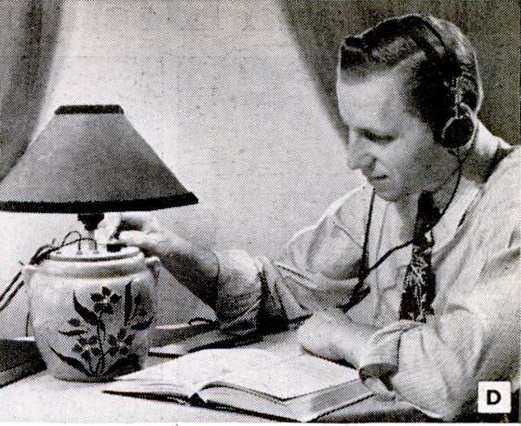

This gentleman is happy listening to his favorite program, but the rest of his family is also happy, because he is listening with headphones. This is because, according to the July 1949 issue of Popular Mechanics, the easy-to-build set is intended for “that member of the family who frequently wants to listen to radio programs whch are not particularly popular with the rest of the group.”

This gentleman is happy listening to his favorite program, but the rest of his family is also happy, because he is listening with headphones. This is because, according to the July 1949 issue of Popular Mechanics, the easy-to-build set is intended for “that member of the family who frequently wants to listen to radio programs whch are not particularly popular with the rest of the group.”

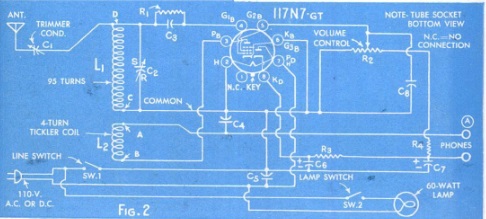

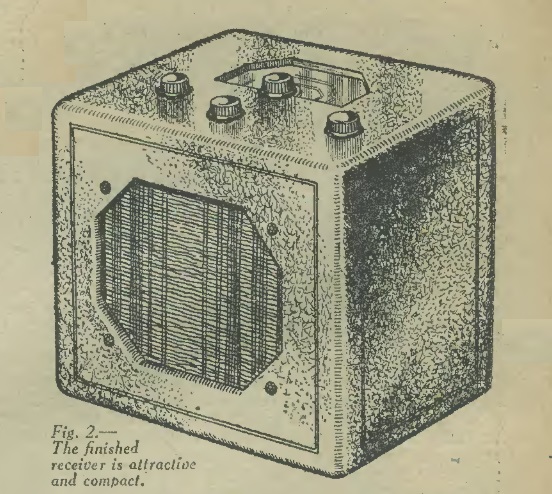

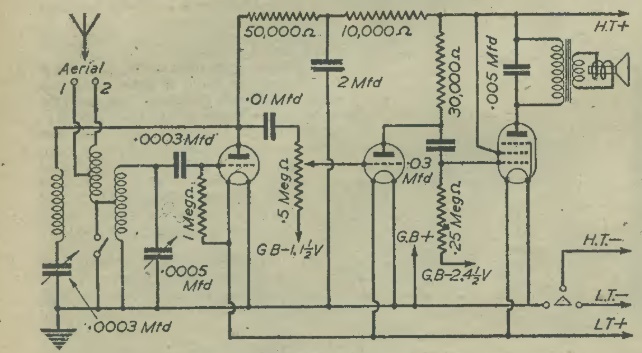

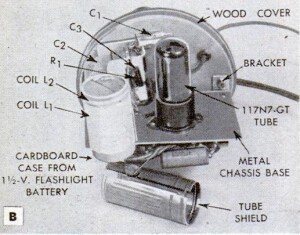

It’s conveniently built in to a cookie jar, and even includes a reading lamp. In many radio circuits incorporating a lightbulb, the lamp was there to drop the voltage for the filaments. But in this case, the lamp was there merely for lamp purposes, and was completely independent of the radio circuit, since the set used a 117N7GT tube, whose filament ran off the line voltage. One half of the tube served as rectifier, with the pentode section serving as regenerative detector.

With a piece of wire tossed on the floor, the set would pull in the local stations, and with a good outdoor antenna, it would bring in the distant stations with surprising volume and clarity.