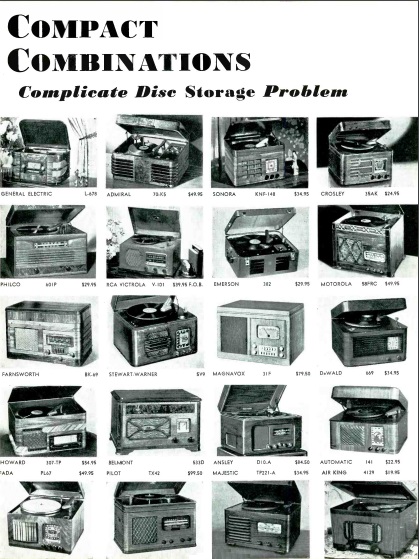

These girls are now close to 90 years old, but they undoubtedly had an appreciation for music their entire lives, thanks to their parents’ foresight in buying this model L-678 radio-phono from General Electric. They are shown here having a concert in their very own room thanks to the instrument. They were able to operate the set themselves, and the turntable could accommodate 12 inch records, even with the lid closed.

These girls are now close to 90 years old, but they undoubtedly had an appreciation for music their entire lives, thanks to their parents’ foresight in buying this model L-678 radio-phono from General Electric. They are shown here having a concert in their very own room thanks to the instrument. They were able to operate the set themselves, and the turntable could accommodate 12 inch records, even with the lid closed.

Their parents were able to find much of the world’s finest music especially arranged for children, allowing them a wonderful opportunity to develop an appreciation for good music. This set retailed for only $39.95. The ad also featured the model L-500 radio, “encased in handsome mahogany plastic cabinet that won the top award in the nation-wide Modern Plastics contest.” Also shown is the portable model JB-410, which the police officer notices and points out that he also has a GE radio in his squad car.

The ad appeared 80 years ago today in the March 10, 1941, issue of Life magazine.