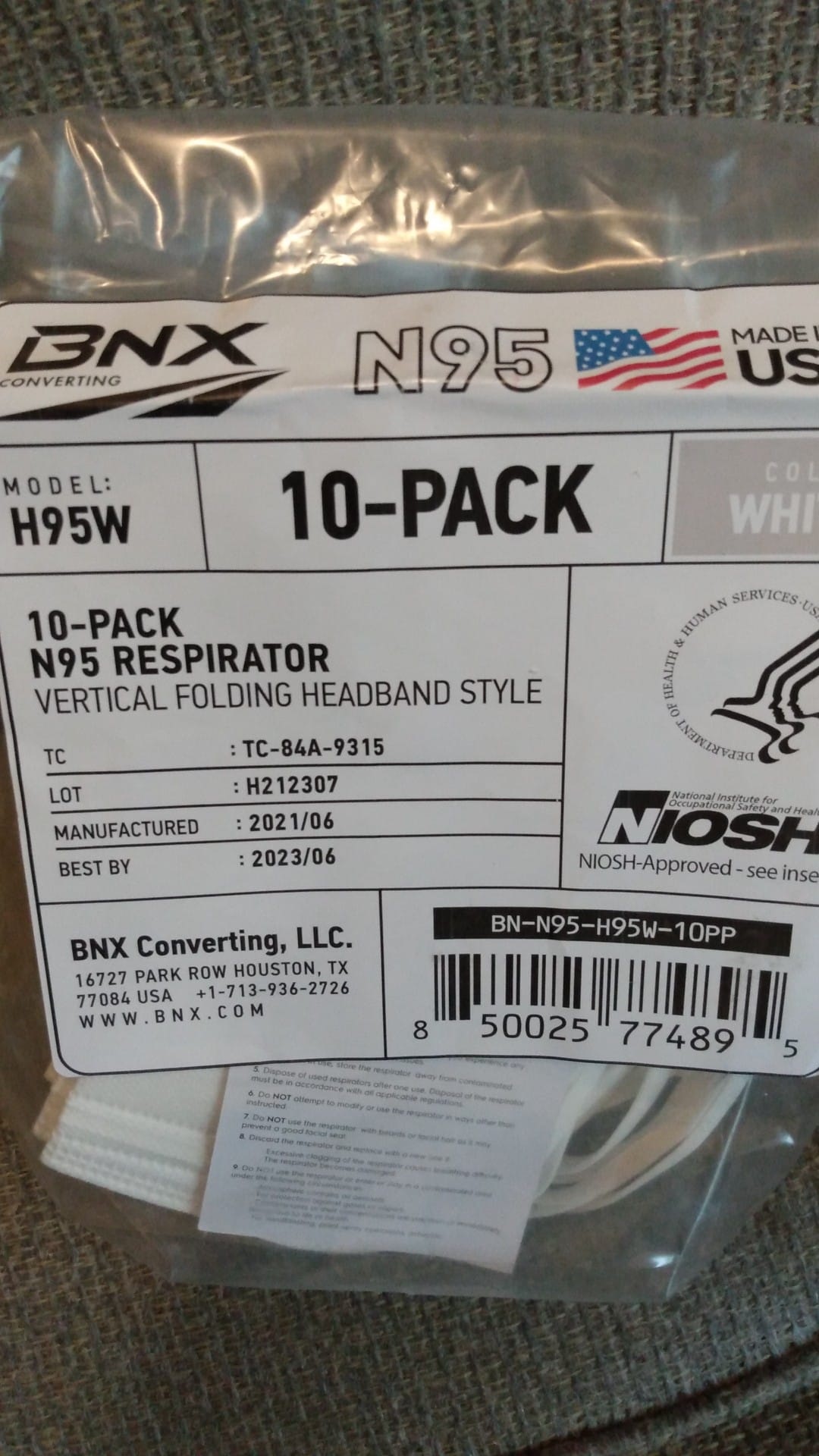

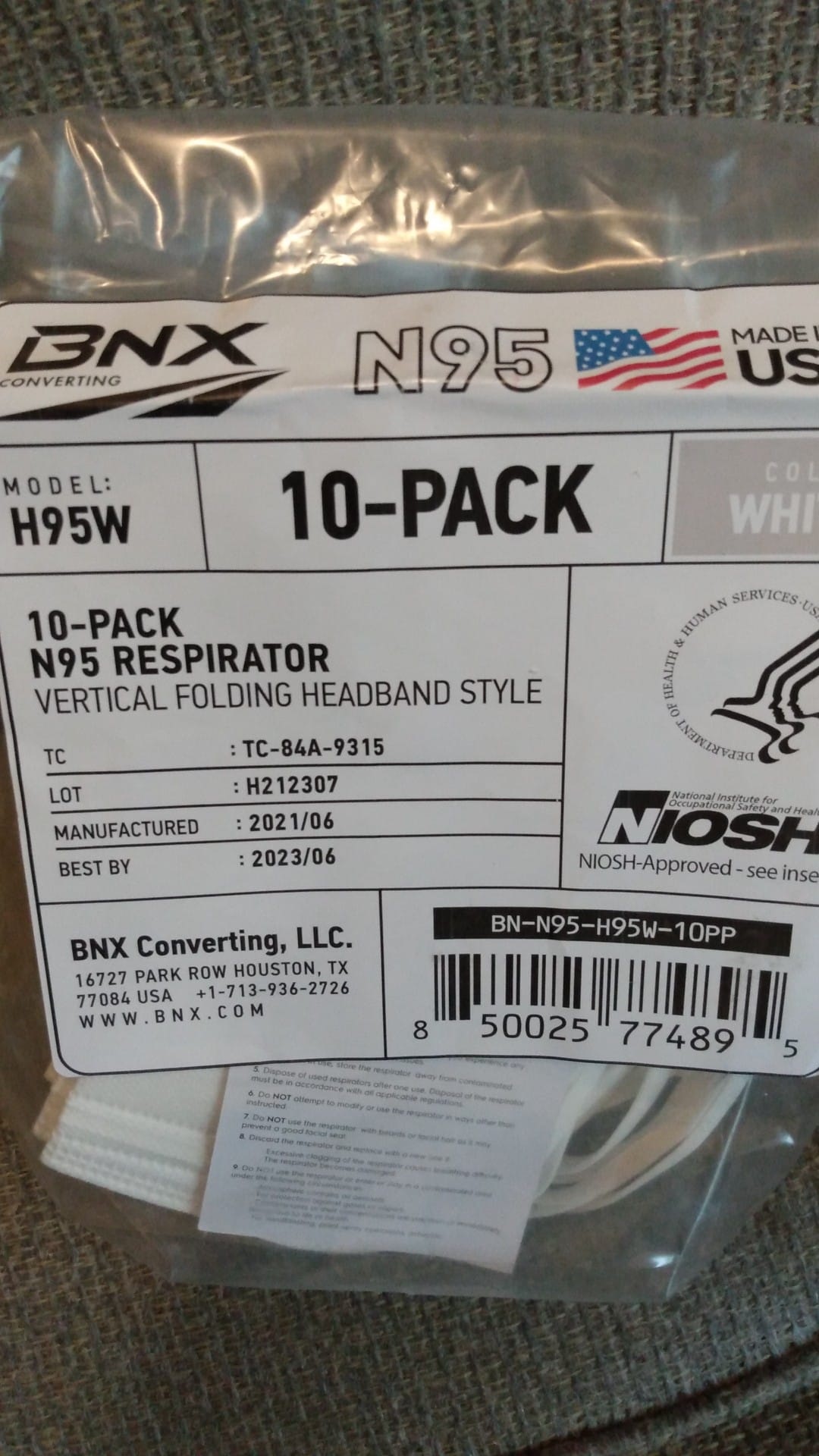

Bottom Line: The AccuMed BNX N95 mask is a high quality protective mask, meets USA N95 standards, and is made in the USA. Even if this pandemic is over, it’s worth keeping some on hand for the next public health emergency. Update 12/26/21: When this review was written, Amazon carried the 10 pack shown above. At this time, only the 50 pack is available in white. The other masks reviewed on this page are available in smaller quantities. Update 12/29/21: The 10 pack is available again in black at this link.

