In three of the experiments, the stress level was increased by periodically playing simulated emergency broadcast system messages. The script of those broadcasts is particularly interesting, since it gives an insight into what civil defense planners thought might be a plausible scenario for a nuclear attack on the United States, and how news would be communicated to the public.

Here is the text of the nineteen radio broadcasts that might have been heard during a nuclear war:

EMERGENCY BROADCAST SYSTEM SCRIPT

EBS #1, Friday, 7:00 PM

ATTENTION. ATTENTION. This is the Emergency Broadcast System. Take shelter immediately. Take shelter immediately. This is not a drill.

Repeat: This is not a drill. An enemy attack is being launched against

the United States. Take shelter immediately and stay tuned to this

frequency for further instructions.

THE ABOVE MESSAGE IS TO BE REPEATED THREE TIMES, WITH 15-SECOND INTERVALS.

EBS #2, Friday, 7:10 PM

ATTENTION. ATTENTION. This is the Emergency Broadcast System. We have just been informed that the city is now on the emergency power system. Please inform the control center if your shelter is without light-., Repeat: The city is now on the emergency power system. Please inform the control center if your shelter is without lights. We also have ….. we also have word here that there has been no confirmed report of a missile strike in this area. There has been no confirmed report of a missile strike in this area.

EBS #3, Friday, 7:15

(Phone is heard ringing in background.)

ATTENTION. ATTENTION. This Is the Emergency Broadcast System. A missile attack has been launched against the United States. Reports about the attack are fragmentary and unconfirmed. The strategic missile bases west of the Mississippi appear to have borne the brunt of the attack. As of this moment there has been no official report of a nuclear detonation in our immediate vicinity. Fallout has begun to descend on the western portions of our city and is expected in other areas imminently. Do not communicate with the emergency operations center unless absolutely necessary.

.

EBS #4, Friday, 8:00 PM

ATTENTION. ATTENTION. This is the Emergency Broadcast System. Stay tuned for an important message. (DISTANT VOICE: Okay, stand by now. We’ve got a remote from Washington.) Static ——- Noise. Another voice: This is a report from the emergency national command post in Washington. The President and his key civilian and military aides have been safely evacuated to the emergency seat of government. This evening at 6:35 PM the enemy launched an attack against the strategic retaliatory forces of the United States and its NATO allies. An intelligence warning allowed us to launch a portion of our land-based missile force against the enemy’s remaining strategic forces.

Polaris missiles have also been launched. In addition, our airborne alert and a portion of our ground alert aircraft forces have been sent against the enemy’s non-missile strategic forces. Our damage assessment reports indicate that many of our SAC bases have been destroyed or severely damaged. A number of communities near SAC bases have also suffered great damage. The fallout monitoring network reports that radiation is heavy in the western portion of our country and is increasing in the midwest and eastern portions of our nation. Although there have been several nuclear detonations in the east, it appears as if these have been the result of errant missiles, rather than a planned attack against population centers. The President, whom, I repeat is alive and well, will address the nation as soon as his command duties permit. This is the end of the Priority One report. Local EBS stations may resume Priority Two broadcasting.

EBS #5, Friday, 8:30 PM

ATTENTION. ATTENTION. This is the Emergency Broadcast System. Short wave monitoring has disclosed that our air strike forces are currently launching attacks on the enemy homeland. These forces are utilizing a new….. what? What do you mean it’s not for release? (Another voice: Priority One. Now.. for heaven’s sake! Announcer: Well what the hell …… 1)

THIS MATERIAL CUT OUT.

EBS #6, Friday, 8: 50 PM

Has this one been cleared?

ATTENTION. ATTENTION. This is the Emergency Broadcast System. We have Just received word that the President has been evacuated to sea in the floating Whitehouse. The location of this ship is unknown. The floating Whitehouse is a battle cruiser, fully equipped for command and control functions. Our government has survived the attack. I repeat, our government has survived the attack.

