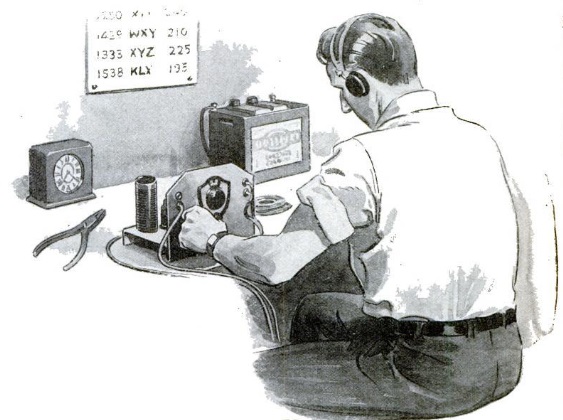

This gentleman, shown 85 years ago this month in the September 1937 issue of Popular Science, might be listening to a standard broadcast program. But chances are, he’s tuning the longwaves, listening to ships or aircraft beacons on what was then called the X-Band (not to be confused with the modern X band of 7-11.2 GHz, or the expanded AM broadcast band of 1610-1700 kHz).

This gentleman, shown 85 years ago this month in the September 1937 issue of Popular Science, might be listening to a standard broadcast program. But chances are, he’s tuning the longwaves, listening to ships or aircraft beacons on what was then called the X-Band (not to be confused with the modern X band of 7-11.2 GHz, or the expanded AM broadcast band of 1610-1700 kHz).

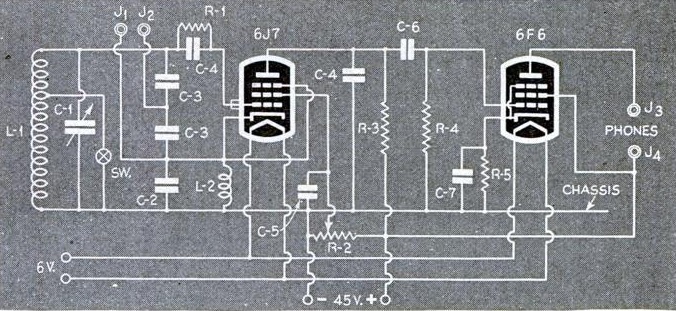

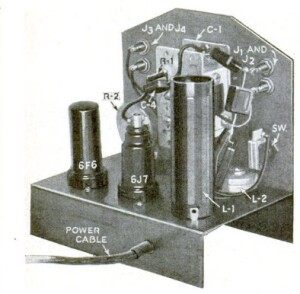

The set used two tubes to cover 250-1650 kHz in two bands, with a tapped coil and a toggle switch to short out part of the coil for the higher frequencies. The circuit could be duplicated today, since there don’t appear to be any unobtainium parts. You wound the coil yourself, although it would take a bit of patience, since it consisted of 360 turns of number 32 wire carefully wound on a 1-1/4″ form.

Government weather reports were easy to tune in with the set, since they were transmitted on the A-N beacon frequencies. If you lived right on an airway, you would hear a continuous carrier. But more likely, you would hear either an A or an N in Morse code, indicating you were off to one side. Once a minute the station would send its call letters. Weather reports were broadcast on a regular basis.

In addition, lighthouse radio beacons consisted of one letter repeated for one minute. These were in clusters of three stations, and they would take turns sending a letter, allowing a ship radio compass to determine its position.

The article warned that, like all regenerative detectors, the set was capable of interfering with nearby receivers if improperly tuned. To avoid this, the article advised tuning in from the edge of the signal, and turning down the regeneration before tuning in the exact carrier frequency.