Quick Link

Preparing for Emergencies

I like to believe that I’m reasonably well prepared for emergencies, and the COVID-19 pandemic generally proved that I was prepared. We never ran out of toilet paper, although early on, we did have to be careful with our limited supply, and at one point we were rationing coffee. Curiously enough, the first thing we ran out of was lightbulbs, although we could have gotten by quite a bit longer by scrounging them from other rooms in the house. Even when riots hit the area, we were fully stocked with all the necessities of life, other than having to use powdered milk for a few days.

In a few cases, we had to make substitutions. We didn’t have very much hand sanitizer, but we solved that problem by washing our hands. And even though sanitizing wipes were unavailable, bleach was readily available and we were able to use it for sanitizing items.

But there was one shortage that made me angry at myself: In 2019, I could have walked into any hardware store to buy an N95 mask that was made in the USA. And unlike most people, I actually knew that an N95 mask would be a useful thing to have around in a public health emergency. But at the start of the pandemic, they were totally unavailable. And early on in the pandemic, we were told that it was practically unpatriotic to wear a mask, especially an N95 mask, because the limited supply was earmarked for healthcare workers.

A few weeks later, the official advice flip flopped, and we were told that it was unpatriotic not to wear a mask. But the N95 masks (in other words, the ones that were actually effective in preventing the spread of disease) were still off limits, since they were still reserved for healthcare workers.

During those early days of the pandemic, I rarely wore a mask, because I was rarely in a situation where I needed one. I didn’t go into other buildings, period. And I believed (and still do believe) that the risk outdoors was extremely small. I did all of my shopping with curbside pickup or home delivery. So I didn’t need a mask, because I wasn’t going into stores or other buildings.

The Need for a Good Mask

But eventually, there were unavoidable situations where I did need to go into buildings. So after about three months, despite the official guidance to the contrary, I decided it was time for me to be selfish and buy an N95 mask. Unfortunately, there were none to be had. The best I could find at that time was a KN95 mask, and even those were hard to find.

“N95” means that a mask meets the U.S. Government’s NIOSH standards. “KN95” means that the mask meets the standards of the Communist Chinese Government, and almost all of those masks were made in Communist China. The irony wasn’t lost on me: I was buying a Chinese Communist mask to protect myself against the Chinese Communist virus. I wasn’t happy about it, but I only had myself to blame. After all, in 2019, I could have walked into the hardware store and bought an American-made mask with the U.S. seal of approval. I didn’t do so, and I was stuck having to rely on the Communist Chinese Seal of Approval.

The mask I bought was the one shown at the left, and it served me very well. It was made in China, but it was imported by a reputable American company, AccuMed. At the time, there were a lot of dubious products on the market. I researched AccuMed and found that they were a medical supply company with an excellent reputation. Frankly, their name on the product meant more to me than the certification from some Chinese lab. The company was also in the process of gearing up to produce masks in the USA. (The same mask, made in the USA, is now available. Even though it is now made in the USA, it has the KN95 designation, probably because it uses ear loops instead of bands that go behind the head.) Those masks served me very well for a couple of months. On the occasions when I had to be inside the same building as other people, I was protected.

The mask I bought was the one shown at the left, and it served me very well. It was made in China, but it was imported by a reputable American company, AccuMed. At the time, there were a lot of dubious products on the market. I researched AccuMed and found that they were a medical supply company with an excellent reputation. Frankly, their name on the product meant more to me than the certification from some Chinese lab. The company was also in the process of gearing up to produce masks in the USA. (The same mask, made in the USA, is now available. Even though it is now made in the USA, it has the KN95 designation, probably because it uses ear loops instead of bands that go behind the head.) Those masks served me very well for a couple of months. On the occasions when I had to be inside the same building as other people, I was protected.

