This self-explanatory image appeared on the cover of Radio News 90 years ago this month, December 1927.

This self-explanatory image appeared on the cover of Radio News 90 years ago this month, December 1927.

This self-explanatory image appeared on the cover of Radio News 90 years ago this month, December 1927.

This self-explanatory image appeared on the cover of Radio News 90 years ago this month, December 1927.

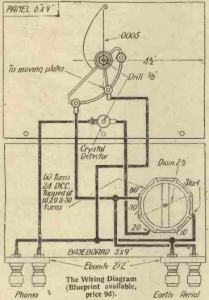

The plans for this British crystal set appeared 90 years ago in the December 17, 1927 issue of Amateur Wireless.

The plans for this British crystal set appeared 90 years ago in the December 17, 1927 issue of Amateur Wireless.

The set was billed as an ideal Christmas gift for someone living close to a BBC station. “A receiver such as this is inexpensive to build and would make an admirable Christmas gift to someone who lives near a B.B.C. station and has facilities for the erection of a reasonably efficient aerial-earth system.”

According to the article, if the set was equipped with a good aerial and earth, it would work two pairs of headphones with good volume, at a range of up to 12 miles from a main BBC station, or about half that distance from a relay station. The set was simple to operate, since it used a “permanent” crystal detector.

According to the article, if the set was equipped with a good aerial and earth, it would work two pairs of headphones with good volume, at a range of up to 12 miles from a main BBC station, or about half that distance from a relay station. The set was simple to operate, since it used a “permanent” crystal detector.

The article used quotation marks, since apparently the detector (available from either R.I. and Varley, or the Jewel Pen Company) was capable of an initial adjustment. “When testing on actual reception, carefully adjust the crystal detector until loudest results are obtained, and then leave well alone, as far as the detector is concerned.”

Shown here in the October 1922 issue of QST is Marion Adaire Garmhausen, who the magazine reports was “born on May 28, 1899, but swears she does not look a day over sixteen.”

Miss Garmhausen was a telegraph operator who went to wireless school just after the war. There, she found an issue of QST that had been left lying about. She was struck by the spirit of the organization and became licensed as 3BCK. She was the author of a number of articles for QST, including “How to Build a Wireless Station” in the July 1920 issue and “Breaking Out” in the May 1921 issue.

She was featured in the September 2002 issue of QST which revealed that she was “The First YL.” That article reproduces a 1920 letter to her addressed to “My Dear YL,” which pointed out that the new phrase was created for her benefit, “as you will readily see that OM will not fit and OL would certainly be most inapplicable.”

In 1947, Santa undoubtedly received many requests for one of these little beauties. It was obviously an idea before its time, but Air King obviously anticipated the cell phone camera. With the available technology of the day, they produced this combination camera-radio, the model A410, shown here in the December 1947 issue of Radio Retailing.

In 1947, Santa undoubtedly received many requests for one of these little beauties. It was obviously an idea before its time, but Air King obviously anticipated the cell phone camera. With the available technology of the day, they produced this combination camera-radio, the model A410, shown here in the December 1947 issue of Radio Retailing.

The camera featured a 50 mm lens, and could take either black and white or color pictures on standard 828 film.

The four tube radio ran on one flashlight battery and a 67-1/2 volt B battery.

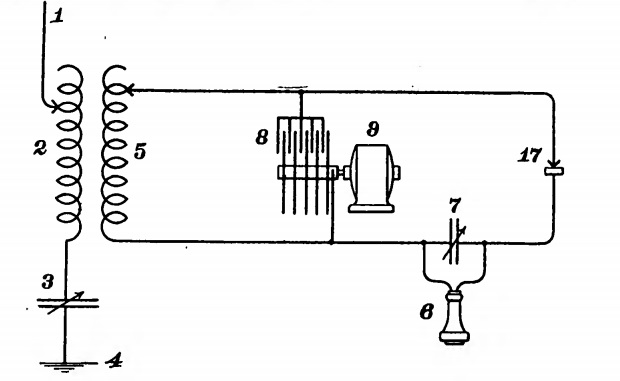

Ninety years ago today, the December 17, 1927, issue of Radio World carried the report of DX Hound Thomas F. Meagher. Meagher described his location in New York City as the one bad disadvantage he was saddled with, due to the proximity of so many local stations. But despite the disadvantageous location, Meagher was able to pull in over the course of six nights a total of 98 different stations in 43 cities. His log included stations as far west as WHO Des Moines and WCCO Minneapolis/St. Paul.