EBS #7, Friday, 9:30 PM

ATTENION. ATTENTION. This is the Emergency Broadcast System, We have just been informed that a message is to be delivered from the governor’s office in Harrisburg. Please stand by,

This is a report from the governor’s office in Harrisburg. The state of

conditions in Pennsylvania is serious, but not critical. Erie has been

severely damaged by what is believed to have been a stray missile. No other cities have reported being hit, but the fallout level is rapidly increasing, particularly in western Pennsylvania. Apparently neighboring states have borne the brunt of the attack, particularly those in the western portions of the country. All citizens should seek shelter immediately. Do not attempt to evacuate your area until you are instructed to do so. Local law enforcement personnel should remain in their respective areas. State police have been assigned to more critical areas, and additional state aid will become available and be assigned when fallout levels permit.

EBS #8, Friday, 10:15 PM

ATTENTION. ATTENTION. This is the Emergency Broadcast System. Fallout began to descend on the Pittsburgh area several hours ago and radiological monitoring reports indicate that radiation levels are dangerously high in many parts of our city. No one should attempt to leave shelters. Repeat: No one should attempt to leave shelters. Youngstown, Ohio and Erie, Pennsylvania have suffered severe damage as a result of nuclear detonations.

As of the moment there have been no nuclear blasts in our immediate area. The municipal power has been temporarily disrupted in some parts of the city. Power should be restored shortly. No further official reports on our retaliatory attacks on the enemy homeland are available. Unofficially, the absence of any significant second wave of enemy attack, plus the size of our surviving strategic force, allows cautious optimism that we will suffer no further major damage from any attack. Until further word is transmitted by this station, everyone must remain in shelters.

EBS #9, Friday, 10:30 PM

ATTENTION. ATIENTION. This is the Emergency Broadcast System. In order to evaluate the damage to Pittsburgh, the emergency operations center requests every shelter to gather the following information and to report it to the local emergency operations center. Is this a fallout or a blast shelter? How many persons are in the shelter? How many of these persons are injured? How many persons are suffering from radiation sickness? What is the condition, of your equipment? Is your shelter structure damaged? Do you have adequate electricity?

Do you have adequate ventilation? What is the state of your food supplies? What is the state of your water supply? Do you have any illness other than radiation sickness? As soon as we have received reports from district control centers we will relay such information on to you. When emergency missions are possible, disaster teams will be sent to those shelters which need medical supplies, food and water. Attempts will also be made to report specific areas of damage in our city. Please stay tuned for additional announcements.

EBS #10, 11:30 PM

ATTENTION. ATTENTION. This is the Emergency Broadcast System. Wee have hundreds of people in the area who do not have shelter with an adequate protection factor. They must be moved to other shelters in order to survive.

Please advise the emergency operations center as to the number of additional people you can take into your shelter. This is imperative. Please inform the emergency operations center as to the number of additional people you can take into your shelter.

EBS #11, Saturday. 1:30 AM

ATTENTION. ATTENTION. This is the Emergency 3roadcast System. Radiological monitoring teams report that the radiation levels in the Pittsburgh area are still high. However, there is no additional accumulation of radioactive dust. The fallout on the ground is beginning to decay. It is simply a matter of waiting out this decay time before we can undertake further civil defense measures. Everyone is to remain inside until further notice. Please do not leave your shelters.

EBS #12, Saturday, 2:15 AM

ACCIDENTALLY OVERHEAR A SHORT WAVE BROADCAST. “Hello Tower…. to checkpoint two…. ” Static and short wave noise.

EBS #13, Saturday, 3:00 AM

LOUD STATIC AND SHORT WAVE NOISE.

ATTENTION. ATTENTION. This is the Emergency Broadcast System.

EBS #14, Saturday, 3:45 AM

ATTENTION. ATTENTION. This is the Emergency Broadcast System. Reports have been received that there are bands of looters wandering about the city. Attempts have been made to loot shelters in this area. Be alert to this situation and act accordingly. Security police will begin patrolling the area as soon as the radiation level permits.

EBS #15, Saturday, 4:15 AM

ACCIDENTALLY OVERHEAR SAC PLANE MESSAGE. Sounds like:

“Angels 46 — Same heading — Roger, Angels 52 — Fuel 30 … ”

Much static.

EBS #16, Saturday, 6:00 AM

ATTENTION. ATTENTION. This is the Emergency Broadcast Svytem. Stay tuned for an important message. Okay, stand by to switch.

MUCH STATIC ———– “Please stand by.”