True to its promise, a few months later, AccuMed came out with a mask that was made in the USA, and I previously reviewed that mask, the duckbill-style A96 mask, similar to the one shown at left. This mask was made in the USA, but it was sold as meeting the Chinese KN95 standard, because the American N95 certification was still pending. It’s odd to have an American product that’s advertised as meeting the Chinese standard. But the virus doesn’t care about the paperwork. It was made in the USA by a reputable company, it seemed to form a tight seal, and I have no doubt that it provided protection. And after I purchased it, the mask was approved, and now has the U.S. N95 seal of approval.

True to its promise, a few months later, AccuMed came out with a mask that was made in the USA, and I previously reviewed that mask, the duckbill-style A96 mask, similar to the one shown at left. This mask was made in the USA, but it was sold as meeting the Chinese KN95 standard, because the American N95 certification was still pending. It’s odd to have an American product that’s advertised as meeting the Chinese standard. But the virus doesn’t care about the paperwork. It was made in the USA by a reputable company, it seemed to form a tight seal, and I have no doubt that it provided protection. And after I purchased it, the mask was approved, and now has the U.S. N95 seal of approval.

Edited to add (11/16/21): The AccuMed A96 no longer appears to be available on Amazon, but this Kimberly Clark N95 mask, shown at left, appears to be identical.

This mask, like most N95 masks, was a bit more difficult to put on than the KN95 mask, because the elastic goes around the back of the head, and not just over the ears. But even though it’s slightly harder to put on, it’s much more comfortable to wear, since it’s not constantly pulling on your ears. If I had to wear a mask all day, this would be a huge advantage.

The New Made in USA N95 Mask

Fortunately, the time has now come when it’s once again possible to buy the thing that I should have bought in 2019: An N95 mask made in the USA, the BNX N95 Mask NIOSH Certified MADE IN USA Particulate Respirator Protective Face Mask. I recently received mine, and I’m glad to have it.

Fortunately, the time has now come when it’s once again possible to buy the thing that I should have bought in 2019: An N95 mask made in the USA, the BNX N95 Mask NIOSH Certified MADE IN USA Particulate Respirator Protective Face Mask. I recently received mine, and I’m glad to have it.

Like most other N95 masks, the straps go around the head, which makes it slightly more difficult to put on. But the advantage is that it’s much more comfortable once you have it on. It seems to form a good seal. If I had to work for hours with this mask on, it would cause very little if any discomfort.

Both of the AccuMed N95 masks, the white one and the blue duckbill style one, are comfortable to wear, and both make a good seal. For me, the white one is a little easier to put on, although the blue one seems to be easier to ensure a good seal once it’s on my face. Either one, though, takes only seconds to put on. One thing to keep in mind, though, is that the blue one seems to fit better on a smaller head. My daughter had a hard time getting a good seal with the white mask, but it was much easier with the blue mask. So if you are buying for a family, I would recommend getting both.

On the other hand, I now rarely have to wear a mask for more than a few minutes. Therefore, I will probably continue to use the AccuMed KN95 mask in those situations. It seems to have a good seal, and if I’m just going into the store for a few minutes, it’s somewhat more convenient to put on.

Especially at the beginning of the pandemic, and probably still now, there were a lot of fake masks hitting the market, and it’s important to buy from a reputable source. Fortunately, AccuMed/BNX is a real company, selling a real product, from a real bricks and mortar location in Houston, Texas, shown here. You can probably find something cheaper at the dollar store, but it’s more important to buy something that will really protect you, rather than trying to save a few pennies.

Especially at the beginning of the pandemic, and probably still now, there were a lot of fake masks hitting the market, and it’s important to buy from a reputable source. Fortunately, AccuMed/BNX is a real company, selling a real product, from a real bricks and mortar location in Houston, Texas, shown here. You can probably find something cheaper at the dollar store, but it’s more important to buy something that will really protect you, rather than trying to save a few pennies.

