American and other allied troops parade through Paris on the occasion of the final Bastille Day of the First World War, July 14, 1918.

Category Archives: World War 1

July 4, 1918

USMC photo, via Wikimedia Commons.

In what would be the final Fourth of July of the War, American Marines parade through Paris a hundred years ago today, July 4, 1918.

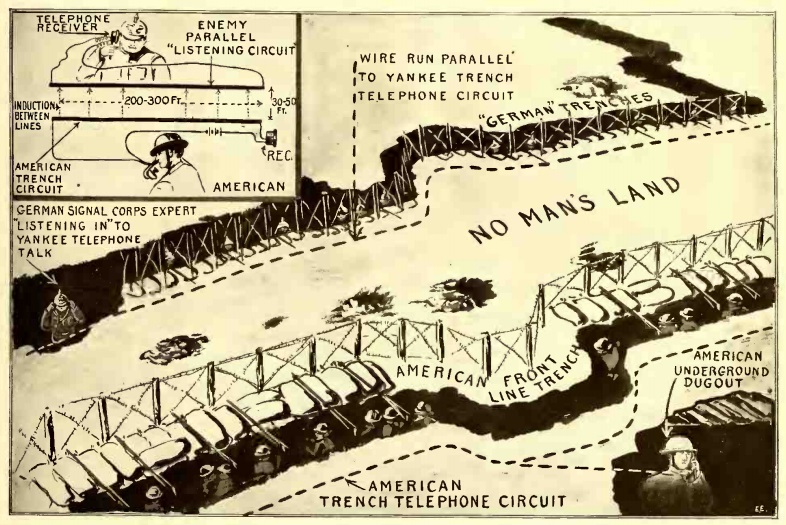

Listening In On Enemy Trenches: 1918

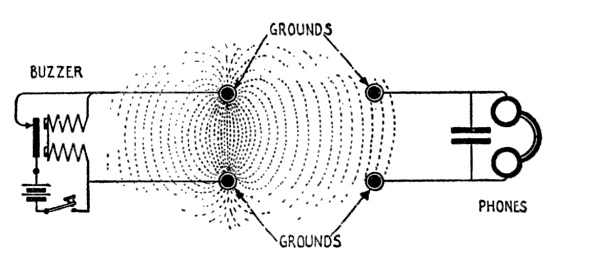

This diagram appeared a hundred years ago this month in the May 1918 issue of Electrical Experimenter, and explains why users of field telephones in the trenches had to maintain security in their communications, even though there was no possibility that the line was tapped.

This diagram appeared a hundred years ago this month in the May 1918 issue of Electrical Experimenter, and explains why users of field telephones in the trenches had to maintain security in their communications, even though there was no possibility that the line was tapped.

The diagram shows the Germans listening in on the Americans’ telephones, but it could just as easily be the other way around. By running a line parallel to the other side’s line, it was possible to pick up the conversation inductively. A powerful amplifier might be used, but in many cases, it was possible to listen in with an ordinary telephone receiver hooked to both ends of the line.

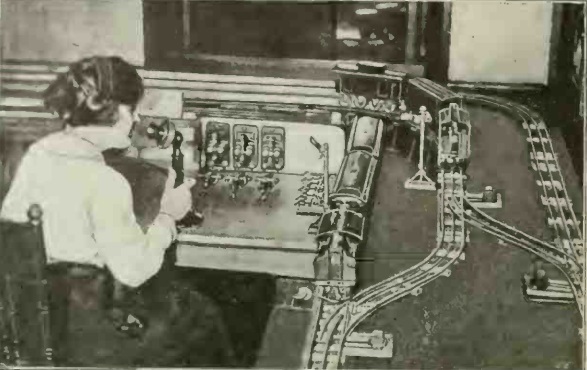

1918 Train Dispatching

A century ago, with much of the labor force off to war, American industry turned to women to fill many jobs traditionally held by their male counterparts. Shown here is one of the hundreds of young women being trained to be train dispatchers. The article, in the April 1918 issue of Electrical Experimenter, pointed out that the job was exacting, and in the real world, mistakes could easily mean death or dismemberment. Therefore, the women were trained on the model railroad shown here, before being unleashed on the real rails. The dispatcher would set signals and switches, with the model trains responding.