Meagher pulled this off with a loop antenna and the Magnaformer 9-8 receiver, the construction details of which were included in earlier issues of the magazine.

Meagher pointed out that he lived only 3/4 mile from WABC, and also close to other stations. The advantage of the Magnaformer was that it was able to “get in between” the stations with good selectivity. For example, he noted how he was able to go between WOR and WHN and pull in five out-of-town stations, WHJ, CFCF, WCCO, WFI, and WTAM. He reported that he took full advantage of the set’s loop antenna to null out the strong local stations.

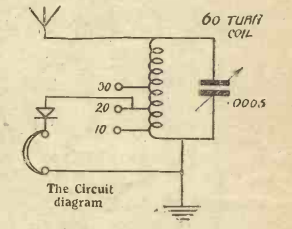

Meagher’s home at 7765 75th Street, Glendale, New York, is shown in the article. And lo and

Meagher’s home at 7765 75th Street, Glendale, New York, is shown in the article. And lo and

behold, the same house is still recognizable in the Google Street View shown below.

Seventy years ago, Santa was getting ready to head down the chimney with some of these Philco radios and phonographs shown in this ad from the December 15, 1947, issue of Life magazine.

Seventy years ago, Santa was getting ready to head down the chimney with some of these Philco radios and phonographs shown in this ad from the December 15, 1947, issue of Life magazine.

The featured console was the Philco 1270, with a list price of $359.70. It featured an FM tuner, and also promised to let you say goodbye to record noise, with the “Philco Electronic Scratch Eliminator, the device that separates noise from music for the first time in the history of record-playing.”

If you wanted to add some scratches to those records to test the capabilities, the ad also featured two phonographs that could probably do the trick, models 1200 and 1201. The record was inserted into a slot on the front, and the ad promised “no more fussing with lids, tone-arms, or controls.” Model 1200 was just a record player, while model 1201 also featured a radio. Both were portable and could be carried anywhere.

You can see the 1270 in action at the following video. While not mentioned in the ad, you can see from the video that the set also tuned 6-15.5 MHz shortwave.

Ninety years ago, the Fahnestock clip was well established in the free world as a convenient method of making electrical connections. They were readily available wherever radio and electrical supplies were sold.

Ninety years ago, the Fahnestock clip was well established in the free world as a convenient method of making electrical connections. They were readily available wherever radio and electrical supplies were sold.

Soviet amateurs, on the other hand, were forced to use a bit more ingenuity, as shown from this issue, 1927 issue number 6 of Радио любитель (Radio Amateur) magazine. The article, by Engineer V.D. Romanov, shows how to make Fahnestock clips! While I can’t read the text, the diagrams are quite clear. The clips can be cut from sheet metal. Or for the truly enterprising Soviet ham, the article shows how to fabricate makeshift Fahnestock clips from wire!

There will undoubtedly come a day when the Fahnestock clip becomes unobtainium. When that happens, you’ll be able to make your own. In the meantime, you can get them at Amazon:

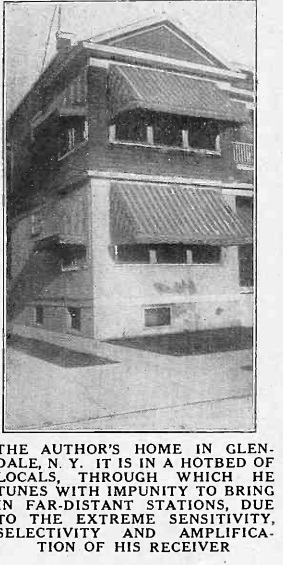

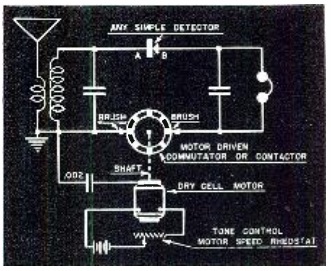

A hundred years ago this month, the December 1917 issue of Wireless Age showed this method of received undamped waves (CW) with a crystal detector. Unlike spark signals, the CW signals had no audio modulation. Therefore, with just a crystal set, you can’t hear anything.