Ongoing need for a mask

From my personal point of view, the pandemic ended on March 15, 2021. On that date, the immunity from my second dose of the Moderna vaccine officially kicked in. There’s still a possibility that I’ll be infected, but the risk of serious illness or death are practically nil. The day after my immunity kicked in, I went from never going inside buildings unless absolutely necessary, to taking teaching jobs which put me in close contact with hundreds of kids. (I secured an early dose of the vaccine as a teacher, and I felt it was my duty to resume teaching at the earliest possible moment.) In my opinion, the need for a mask is now mostly gone. Chances are, I will rarely wear the new N95 mask. Because it was required this school year, I wore a mostly symbolic cloth mask while teaching. With my vaccination, I didn’t feel the need to wear the N95 mask all day. But if I had to work close to other people and was not yet vaccinated, I would certainly wear one of the N95 masks.

Even though I don’t believe it’s is necessary because of the vaccine, I have noticed that I didn’t get any colds or flu during the pandemic lockdown, because I wasn’t in a position to be infected. On my first few trips back to Walmart after a long absence, I realized something: There was a certain amount of truth to all of those “People of Walmart” memes. Many of my fellow shoppers don’t look particularly healthy. They might not be infections with COVID-19, but it’s likely that they’re infectious with something. Wearing a mask for my own protection probably isn’t a bad idea, and since I have some of them, I’ll probably slip on the KN95 mask before going in there or similar environments.

Even though all of my masks are disposable, there’s no reason why they can’t be used many times. I store mine in a paper bag labeled with the date. I have links to official guidance on reuse of masks at my earlier review. So when you order your masks, don’t forget to order a supply of brown paper bags.

Even though all of my masks are disposable, there’s no reason why they can’t be used many times. I store mine in a paper bag labeled with the date. I have links to official guidance on reuse of masks at my earlier review. So when you order your masks, don’t forget to order a supply of brown paper bags.

At this point, I no longer have an immediate need for an N95 mask. From my point of view, the pandemic is over, because I am vaccinated. However, I didn’t need an N95 mask in 2019, and I’m still kicking myself for not going to the hardware store and buying one then. It would have made the early months of the pandemic less stressful knowing that I had this supply if needed.

And the next pandemic might be worse, and during that pandemic, I might need to come into contact with other persons. Even though it proved deadly to many, coronavirus was not as lethal as many anticipated. But the next plague might be worse. Having an N95 mask on hand for such an emergency is a low-cost way to make sure I’m prepared. I hope I never have to use them, just like I hope I never have to use my potassium iodide. But I feel a lot better knowing I have them.

During this pandemic, I never ran out of toilet paper. And in the next pandemic, I won’t run out of N95 masks, because I bought some when they were still available. I’m not making the same mistake I made in 2019.

I recommend all three of these masks. The duckbill style mask in the middle seems to be slightly easier to get a good seal, although it’s slightly more difficult to put on in the first place. If necessary, it would be comfortable enough to wear all day. Of the three, it probably is the best choice for children.

The white mask on the left is slightly easier to put on, and would also be a good mask if needed for all day use.

The white mask on the right seems to be very good quality, although it does not have the U.S. N95 approval. It is made in the USA, but has the Chinese KN95 approval. The reason is probably the fact that it uses ear loops rather than head bands. It is the easiest to put on, but the ear bands would be uncomfortable for all day use. It’s the easiest to use if you have to go into a store for a few minutes.

Since they all have slightly different uses, I’m glad I have a supply of all three for the next pandemic.

The product was supplied at no charge by the manufacturer in exchange for an honest review. Some links on this page are affiliate links, meaning that this site earns a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking on the link.

Most N95 respirators are intended to be disposed of after a single use. However, during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, there were insufficient numbers of respirators for healthcare workers, and strategies for preserving the supplies were necessary. Therefore, the Centers for Disease Control published strategies for reusing masks, rather than disposing of them after each use. Those strategies were published online.