Quick links:

Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.

–Herodotus, as carved in stone at the New York Post Office.

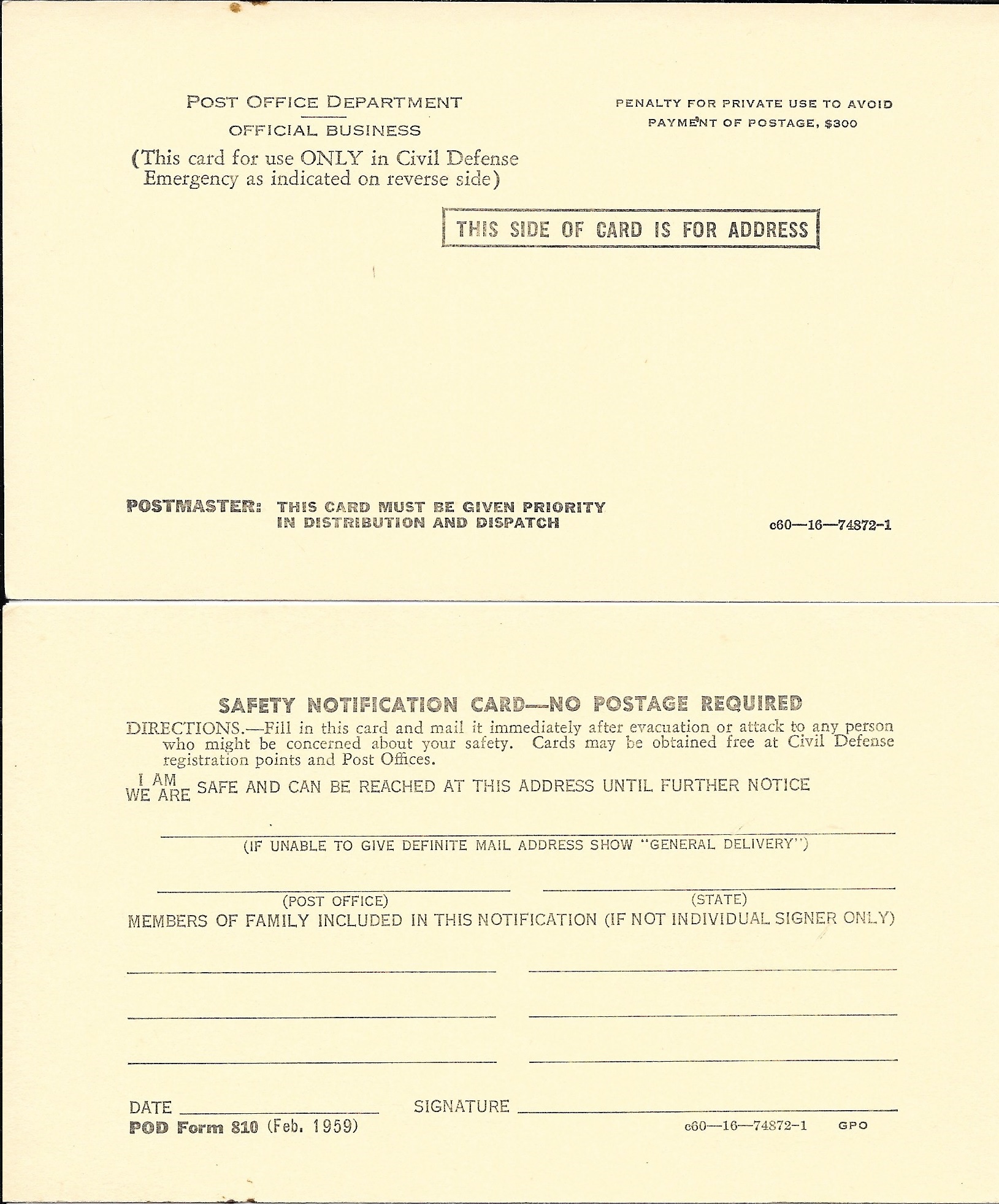

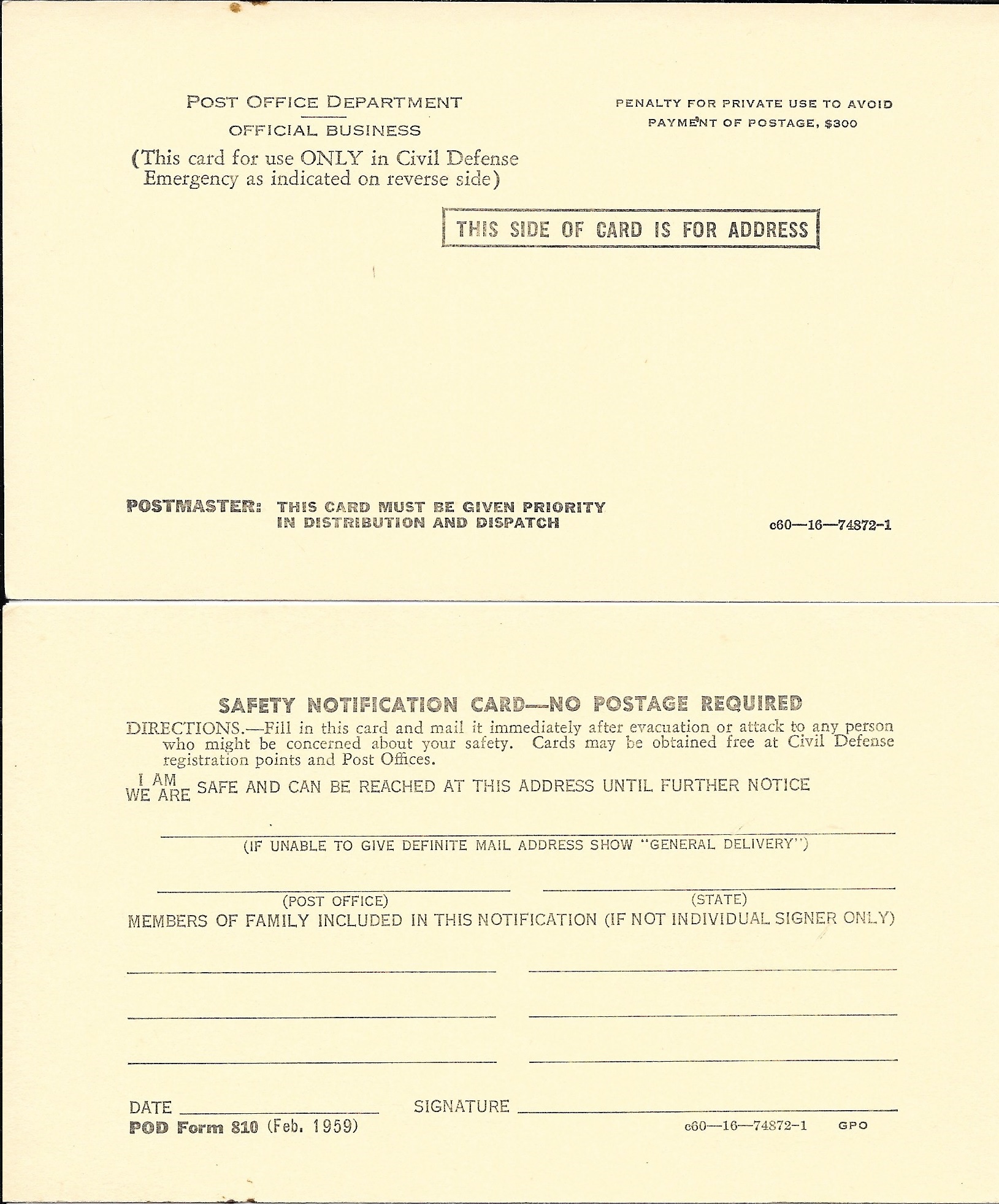

The postcard shown above, first issued in 1959, and current for at least two decades thereafter, was a Safety Notification Card (Post Office Department form 810), for use after a civil defense emergency such as a nuclear war. After such an event, the Post Office would be tasked with putting friends and relatives back in touch with one another. On the front of the card, you would write the name and address of those who might be worried about you. On the back, you would sign your name and give the address where you could be reached.

The postcard shown above, first issued in 1959, and current for at least two decades thereafter, was a Safety Notification Card (Post Office Department form 810), for use after a civil defense emergency such as a nuclear war. After such an event, the Post Office would be tasked with putting friends and relatives back in touch with one another. On the front of the card, you would write the name and address of those who might be worried about you. On the back, you would sign your name and give the address where you could be reached.

