Today marks the 75th anniversary of the death of a British Boy Scout, Derrick Belfall, who gave his life in the service of his country and his King.

Just over 75 years ago, the November 18, 1940, issue of Life magazine carried this photo of British air raid wardens gathering prior to having to go to work for the night. The man on the phone is just receiving the “yellow warning” advising that enemy planes were approaching the country. The young man resting is probably a messenger, who would be called upon to deliver messages to civilian defense headquarters if the telephones failed.

Just over 75 years ago, the November 18, 1940, issue of Life magazine carried this photo of British air raid wardens gathering prior to having to go to work for the night. The man on the phone is just receiving the “yellow warning” advising that enemy planes were approaching the country. The young man resting is probably a messenger, who would be called upon to deliver messages to civilian defense headquarters if the telephones failed.

The men here are in Churchill, a village coincidentally sharing the name of the prime minister, located about 14 miles from the port of Bristol. These men so far felt a little out of the war, since, there had been nothing to do, no bomb wreckage, no casualties, no fires. But the same scene was playing itself out in other cities and villages, and many of those men, young and old, would soon be at the heart of the war.

On the night of December 2, 1940, a similar scene was playing itself out just a few miles away in Bristol. Planes were approaching the country, and the men of Bristol received the warning. Among them was a fourteen year old Boy Scout, Derrick Belfall, of 109 Bishop Rd, Bishopston, Bristol, the only son of Cecil Ernest and Mary (née Miller) Belfall. Like the young man in the photo above, he was a civilian defense messenger.

Under the regulations, the minimum age for messengers was sixteen. But fourteen-year-old Belfall had been persistent, and his parents and the authorities had finally allowed him to serve. On December 2, the yellow warning turned into a real attack on Bristol, and the civilian defense volunteers had a long difficult evening ahead of them.

Another Boy Scout messenger explained, in the September 1942 issue of Boys’ Life, the duties of messenger:

When a bomb drops one of the first people on the spot is either the head warden or one of the senior wardens. He always has a messenger with him; one of us Scouts. What he does as soon as he gets there is to make out a report on what has happened, give it to that messenger and the messenger rides down to the post, which we call the pill box.

Inside the pill box there is a telephone. That is the only telephone we are allowed to use during an air raid. But sometimes the telephone lines get broken when a bomb hits the road. Then instead of just having to ride to the post and telephoning, we messengers have got to ride down to the control center. Sometimes it is a long way and sometimes it isn’t. In my case it is three miles; that’s three miles there and three miles back, maybe ten times in one night. Not only do we send one messenger but three minutes after the first messenger is gone we always send another one so if the first one gets bumped off the second one may get through.

The most complete account of Derrick Belfall’s actions that night appeared in the Chelmsford Chronicle, January 17, 1941:

In the six hour long air raid on Bristol early in December last Derrick Belfall took a message regardless of his own safety right through the worst danger area of the city with bombs dropping all around him. He got through with his message and he got back, his hands torn and bleeding. When told to go and rest, he said “No thanks”; please let me have a stirrup pump, I want to put out a fire that I passed down the road.

They told Derrick he was too exhausted to go out again, but the lad took a pump, slipped quietly out and succeeded by himself in getting the fire under control. A little later he rescued a baby from a blazing house.

He reported back at his post and found that telephonic communications had broken down, An urgent message had to be got through. Without a moment’s hesitation Derrick volunteered to take it. Out he went with enemy raiders overhead dropping bombs all along the route. He reached the Central Police Headquarters.

And then a bomb struck him down.

