In part 3 of this series, we looked at some of the remarkable distances covered by the Japanese Fu-Go fire balloons of World War II. Some of these balloons were found far inland in North America, including balloons found in Iowa, South Dakota, Manitoba, and Michigan. There’s no record of any of these balloons making it to Minnesota (although there’s the possibility that somewhere in Minnesota lies the rusting wreckage of one). But one of them played an interesting role in Minnesota postwar aviation.

As we covered in part 3, one of the balloons landed near Grand Rapids, Michigan. It was largely intact, and quickly whisked away by the FBI. It ultimately found its way to Lakehurst Naval Air Station in New Jersey, where it remained until the end of the war. In 1946, a young sailor named Don Piccard was stationed there, and was tasked with taking the craft to the dump. (The balloon was labeled as having come from Flint, Michigan, but it’s believed that it was actually the Grand Rapids balloon.)

Lakehurst is famous for lighter-than-air flying, and Piccard was undoubtedly stationed there for a reason. His family had long been active in ligher-than-air flight. His father was Swiss-born Jean Felix Piccard, then a professor of aeronautical engineering at the University of Minnesota. His mother was Jeanette Piccard. Jean Felix and Jeanette in 1933 had piloted a balloon 57,579 feet into the stratosphere. This constituted the world record altitude for flight by a woman, a record held for 29 years until Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in space. If Wikipedia is to believed, Gene Roddenberry named the character Jean-Luc Picard after Jean Felix Piccard or his brother Auguste, another aviation pioneer. In fact, Jean-Luc is supposed to be a descendant of one of the men.

(Jeanette also became, in 1974, the first woman ordained as an Episcopal priest. At the age of 11, in response to the question of what she wanted to be when she grew up, she answered “a priest.” Her mother reportedly ran out of the room in tears. But after her long career in aviation, at the age of 79, she was ordained as one of the “Philadelphia Eleven.”)

Rather than taking the balloon to the dump as directed, the younger Piccard obtained a property pass to keep possession of the war trophy. Upon his discharge, he became a student at the University of Minnesota where his father taught. And he set out figuring out how to fly the balloon.

The Civil Aviation Agency had, at that time, the category of free balloon pilot, but no such license had been issued. A license for an airship pilot carried privileges for free balloons, and Piccard had accomplished most of his flight requirements in balloons with airship pilots. But he had not yet soloed, and he saw the war souvenir as an opportunity to do just that.

While the balloon was apparently in relatively good condition, it did have tears and was in need of repair. A glue adequate to do the job had to be procured. In addition, he needed funds to purchase the hydrogen, as well as kiln-dried sand to serve as ballast. (Sand with moisture would freeze, making for a lethal projectile when dropped.)

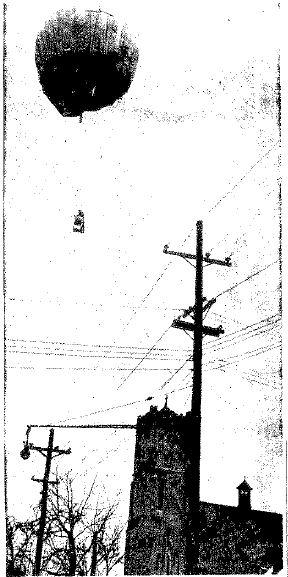

Piccard preparing for the 1947 flight. Image courtesy of Michigan Aviation Archaelogy.

To get the necessary funding, he sought the sponsorship of the Minneapolis Daily Times, which was granted, and the craft bore the paper’s name, above its N number, NX79598. Piccard was also a member of the Army Air Corps ROTC, which became the U.S. Air Force days before the flight. It was also sponsored by the ROTC, and Piccard wore a hastily assembled U.S. Air Force uniform during the flight. He later recounted that not only was his the first U.S. Air Force flight to take place in Minnesota, but also that his was quite possibly the first U.S. Air Force uniform ever worn.