I have no doubt that after Americans emerged from their fallout shelters, the Post Office would use Herculean efforts to deliver these cards, and most of them would go through. The Post Office is one of the things that makes us a country, and thus one of the things over which such a war would have been fought. It’s unthinkable that they would bother with fighting a nuclear war and then decide not to deliver the mail. Under the Constitution, the Congress has the power and duty to establish a Post Office, and a nuclear war doesn’t change that. Neither does a pandemic virus. With very few exceptions, the mails right now continue to flow without interruption during the lockdown. And most of the exceptions come from things outside the control of the U.S. Postal Service. For example, mail service is currently suspended to over a hundred countries, due either to lack of transportation or a shutdown of postal service in the destination country. But the U.S. Postal Service is doing whatever needs to be done to make sure the mail goes through. Even though most international mail has been by air for the past few decades, suspension of flights has prompted the U.S. Postal Service to send mail to Europe by container ship.

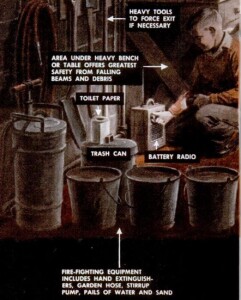

I have no doubt that after Americans emerged from their fallout shelters, the Post Office would use Herculean efforts to deliver these cards, and most of them would go through. The Post Office is one of the things that makes us a country, and thus one of the things over which such a war would have been fought. It’s unthinkable that they would bother with fighting a nuclear war and then decide not to deliver the mail. Under the Constitution, the Congress has the power and duty to establish a Post Office, and a nuclear war doesn’t change that. Neither does a pandemic virus. With very few exceptions, the mails right now continue to flow without interruption during the lockdown. And most of the exceptions come from things outside the control of the U.S. Postal Service. For example, mail service is currently suspended to over a hundred countries, due either to lack of transportation or a shutdown of postal service in the destination country. But the U.S. Postal Service is doing whatever needs to be done to make sure the mail goes through. Even though most international mail has been by air for the past few decades, suspension of flights has prompted the U.S. Postal Service to send mail to Europe by container ship.

In my experience, domestic mail is going through with little delay. I have a forwarding order to have all of my office mail to go to my home, and even forwarded items are arriving, at most, a day or two later than I would have expected them. The postal workers and letter carriers are working hard, and in many cases risking their lives to make sure the mail goes through. Would they have risked their lives delivering post cards across a nuclear battlefield? I have little doubt that they would have. (Say, that might make a good book.)

In my experience, domestic mail is going through with little delay. I have a forwarding order to have all of my office mail to go to my home, and even forwarded items are arriving, at most, a day or two later than I would have expected them. The postal workers and letter carriers are working hard, and in many cases risking their lives to make sure the mail goes through. Would they have risked their lives delivering post cards across a nuclear battlefield? I have little doubt that they would have. (Say, that might make a good book.)

Much of my work involves getting and sending things in the mail. And with the national emergency, the mail also serves as one of the ways that vital supplies arrive at our house. Yes, some of our food comes by mail.

One practical issue, however, is buying postage. In the pre-COVID time, I had to go to the post office frequently, and when the line was short, I picked up a few weeks’ supply of stamps. Sometimes, I would mail items at the counter, but I would usually just weigh them myself and affix the exact amount of postage required. (If you don’t have a scale, they’re not expensive.) Little has changed in that regard, since I can just leave outgoing mail for the carrier. But getting stamps has become more difficult.

One practical issue, however, is buying postage. In the pre-COVID time, I had to go to the post office frequently, and when the line was short, I picked up a few weeks’ supply of stamps. Sometimes, I would mail items at the counter, but I would usually just weigh them myself and affix the exact amount of postage required. (If you don’t have a scale, they’re not expensive.) Little has changed in that regard, since I can just leave outgoing mail for the carrier. But getting stamps has become more difficult.

Buying stamps online

At first, I ordered stamps online at the USPS website. Orders are fulfilled at a central location in Kansas City. At first, it worked well, and stamps and stamped envelopes arrived about a week after I ordered them. All denominations are available, and they’re sold at face value with only a small shipping charge. But the most recent order took 2-1/2 weeks. They’re obviously swamped in Kansas City, I was almost out of stamps, and had to come up with another way of getting them. Update: The last few orders have gone smoothly, and the stamps arrive within about 10 days.