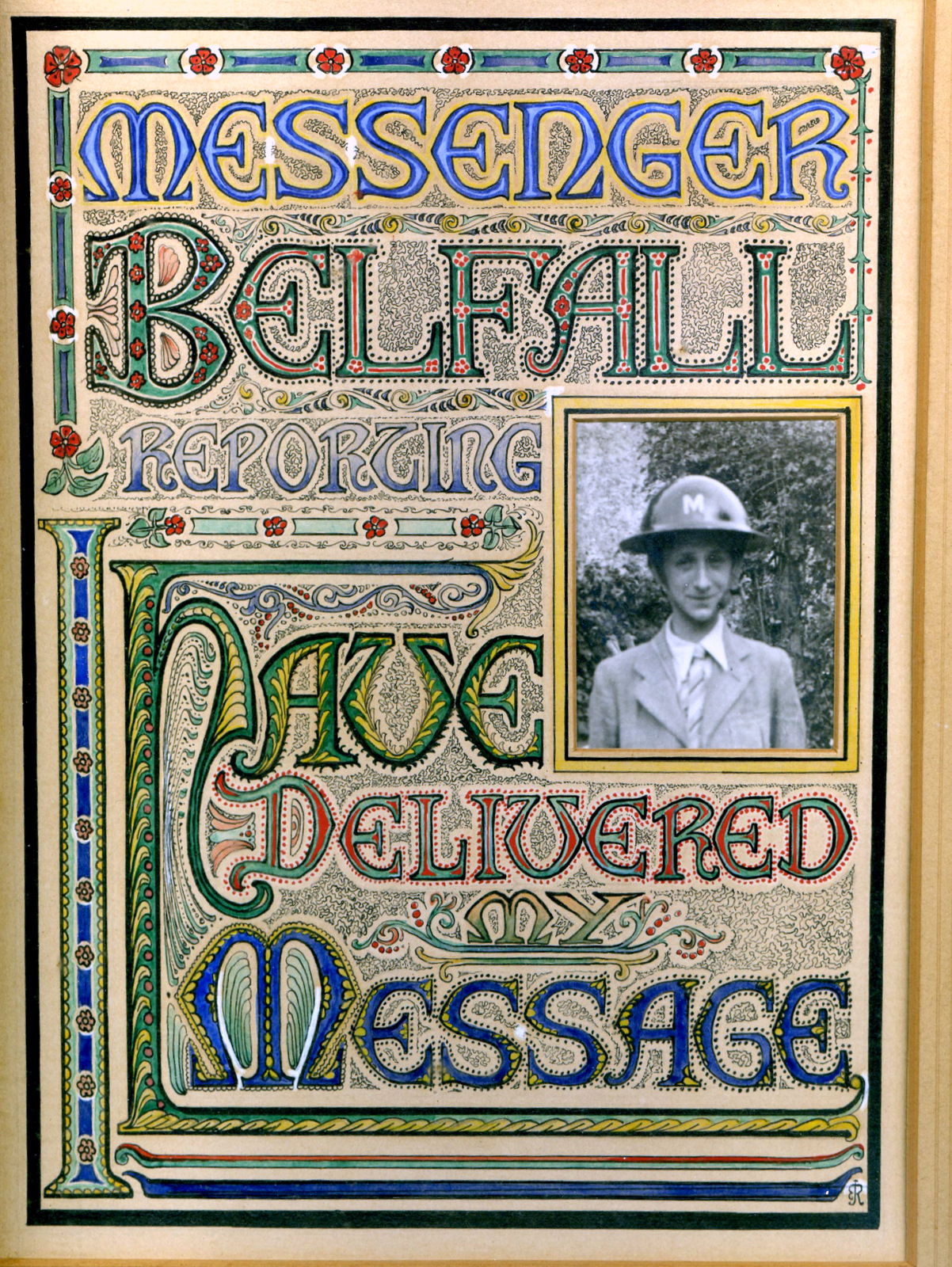

He was rushed to hospital dying “Messenger Belfall reporting – I’ve delivered my message,” he murmured. That was his last breath. Derrick Cecil Belfall died on active service aged 14 years 11 months.

After recounting Scout Belfall’s story and those of other scouts responsible for acts of bravery, the American Chief Scout Executive, James E. West, had this to say:

Of course, all of us hope that none of our Scouts will ever be called upon to face this type of emergency here in America, but it is my conviction that they are qualified to meet any situation in the same spirit. Bear in mind that these boys are typical of Scouts in your own community, yes, in your own Troop. That they probably had training no better than what you yourselves and your brother Scouts secured under your own Scoutmaster and other Troop leaders. They were not specialists but were equipped with only such knowledge as is normally given to Scouts through our Advancement Program. Yet how nobly these Scouts and Scout Leaders lived up to our Scout Motto “Be Prepared.”

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank Mrs. Rita McInnes, a neighbor of the Belfall family, for providing the photograph of Derrick Belfall, and also for providing the newspaper article quoted above. The illuminated photograph containing Derrick’s last words hung for many years in the Belfall home, and I am grateful to Mrs. McInnes for preserving it and allowing me to share it.

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

![]()