A century ago, with much of the labor force off to war, American industry turned to women to fill many jobs traditionally held by their male counterparts. Shown here is one of the hundreds of young women being trained to be train dispatchers. The article, in the April 1918 issue of Electrical Experimenter, pointed out that the job was exacting, and in the real world, mistakes could easily mean death or dismemberment. Therefore, the women were trained on the model railroad shown here, before being unleashed on the real rails. The dispatcher would set signals and switches, with the model trains responding.

1918 Boys’ Life Looks at Wireless

A hundred years ago this month, the March 1918 issue of Boys’ Life magazine included this article by F.A. Collins (probably Archie Frederick Collins) about the state of radio, especially as it related to war. He starts by explaining that “the thing that was impossible yesterday, today is indispensable in commerce and war, wireless telegraphy.”

A hundred years ago this month, the March 1918 issue of Boys’ Life magazine included this article by F.A. Collins (probably Archie Frederick Collins) about the state of radio, especially as it related to war. He starts by explaining that “the thing that was impossible yesterday, today is indispensable in commerce and war, wireless telegraphy.”

And he makes clear that the radio section of the Signal Corps was something especially within the grasp of scouts:

Probably no country in the world can recruit men for this exciting service in such numbers as the United States. There are already tens of thousands of boys throughout the country who have had valuable training as amateurs. It has been estimated that this army of amateurs exceeded over 100,000 boys and girls. Thousands of Boy Scouts, for example, have an excellent working knowledge of wireless and have learned to transmit at a rate of twenty words a minute or faster. The Government does not accept operators under eighteen years of age and many of these boys are practical wireless operators by the time they reach this age ready to enlist in this interesting branch of service.

Women’s Machine Gun Squad Police Reserves, 1918

If the Kaiser had met these women, he would have realized that he didn’t have a chance. And any miscreants in New York would have known that policing the city wouldn’t suffer when the men were overseas at war. Shown here are three members of the Women’s Machine Gun Squad Police Reserves, New York City.

In this International Film Service photograph dated August 1918, Capt. Elise Reniger is shown at the ready with the machine gun, reported to have a killing range of two miles and be able to fire 500 shots per minute. Miss Helen M. Striffler is in the rear seat, and Mrs. Ivan Farasoff is driving the Harley-Davidson.

This and other photos of the role of women on the home front of World War I can be found at the National Archives.

Sinking of the Tuscania, 1918

SS Tuscania. Wikipedia Image.

Today marks the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the SS Tuscania, February 5, 1918. The ship was a luxury liner of the Cunard Line, and was serving as a troop transport, carrying American troops to Europe. The ship left Hoboken with 384 crew and 2013 army personnel aboard. On the morning of February 5, a German submarine sighted the convoy and stalked it until darkness. At 6:40 p.m., it fired two torpedoes, one of which sent the ship to the bottom of the Irish Sea. 210 men were killed in the attack.

Harry Truman. Wikipedia image.

One of the notable survivors was 20-year-old soldier Harry R. Truman (not to be confused with the President), notable for becoming a victim of Mt. St. Helens in 1980.

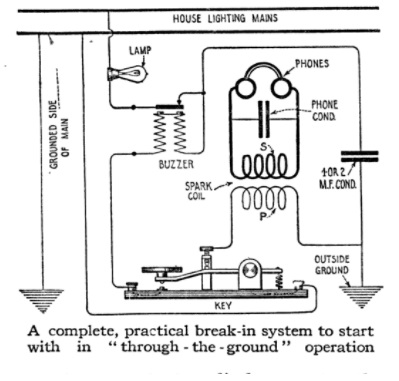

1918 Ground Current Telegraph

With civilian radio (both transmitting and receiving) shut down for the duration of the war, hams a hundred years ago still had a desire to engage in communications. As we’ve seen prevsiously (here, here, here and here), one method of communicating without the use of radio waves is a ground-conduction telegraph. And a hundred years ago this month, the January 1918 issue of Popular Science showed how to do it.

With civilian radio (both transmitting and receiving) shut down for the duration of the war, hams a hundred years ago still had a desire to engage in communications. As we’ve seen prevsiously (here, here, here and here), one method of communicating without the use of radio waves is a ground-conduction telegraph. And a hundred years ago this month, the January 1918 issue of Popular Science showed how to do it.

The magazine noted that “because the Government, for good and sufficient reasons, has put a ban on amateur wireless stations, it does not follow that all your activities must stop.” It noted that communicating by ground wireless was “almost as interesting” as actual radio and was “permitted by the Government, since high tension apparatus need not be used, at least not in their normal capacities.”