Curbside stamp pickup

I did find three sources locally that have curbside pickup. Office Depot has stamps, at face value. You can buy a book of 20 Forever stamps for $11. Unfortunately, the closest one was out of stock, and other stores looked like they had low stocks. Update: Since I originally wrote this, Office Depot is doing an excellent job of keeping stamps in stock. You can usually order online and pick them up curbside the same day. Walgreens also sells stamps at face value. You can order online and pick them up, usually in about an hour, either curbside or at the drive-up window. It looks like CVS has curbside pickup of stamps in some states, although I don’t know if they are being sold at face value.

Printing postage at home

Another great option is OrangeMailer.co which allows you to buy postage online and print it with your printer. I was leery about using them, since I imagined my printer jamming and having to pay again. Fortunately, that is not the case. You can print as many times as necessary until you get it right. Of course, if you use more than one of those prints for postage, you’ll be spending some time in Leavenworth.

Another great option is OrangeMailer.co which allows you to buy postage online and print it with your printer. I was leery about using them, since I imagined my printer jamming and having to pay again. Fortunately, that is not the case. You can print as many times as necessary until you get it right. Of course, if you use more than one of those prints for postage, you’ll be spending some time in Leavenworth.

To buy postage, you enter the name and address of the recipient, and when you’re done, the website directs you to turn on your printer and print a label with the address, your return address, and the postage meter. For letters, you can print right on the envelope. It took me a couple of tries with my printer settings to get it exactly right. The first few times, it cut off my return address. When I told my printer that it was printing a number 10 envelope, it cut off the return address. But when I lied and told the printer that it was a 4 by 8 sheet of paper, it worked perfectly. Similarly, for small envelopes, I have to tell the printer that it’s a 4 by 6 piece of paper.

I have also mailed one small package, and that works well. You enter the dimensions and weight of the parcel, and it prints a label with the right amount of postage. Of course, we don’t have any labels in the house, but you don’t need any. I used a plain sheet of paper and affixed it to the package with Scotch tape. One advantage for packages is that if a package is over 13 ounces, you can’t use stamps. But printing the postage online is equivalent to taking it to the counter at the Post Office.

The philatelist in me likes using real stamps. And it’s faster to just scribble the address and slap on a stamp. But given the current emergency, OrangeMailer.co is an extremely convenient option. Unlike their largest competitor, there is no monthly charge. You just have to deposit a minimum of $10, enough for 18 First Class letters. You pay the customary postage of 55 cents per letter. They make their 5 cent profit due to the fact that your metered letter is actually going for only 50 cents. That seems reasonable to me.

Other online sources

If you do need actual stamps, two other options appear to be faster than ordering directly from the USPS. You’ll pay more than face value, but not a great deal more. If you combine the purchase with another order, you can get free shipping. You can buy postage stamps on Amazon for only a little over face value. If you do a search for “postage stamps,” click the button for “free shipping by Amazon,” and you’ll see the ones that can be added to another order. As long as the total order is at least $25, there will be no shipping charge.

If you do need actual stamps, two other options appear to be faster than ordering directly from the USPS. You’ll pay more than face value, but not a great deal more. If you combine the purchase with another order, you can get free shipping. You can buy postage stamps on Amazon for only a little over face value. If you do a search for “postage stamps,” click the button for “free shipping by Amazon,” and you’ll see the ones that can be added to another order. As long as the total order is at least $25, there will be no shipping charge.

Walmart also sells stamps online, only slightly above face value, with free two-day shipping with a $35 order.

Some links on this page are affiliate links, meaning that this site earns a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking the link.

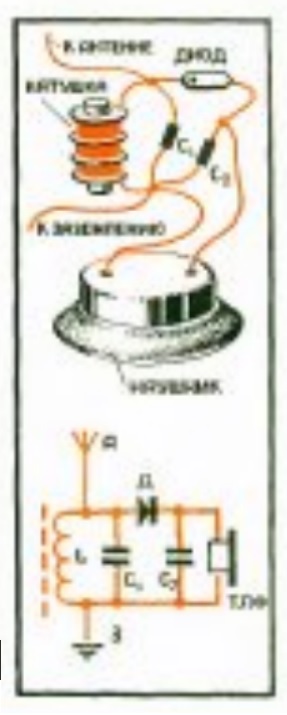

I’m not sure exactly what’s going on in this illustration, but the young comrade seems to be having a good time, even though both the tree and the bird are rather distressed.

I’m not sure exactly what’s going on in this illustration, but the young comrade seems to be having a good time, even though both the tree and the bird are rather distressed.