This is a Priority One report from the emergency national command post in Washington. It appears that the enemy attack is over. There have been no further reports of missile strikes since early last evening. Radio monitoring indicates no further enemy air activity. Damage assessment reports indicate that the brunt of this attack was borne by western states. Many of our SAC bases have been destroyed or severely damaged. Communities near SAC bases have also been severely damaged. The central and eastern portions of the country have escaped extensive damage although stray missiles have struck some of the smaller population centers. Fallout is moving across the country in an easterly direction, carried on westerly winds. All citizens should remain in shelters until instructed otherwise by local civil defense commands. The President and key members of his cabinet are still aboard the U. S. S. Northampton. The President will address the American people as soon as his command duties permit.

This is the end of the priority ….. this is the end of the Priority One report. Local EBS stations may resume priority two broadcasting.

EBS #17, Saturday, 7:30 AM

ATTENTION. ATTENTION. This is the Emergency Broadcast System. Emergency teams have been established and have begun to operate in various sections of Pittsburgh. There is a shortage of able-bodied men to serve on work details in Shadyside, East Liberty, Bloomnfield, and Morningside. Will all shelters submit to the emergency operations center the names of able-bodied volunteers who may be asked to leave shelters before radiation levels are completely safe for permanent exit. Phone the names into the emergency operations center. Further information will be provided as to when and where the rescue volunteers will report.

EBS #18, Saturday. 10:00 AM

ATTENTION. ATTENTION. This is the Emergency Broadcast System. Weather monitoring teams report that there is a severe storm approaching the Pittsburgh area. What’s that? It appears that this storm is bearing with it a radioactive dust cloud and we expect the levels of radiation to increase severely. Some shelters do not have adequate protection facilities against this cloud. There is a possibility that some shelters will have to mobilize and be moved. (PAUSE) We will contact these shelters by phone within the next few minutes. Please do not call the emergency operations center. If your shelter is one of these that has to be mobilized and be moved, we will contact you. Please stand by.

EBS #19, Saturday 3:00 PM

ATTENTION. ATTENTION. This is the Emergency Broadcast System. Radiological calculations of fallout levels in Pittsburgh indicate that permanent exit from some shelters will be possible in the near future. At the present time recovery teams are surveying the city to locate and to prepare facilities for post-shelter operations. It is imperative that you do not attempt to leave your shelter without prior notice from the emergency operations center. There are still many dangerous radiological “hot spots” in the city. Therefore, regardless of the radiological readings in your immediate vicinity, wait for official notification. from your government in the emergency operations center.

THE END

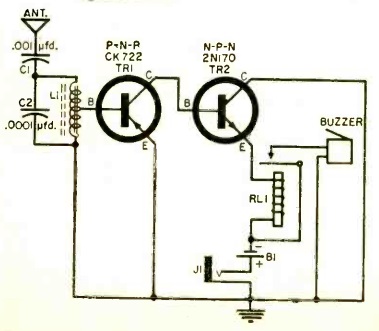

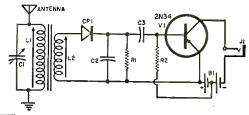

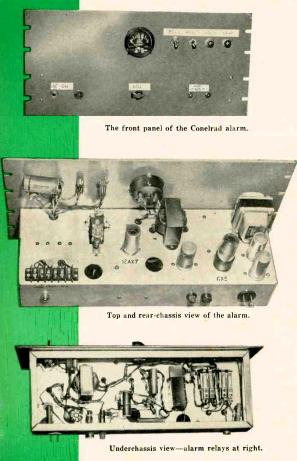

From 1951-1963, U.S. broadcast stations were required to participate in CONELRAD, a system designed to alert the public to enemy attack, but also deprive enemy bombers of radio signals which could be used for navigation purposes. Under a CONELRAD alert, all stations would cease broadcasting on their normal frequencies. Designated stations would switch to broadcasting on either 640 or 1240 kHz. The result would be that listeners would be able to hear alerts, but enemy bombers would hear only a confusing jumble of signals on those frequencies.

From 1951-1963, U.S. broadcast stations were required to participate in CONELRAD, a system designed to alert the public to enemy attack, but also deprive enemy bombers of radio signals which could be used for navigation purposes. Under a CONELRAD alert, all stations would cease broadcasting on their normal frequencies. Designated stations would switch to broadcasting on either 640 or 1240 kHz. The result would be that listeners would be able to hear alerts, but enemy bombers would hear only a confusing jumble of signals on those frequencies.![]()