One of three common rooms at the Livermore shelter. Doors lead to individual family rooms.

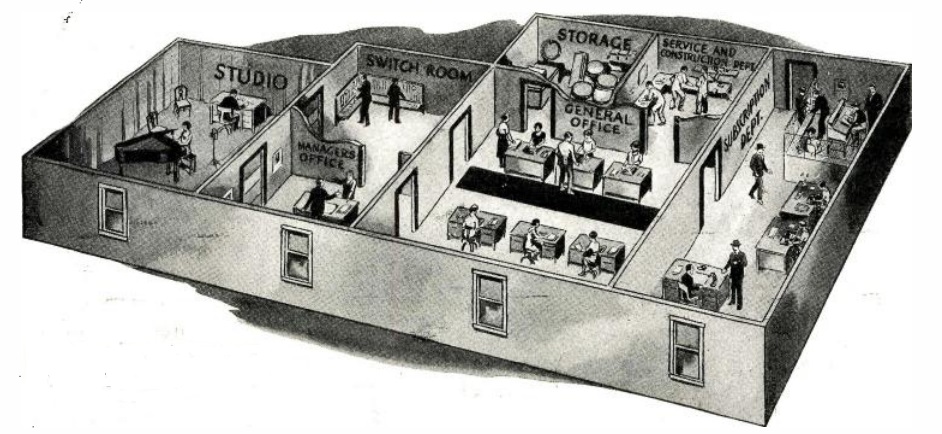

On April 19-23, 1965, a symposium was held in Washington on “Protective Structures for Civilian Populations.” The proceedings of that symposium were published, and contain reports of a number of interesting fallout shelter concepts. Some were mere concepts, but one that had been implemented was a cooperative group shelter near Livermore, California.

The author of that report was Arthur J. Hudgins, who is identified as being with the Livermore Radiation Laboratory. He noted that both he and his associates had concluded that it would be economically practical to build a shelter sufficient for any attack, as long as it did not involve a large nuclear expolosion within three or four miles. But they also concluded that “the post-attack problems to be faced by a single family upon leaving a shelter would be most serious.” After much discussion, they concluded that a shelter group would have a good chance of not only surviving the attack, but also successfully meeting the later problems.

To carry out their plans, they incorporated as Survival Associates, Inc., a California corporation, and set out to build the shelter. By the time land had been procured and building began, 34 families had become members. Initially, obtaining the building permit looked problematic, since “fallout shelter” was not a use mentioned in the county zoning ordinance. But while the application was pending came the Berlin crisis, and the Board of Supervisors quickly came around to the need. The members concluded that the best design would be a corrugated steel arch covered by earth, set on a concrete slab measuring 25 by 142 feet.

Entry to the shelter. A more recent photo of what appears to be the same entry can be found at this site.

The entry doors consisted of surplus steel ship doors, and there was a small room with a generator near each entrance. Near each entry was a shielded observation tower, which would provide a view of the surrounding countryside. Inside, there were 32 rooms for individual families, each measuring 7.5 feet square with an 8 foot ceiling. There were a total of six toilets and three kitchens.

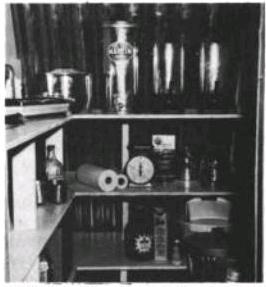

One of the three kitchens.

Each kitchen was supplied by a 3000 gallon undergound tank, and each pair of toilets was served by a 1000 gallon tank. The tanks could also be refilled from the peacetime water system.

Common areas were lit with flourescent fixtures, and each room was equipped with a 100 watt lightbulb, which could be replaced with a 25 watt bulb if needed to extend generator run time in an emergency.

In addition to the main entries, there were multiple emergency exits, which consisted of sections of the steel structure that opened inward. These were covered with sand, which would fall inward if necessary to evacuate. Ventillation was provided by a positive-pressure system which pumped in outside air near the entries. During tests, the ventillation system proved more than adequate. In fact, when the ventillation system was shut off and the shelter sealed, most occupants did not notice.

The minimum earth cover over the shelter was four feet, which was calculated to provide a protection factor against fallout of more than 10,000. It was estimated that the structure would withstand a blast of up to 30 PSI. The corporation stocked the shelter with a three-week supply of food to supply 2000 calories per day per person. This consisted mostly of bulgar wheet, sugar, dried milk, vegetable oil, and viatimin tablets. In addition, there was dried fruit, coffee, tea, pancake flour, dry soup mix, peanut butter, and vitamin tablets. Most members also had food stored in their individual rooms, and it was estimated that the group would have an adequate diet for about six weeks.

In addition to other supplies, the shelter was stocked with about 1100 gallons of gasoline, which was calculated to be enough to run the generators for six weeks.

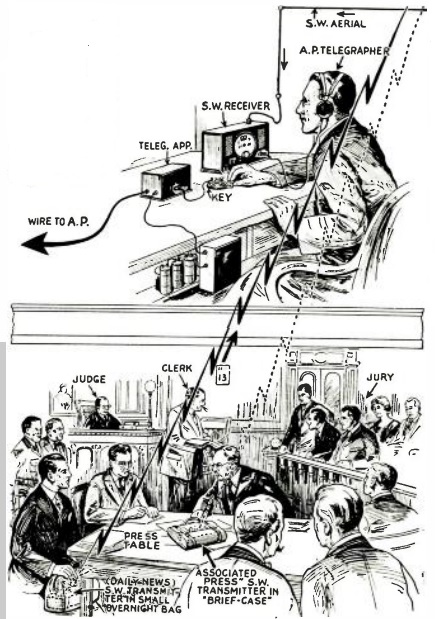

The shelter was equipped with a shortwave receiver, and there were “definite plans” to include an amateur radio transmitter.

