Quick Links

For about the past century, the planet Earth has been sending out into the cosmos radio signals, and it’s not uncommon to wonder whether anyone has heard them. The subject sometimes comes up in science fiction. For example, in the 1997 movie Contact, the first message received from an extraterrestrial source was, of all things, a speech by Hitler (conveniently complete with both audio and video). It was reasoned in the movie that this was one of the first television broadcasts from Earth, and as soon as the TV DX’ers in some other part of the galaxy received it, they sent it back. Presumably, I Love Lucy and other programs would follow within a couple of decades.

For the reasons explained below, this is relatively implausible. While it would be a relatively easy matter for another civilization to detect the presence of our signals, actually demodulating them (not to mention sending them back) would be considerably trickier. But it’s not totally impossible.

But there’s another related question lurking here, and that is how difficult it would be for me to receive radio signals from Earth if I decided to visit the moon or some other place in space. Obviously, radio communications is possible at very great distances, since NASA does this on a daily basis. The question is what those of us with more modest equipment would be able to do.

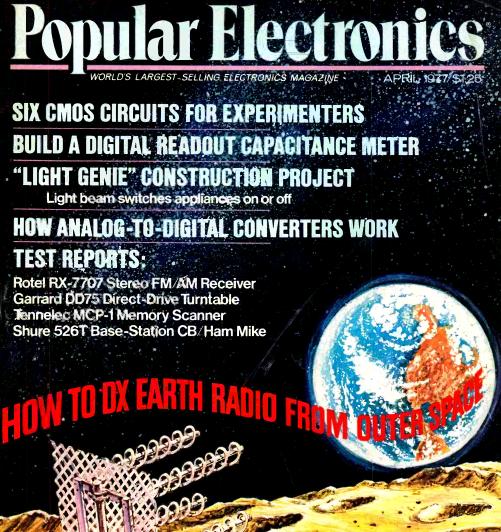

The question is answered by an April 1977 Popular Electronics article written by Glenn Hauser.

Hauser’s focus in this article is primarily on the moon, and he convincingly shows that reception of FM and TV signals would be relatively easy to accomplish with reasonably good receivers and antennas. When the subject comes up, naysayers frequently point out that very few terrestrial stations use antennas that radiate very much energy “straight up.” It turns out, though, that this is actually the reason why many signals could be heard on the moon. After all, the moon is rarely “straight up.” It can be at many points in the sky, and at some of these points, it’s within the main lobe of broadcast stations on Earth.

Most FM and TV stations use what we think of as “omnidirectional” antennas: In other words, antennas that radiate equally strong signals in a full 360 degrees. But most of these antennas have a certain amount of gain: The effective radiated power of the signal is greater than the transmitter’s output power. This is because the “omnidirectional” pattern of the antenna is not omnidirectional at all. Instead, most of the power is concentrated into a single plane. It’s “omnidirectional” in the sense that it’s headed off toward the horizon in all directions. But it’s directional when you think of it in three dimensions. All of the energy is concentrated toward the horizon. This makes sense for the broadcaster, since all of their listeners are located on an (approximate) plane, bounded by the horizon.

This means that a station’s signal is being beamed toward the moon at two times per day: At local moonrise and local moonset. From the point of view of the listener on the moon, this means all of the stations along the Earth’s approaching and receding limbs, a narrow band circling the Earth. A station located at the North or South Pole would have its antenna pointing at the moon on a constant basis. Every other station on Earth would have its antenna pointed at the moon approximately every twelve hours.

There would still be a slight problem, however, since even on this narrow band, there would be multiple stations on any given frequency. I suspect that on some popular frequencies, this problem would be insurmountable, since the QRM would be just too great.

But there would be some signals that would be quite easy to copy, since they have the frequency to themselves, or share it only with much lower powered stations. Two examples given in the 1977 article is no longer relevant, but they’re good illustrations. Prior to the switch to digital television in the United States, TV channel 68 was occupied by only one station, KVST-TV in Los Angeles, with an ERP of a million watts. And on channel 67, WMPB, the Baltimore PBS channel, was in a similar position. These channels would be relatively easy to monitor from the moon whenever it was moonrise or moonset in Los Angeles or Baltimore. Hauser notes other such examples in Europe and Brazil.

Most of the FM band would be more cacophonous, but there would be some stations operating on relatively clear channels. Due to the FM capture effect, some of these would be relatively easy to hear, even if there was a bit of other activity on the same channel. For example, he cites a number of cases in the educational portion of the FM band (88-92 MHz), where there’s a single high-power station in the United States, with other stations on that channel having much lower power. In those cases, the dominant signal would be easily heard. He also cites a number of high powered Canadian stations operating on channels where only low powered stations existed in the United States. Since the FM situation has been relatively static since 1977, most of these stations would remain fairly easy catches from the moon.

Hauser does point out that longwave and mediumwave (standard AM broadcasts) would be unlikely to penetrate the ionosphere. Only signals above the maximum usable frequency (MUF) could be heard outside the confines of the Earth. Therefore, he notes that it’s unlikely that we had much radio leakage to speak of prior to about the 1930’s, when relatively strong shortwave stations started coming on the air. Since most of these stations operated on regular schedules, it’s likely that they were still radiating, even when the MUF dipped below their transmitter frequency. Those signals would radiate into space. Hauser cites one example of a BBC transmission from the VOA station in Delano, California, being copied by a satellite.

DX’ing by Extraterrestrial Civilizations

The issue raised by the movie Contact is touched on by Hauser, but it’s studied in scholarly detail by a NASA report entitled Eavesdropping Mode and Radio Leakage from Earth by Woodrull T. Sullivan III. While this report doesn’t show a date, it appears to be written post-1978. It answers the question of what extraterrestrial listeners, with equipment comparable to that available on Earth, would be able to hear. It turns out that those extraterrestrial viewers would be able to determine quite a bit, although it’s unlikely that they would be able to demodulate the video of speeches by Hitler.

Even though they might not be able to watch our shows, extraterrestrial monitors within several light years of the Earth would be able to make quite a few reasonable deductions about the Earth, even if they were equipped with only Earth-level receivers and antennas. At least they would have been able to. It turns out that the best source of information would be the video carriers of UHF television stations. With the switch to digital television, some of those extraterrestrials might have concluded that the Earth has gone dark.

But those UHF carriers from a few years ago are still working their way through space, and it’s possible that someone is analyzing them. The article makes clear that the modulation of those signals (the actual audio or video) would be too weak to decode with Earth-level technology. But the presence of the carriers would be apparent. And even with this information, extraterrestrials would be able to come to some intelligent conclusions. They would be able to figure out which star the signals were coming from. And by keeping close track, they would be able to figure out the diameter of the Earth’s orbit around the sun.

They would even be able to figure out the approximate latitudes and longitudes of individual stations. This is because the signals would come and go on a regular schedule as the Earth made its 24-hour rotation. As noted above, stations near the poles would be audible most of the time. As stations got closer and closer to the equator, they would be audible for shorter periods each twelve hours. The Doppler shift of received signals would give further clues as to the latitude of the signals being heard. Eventually, the extraterrestrials would be able to crunch the numbers and figure out the approximate terrestrial locations of the stations. If the correctly assumed that the locations of these signals were close to the locations of greatest human population, they would even be able to roughly map out the population distribution of the Earth.

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon ![]()