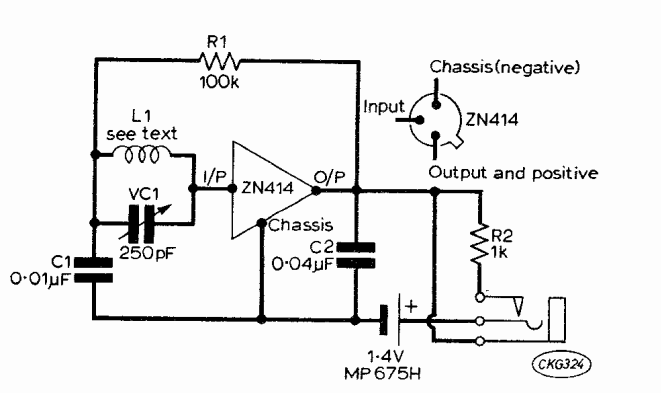

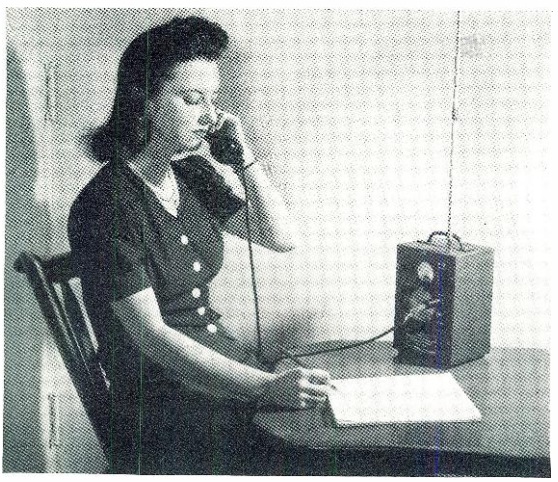

Fifty years ago, this British woman probably had the smallest radio receiver on her block, and she constructed it herself, thanks to the plans contained in the January 1973 issue of Popular Wireless. The set owed it’s diminutive size to then-revolutionary ZN414 integrated circuit, manufactured by Ferranti, which contained all of the circuitry for a tuned radio frequency (TRF) AM receiver onto a single chip. The chip’s specs covered long wave up to about 5 MHz, but in a prototype made by the magazine, the chip was able to cover the 49 meter shortwave band. The version shown in the magazine covered the medium wave band, but could be easily moved to different frequency ranges. For strong stations, the set sometimes tuned broadly, but when two stations were close together, it would separate them, even if one was strong.

Fifty years ago, this British woman probably had the smallest radio receiver on her block, and she constructed it herself, thanks to the plans contained in the January 1973 issue of Popular Wireless. The set owed it’s diminutive size to then-revolutionary ZN414 integrated circuit, manufactured by Ferranti, which contained all of the circuitry for a tuned radio frequency (TRF) AM receiver onto a single chip. The chip’s specs covered long wave up to about 5 MHz, but in a prototype made by the magazine, the chip was able to cover the 49 meter shortwave band. The version shown in the magazine covered the medium wave band, but could be easily moved to different frequency ranges. For strong stations, the set sometimes tuned broadly, but when two stations were close together, it would separate them, even if one was strong.

The small set had good sensitivity, and tuned in Radio Luxembourg loud and clear. Audio was through a crystal earphone. The case for the radio was a snuff container, which the author reported could be purchased for 9 pence (including the snuff). The author added that “if you haven’t tried snuff, this is your chance,” and that he was partial to the occasional pinch.

The ZN414, like most things, is available on eBay. But it’s replacement, the TA7642, is readily available for those seeking to duplicate this project.