A hundred years ago this month, the December 1917 issue of Wireless Age showed this method of received undamped waves (CW) with a crystal detector. Unlike spark signals, the CW signals had no audio modulation. Therefore, with just a crystal set, you can’t hear anything.

The conventional method to receive CW signals is with a receiver that has a BFO, an oscillator that mixes with the incoming signal. When the CW signal is transmitted, you hear a tone which is the difference between the frequencies of the two signals.

This circuit uses a rotating variable condenser in the circuit. The article includes alternate placements, but the idea is the same. An audio frequency (the same as the frequency of the motor’s rotation) is imposed on the signal, and the code can be copied in the headphone. The pitch you hear is equal to the frequency at which the capacitor is rotating.

We previously showed a similar idea from 1943 in this post. In this circuit, CW can be copies by interrupting the circuit with a motor driving a commutator.

We previously showed a similar idea from 1943 in this post. In this circuit, CW can be copies by interrupting the circuit with a motor driving a commutator.

Eighty years ago, the December 1937 issue of Popular Mechanics carried the plans for this simple two-tube portable broadcast set. It featured two type 30 tubes, one serving as regenerative detector and the other as audio amplifier to drive a set of headphones. The set could be taken on hikes or bike rides or to the ball game. And since the set ran a long time on a set of batteries, it was said to have a definite value in flood, hurricane, or earthquake areas.

Eighty years ago, the December 1937 issue of Popular Mechanics carried the plans for this simple two-tube portable broadcast set. It featured two type 30 tubes, one serving as regenerative detector and the other as audio amplifier to drive a set of headphones. The set could be taken on hikes or bike rides or to the ball game. And since the set ran a long time on a set of batteries, it was said to have a definite value in flood, hurricane, or earthquake areas.

The 22.5 volt B battery would last about six months. The filaments were powered by two flashlight batteries, which would be good for about five hours at a cost of only a dime each.

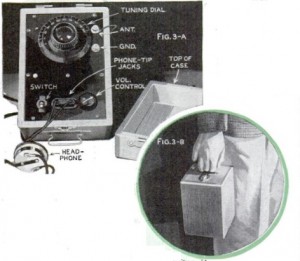

Sixty years ago this month, the December 1957 issue of Boys’ Life announced the 1958 running of the magazine’s radio contest for hams and SWL’s.

Sixty years ago this month, the December 1957 issue of Boys’ Life announced the 1958 running of the magazine’s radio contest for hams and SWL’s.

According to the magazine, over 300 Scouts and Explorers at the 1957 Jamboree had been licensed hams, and most of them got their start with one of the BL radio contests.

The 1958 running had two classes for SWL’s. Class A entries used manufactured receivers or converted surplus sets. Class B was for scouts using homemade receivers they made themselves.

There was also a class for licensed hams, but the magazine noted that licensed hams were never eligible for prizes for winning contests. Hams were to call CQ BSA, and exchanged message number, RST, rank in scouting, and BSA region or country. For the SWL categories, prizes ranged from ARRL memberships to receivers.

This year, the SWL contest was based entirely on the number of US and Canadian regions logged, number of states, and number of countries. Once a station in a particular region, state, or country was logged, there was no reason to log another. There were bonus points for logging all regions and all states, and any station qualified, whether it was broadcast, TV, FM, code, armed forces, police, amateur, or other.

The log had to include a 25 word written statement of either “I like short-wave radio because…” or “I’d like to get an amateur radio operator’s license because….”

Logs were to be signed by an adult certifying that the scout logged the stations by himself, alone.