Shown here in the June 1943 issue of QST are students at Northbridge Senior and Junior High Schools, Whitinsville, Mass., learning Morse Code under the tutelage of assistant principal James Perkins Saunders, W1BDV.

Shown here in the June 1943 issue of QST are students at Northbridge Senior and Junior High Schools, Whitinsville, Mass., learning Morse Code under the tutelage of assistant principal James Perkins Saunders, W1BDV.

Before the War, there had been some instruction in radio for interested students, but it had consisted mostly of informal coaching of students interested in obtaining their ham licenses. But with war, radio became a vital skill, and the school vigorously undertook pre-induction training in the radio arts, including both theory and Morse Code.

To accommodate code training, the school’s schedule was adjusted. Two minutes were shaved off each of the seven class periods, and the lunch period was reduced by one minute. This allowed the time period from 8:05 to 8:20 AM to be set aside exclusively for code practice. Each day, Saunders manned the key in the school office, as shown here, and code was piped throughout the building. Later, a tape machine was procured, and Army-Navy code training tapes were played. A student assistant monitored the tapes and copied along, and at the end of the session, he read back the text that had been sent.

To accommodate code training, the school’s schedule was adjusted. Two minutes were shaved off each of the seven class periods, and the lunch period was reduced by one minute. This allowed the time period from 8:05 to 8:20 AM to be set aside exclusively for code practice. Each day, Saunders manned the key in the school office, as shown here, and code was piped throughout the building. Later, a tape machine was procured, and Army-Navy code training tapes were played. A student assistant monitored the tapes and copied along, and at the end of the session, he read back the text that had been sent.

The code training was intended primarily for students in the high school, but since the P.A. system was shared with the junior high, the younger students were also encouraged to participate.

Participation was optional, and some students used the period as a study hall. Initially, 250 students were participating, but this number dropped to 75 at the end of the term. Each week, a test was given, and teachers sent the classroom’s copy to the office for scoring. At the start of the next term, the program again started from scratch, with advanced students moving on to a dedicated 45 minute class.

The typing class, shown here, was conducted by Saunders one day a week. Instead of their normal typing lesson, the students listened to code being sent by Saunders, and they learned to copy on the “mill”.

The typing class, shown here, was conducted by Saunders one day a week. Instead of their normal typing lesson, the students listened to code being sent by Saunders, and they learned to copy on the “mill”.

Other typing students were trained to transcribe the paper tapes being used to run the code machines. They intently watched a character of the tape be revealed and typed the corresponding letter. Many students were particular fond of this activity, and expressed disappointment that the fun ended when the bell rang.

Students were also trained to copy by flashing light. After they had mastered copying code by sound, they were instructed to watch a flashing light which flashed along with the aural code. Then, the sound was turned off, and they continued to copy by sight.

Sending practice was also given, with sending stations being set up on old laboratory tables. These were wired up so that students could listen to perfect code from the machine and then listen as they tried to duplicate the sounds with their own fists.

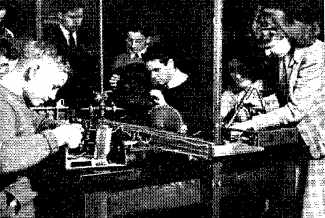

Interested students, both boys and girls, also took part in classes in radio theory, largely following ARRL study materials. By rounding up defunct receivers, they were able to scrounge components to build projects such as code oscillators, as the students here demonstrate.

Interested students, both boys and girls, also took part in classes in radio theory, largely following ARRL study materials. By rounding up defunct receivers, they were able to scrounge components to build projects such as code oscillators, as the students here demonstrate.

Saunders reported that it had been a lot of work getting the school geared up to study radio, but he and the students were very enthused about it. He reported that the many extra hours spent at school working on it were a suitable substitute for ham radio’s being off the air for the duration. In fact, his wife reported that “it is even worse now than before the war” since he was at least at home–albeit in his shack–in the prewar years.