The flight took place on February 16, 1947, from Minneapolis to White Bear Lake. After launch, apparently from South Minneapolis, Piccard had to maintain his altitude by venting the balloon and dropping ballast. He had originally intended to climb to the calculated maximum altitude of 12,000 feet and then begin his descent. But an overcast required him to control the altitude throughout the flight. The winds carried him to White Bear Lake, during which time Piccard had remained aloft for more than the two hours necessary to qualify for his solo flight, and he the CAA subsequently issued him the first ever free balloon pilot license. (This was the balloon’s last flight. Since Piccard didn’t have a bill of sale for the Japanese balloon, he was unable to register the craft.)

The flight received media attention nationwide, and also caused quite a commotion as it landed in White Bear Lake. Apparently, nobody had told the White Bear Lake Police Department that the flight was headed their way, and they were unprepared for the resulting commotion as hundreds of curiosity seekers flooded the area, trespassing on private property. At one point, the officers threatened to arrest the army personnel in the chase vehicle, who they determined must be responsible for the breach of the peace.

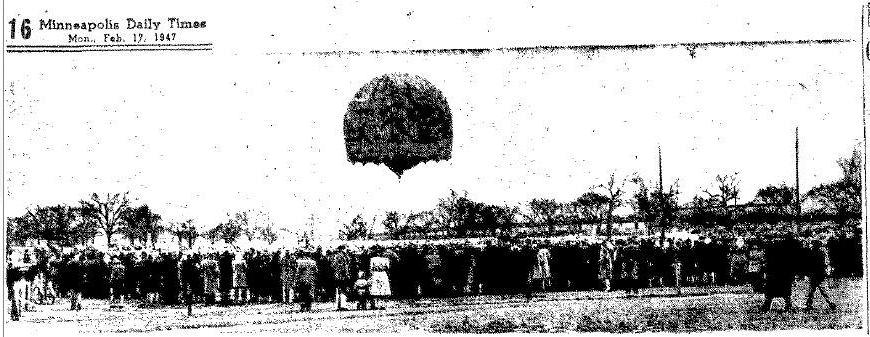

Scene of the landing in White Bear Lake. Image courtesy of Michigan Aviation Archaeology.

The last flight of a Fu-Go balloon. Image courtesy of Michigan Aviation Archaeology.

Since the Daily Times was actually an afternoon newspaper, the morning papers all managed to scoop the sponsor of the flight, although they didn’t refer to it in print as being the Daily Times Flight. Piccard later wrote a detailed account of his flight for Air & Space Smithsonian.

Don Piccard. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Piccard is regarded as the driving force behind the sport of ballooning, and is still active with his company, Piccard Balloons. When I looked at Piccard’s personal web page, www.N6US.com, I mistakenly assumed that he was a ham. While the URL looks like an Amateur Radio call sign, it should be remembered that aircraft tail numbers (or whatever they’re called on balloons) also use the same international prefixes as radio call signs. In this case, N6US is not a radio call sign issued by the FCC, but an aircraft registered to Mr. Piccard.

In 2008, Piccard was inducted into the Minnesota Aviation Hall of Fame. (The other member of the Minnesota Aviation Hall of Fame who has been mentioned in this blog was Sherman Booen, about whom we wrote in connection with the 1940 Armistice Day Blizzard.)

The balloon after launch. Image courtesy of Michigan Aviation Archaeology.

Image courtesy of Michigan Aviation Archaeology.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Jeffrey Benya of Michigan Aviation Archaelogy for giving permission to use the images of the newspaper clippings shown here.

References

- One Balloon Bomber, Slightly Used, by Don Piccard, Smithsonian Air & Space, May 2001.

- The Japanese Attack on Michigan

- Rochester Magazine Interview With Don Piccard

- Balloon Life, December 1999.

- Piccard collection at Univ. of Minn. Libraries.

Read More at Amazon

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon ![]()