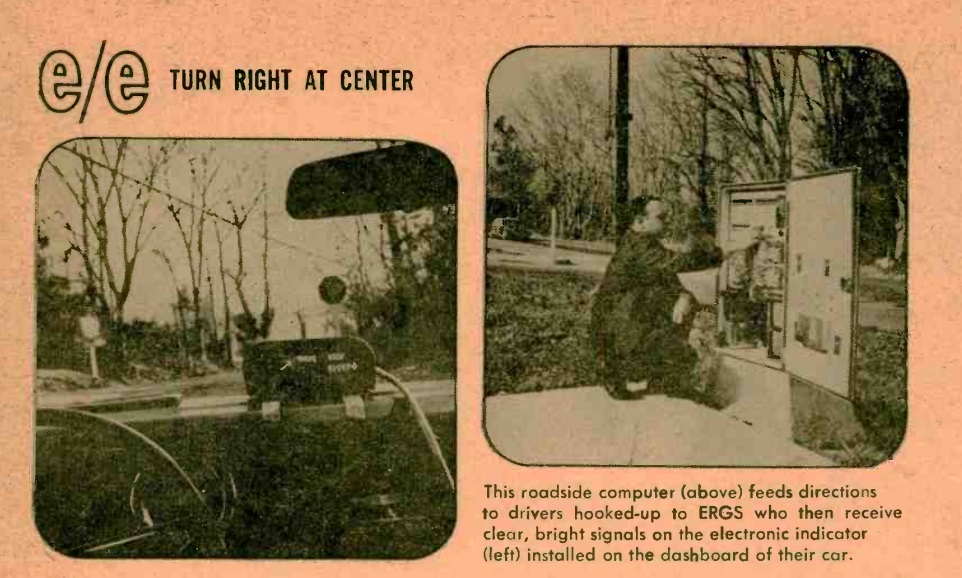

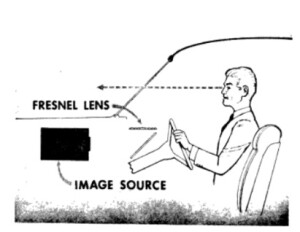

he system would provide directions to your destination as you drove. It was ultimately envisioned as a nationwide system. The user would enter a 6-digit alphabetical code into the car’s unit. This code could be looked up in a directory (or provided by a person at the destination) and would represent one of up to four million destinations. As he or she drove along, the system would continually give directions of whether to go straight, turn right, or turn left. In many cases, the instructions would alert the driver to take the second right or the third left. Directions would be given on a heads-up display, such as shown at left, or on a unit mounted on the dashboard, as shown above.

he system would provide directions to your destination as you drove. It was ultimately envisioned as a nationwide system. The user would enter a 6-digit alphabetical code into the car’s unit. This code could be looked up in a directory (or provided by a person at the destination) and would represent one of up to four million destinations. As he or she drove along, the system would continually give directions of whether to go straight, turn right, or turn left. In many cases, the instructions would alert the driver to take the second right or the third left. Directions would be given on a heads-up display, such as shown at left, or on a unit mounted on the dashboard, as shown above.

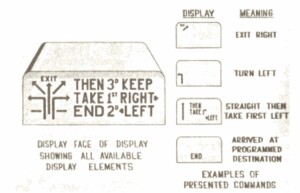

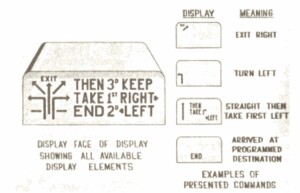

This was all done long before the advent of GPS, and the position locating and storage of directions were elegantly simple. To service four million destinations, up to 200,000 intersections would have installed loop antennas under the pavement. Each loop antenna would be connected to a receiver and 2-watt transmitters operating on 170 and 230 kHz. Cars would be equipped with a similar system. As a car drove over a loop, a 230 kHz signal from the pavement would be detected by the car, and this would trigger the car to transmit its destination, in the form of a 25-bit binary code, on 170 kHz. This would be received by the pavement antenna. For each of the 4,000,000 possible destinations, the system would then have locally stored the proper direction to go to get to that destination. The pavement antenna would then transmit that information as a 16-bit signal, which would be displayed on the 16-element display shown at right. Only the needed segments would be lighted, allowing a wide variety of messages.  The entire process would take 21.0-24.3 milliseconds. The system used on-off keying with a data transmission rate of 2000 bits per second. When the driver passed over the station closest to the final destination, the display would indicate “END.”

The entire process would take 21.0-24.3 milliseconds. The system used on-off keying with a data transmission rate of 2000 bits per second. When the driver passed over the station closest to the final destination, the display would indicate “END.”

More technical details of the system can be found in this 1969 report of the Federal Highway Administration.

If a driver missed a turn, the system would be automatically self-correcting. At the next intersection equipped with a loop antenna, the system would show directions to the programmed destination, from that location.

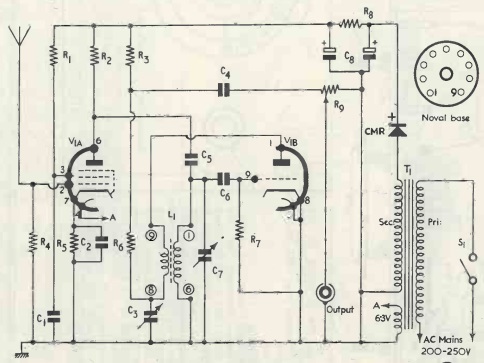

Sixty years ago this month, the September 1961 issue of the British magazine Radio Constructor carried the plans for this one-tube regenerative receiver covering 150 kHz through 28 MHz dubbed the “Finger-tip Five,” owing to the fact that it covered the range in five bands with five plug-in coils. While it did cover the longwave and mediumwave bands, it was especially designed for the shortwaves, “where much of interest is transmitted.”

Sixty years ago this month, the September 1961 issue of the British magazine Radio Constructor carried the plans for this one-tube regenerative receiver covering 150 kHz through 28 MHz dubbed the “Finger-tip Five,” owing to the fact that it covered the range in five bands with five plug-in coils. While it did cover the longwave and mediumwave bands, it was especially designed for the shortwaves, “where much of interest is transmitted.”