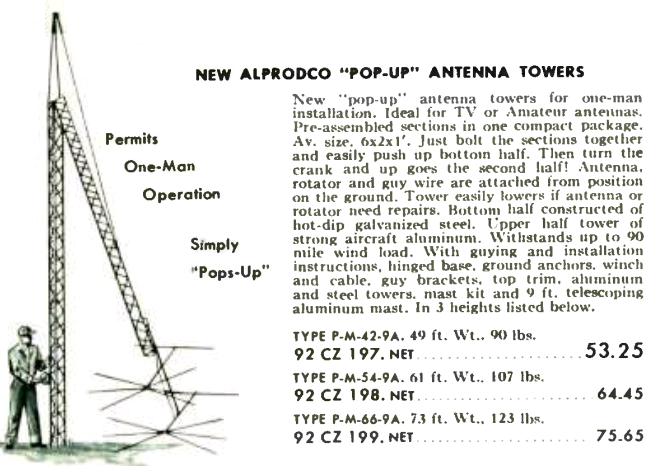

This is either a great idea, or a really bad idea. Whichever it was, it appeared in the 1956 Allied Radio catalog. The idea was simplicity itself, as revealed by the diagram. One man can put up an antenna and a 73 foot tower without ever leaving the ground. “Just bolt the sections together and easily push up bottom half. Then turn the crank and up goes the second half!” The bottom half was steel, and the top half was aluminum. What could possibly go wrong?

Sixty years later, these don’t seem to be available, and even though I’m not a mechanical engineer, I think I can see a couple of reasons why. First of all, I bet the top section needs a little nudge from a second man on the ground to start cranking from that insanely acute angle, but that’s not an insurmountable problem. I would definitely want to be wearing a hardhat when the top section travels the last couple of inches, since it seems to me that it’s going to drop into place by gravity without any control from the crank. And during the time that the top half is sticking out perpendicular, I would think that it really needs to be firmly tied down on the other side, to keep the whole thing from tipping over.

The biggest problem I see is that the cable is a permanent structural part of the tower. If the cable breaks, or even if some curious passerby wonders what happens when the crank is turned, nothing is holding up the tower other than gravity and the guy wires.

The description says that it will withstand 90 MPH winds. But I wouldn’t want to be standing anywhere near it when those winds were blowing.

Of course, maybe I’m wrong about those things. If so, then this is a great idea.

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

![]()