At the time of the report, there were a couple of vacancies available, and there was also provision to build a second interconnected shelter at the same site if there was sufficient interest.

The corporation conducted some tests of occupancy. One of those was featured in a 1963 newspaper article. In addition, members had access to the facility at all times with combination locks. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, a number of members stayed at the facility as a precaution.

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

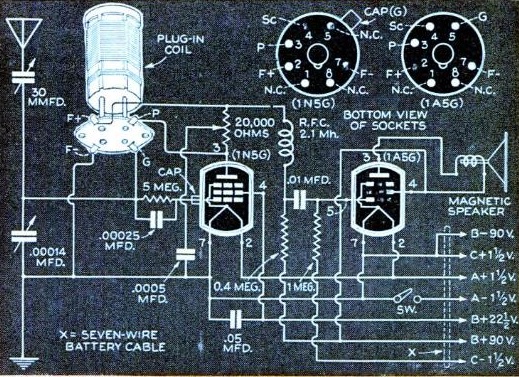

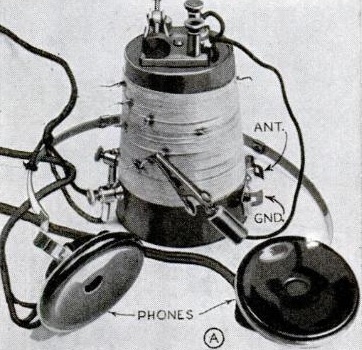

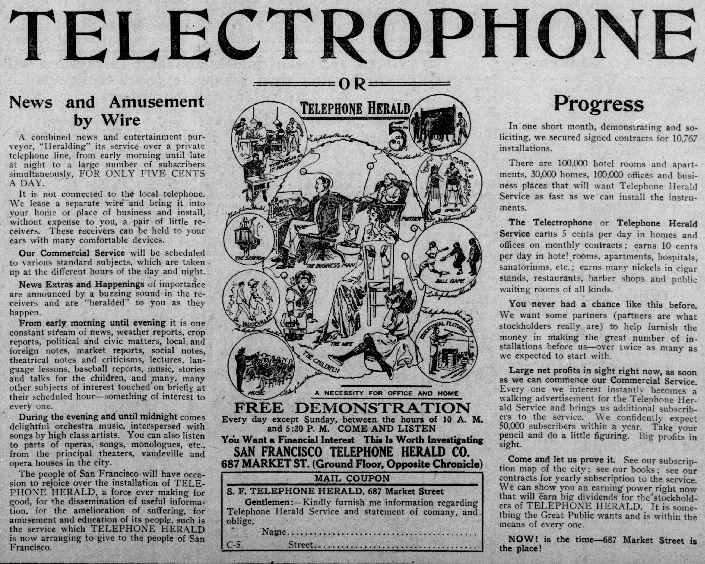

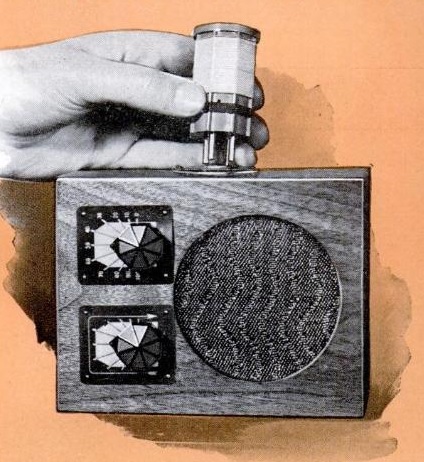

This cute little two-tube broadcast/short wave receiver appeared in Popular Science 75 years ago this month in the June 1940 issue.

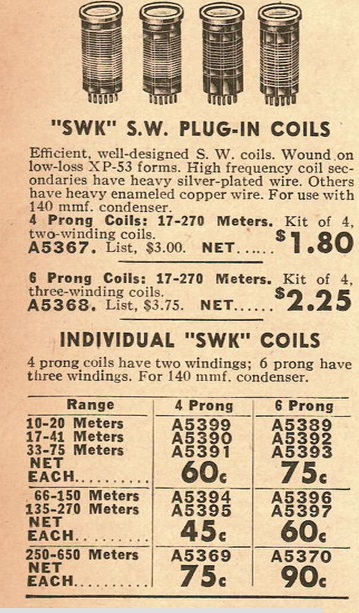

This cute little two-tube broadcast/short wave receiver appeared in Popular Science 75 years ago this month in the June 1940 issue. It used ready-made coils which plugged into the top of the set to change bands. Back in the day, you could buy the coils pre-wound, such as the ones shown here in the 1940 Allied catalog. A set of four coils covering 17-270 meters would cost $1.80. If you wanted to get the bottom of the broadcast band, the coil covering 250-650 meters would be an additional 75 cents. Plug-in coils are unobtanium these days, but AA8V has a good description of how to make your own forms from a defunct tube and section of PVC.

It used ready-made coils which plugged into the top of the set to change bands. Back in the day, you could buy the coils pre-wound, such as the ones shown here in the 1940 Allied catalog. A set of four coils covering 17-270 meters would cost $1.80. If you wanted to get the bottom of the broadcast band, the coil covering 250-650 meters would be an additional 75 cents. Plug-in coils are unobtanium these days, but AA8V has a good description of how to make your own forms from a defunct tube and section of PVC.![]()