While the magazine noted that the Allies were apparently not using this type of communication, “for all we know the Germans may be using it now,” and that it had a potential range of forty miles, and perhaps more through salt water. (The 40 mile estimate seems extremely optimistic, but I can’t say I’ve ever tried it.)

In addition to the basic circuit shown above, the magazine also showed this more advanced setup, which permitted full break-in operation (with the addition of a normally-closed contact to the key). It looks just slightly dangerous, and would probably trip a modern ground fault interrupter. It doesn’t appear to send any signal over the power lines, but does use the electric service ground as one of the two connections.

In addition to the basic circuit shown above, the magazine also showed this more advanced setup, which permitted full break-in operation (with the addition of a normally-closed contact to the key). It looks just slightly dangerous, and would probably trip a modern ground fault interrupter. It doesn’t appear to send any signal over the power lines, but does use the electric service ground as one of the two connections.

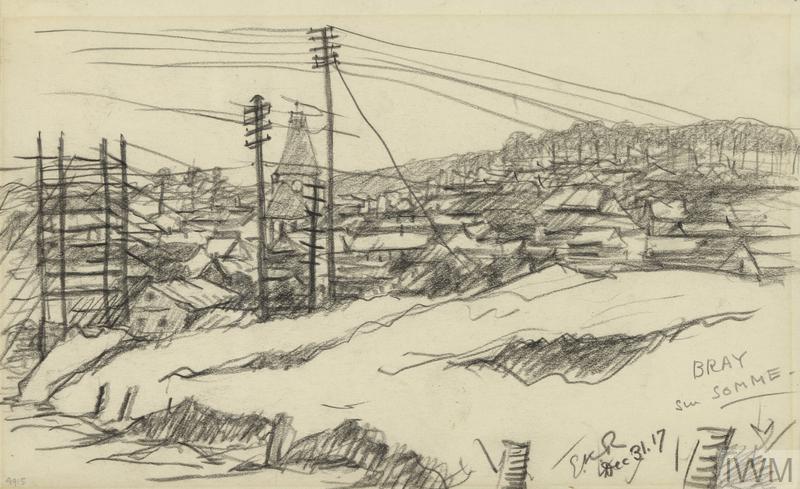

Dec. 31, 1917, Bray-sur-Somme, France

Imperial War Museum image. Bray-sur-Somme, December 31 1917 (Art.IWM ART 4915) Copyright: © IWM.

This sketch was made a hundred years ago today, December 31, 1917, by British officer Major Geoffrey K Rose. It shows the French town of Bray-sur-Somme.

Major Rose (1889-1959) served on the Western Front for three years, and made over 150 sketches during that time. Bray-sur-Somme was initially occupied by the Germans in August 1914, but was evacuated in October of that year, with the front being north of town. For the next 26 months, including when this sketch was made, the town served as a center for rest and recuperation for the French Army, and later the British.

It is thus likely that Maj. Rose was on leave when he made this sketch. In March 1918 the town was, however, taken again by the Germans, and it remained in their hands until the town suffered heavy damage when the British re-took it in August 1918.

L’église Saint-Nicolas, Wikipedia photo.

Recognizable in the sketch is the distinctive tower of the Church of Saint-Nicolas, shown here in a modern photo.

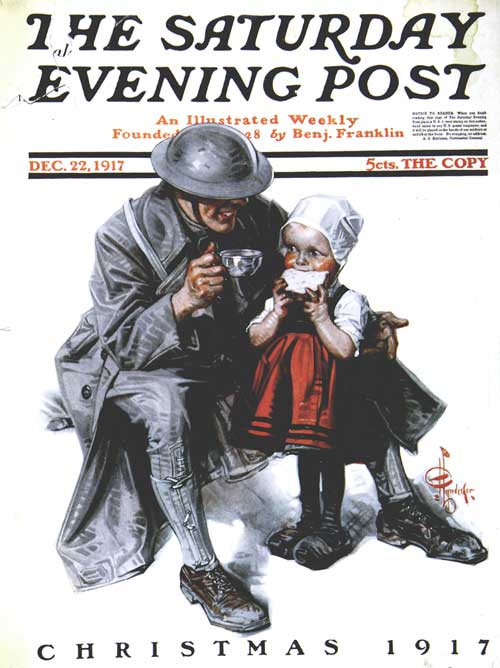

Christmas 1917

This painting by J.C. Leyendecker appeared on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post a hundred years ago today, December 22, 1917. The American soldier is sharing his meager Christmas meal with a French girl.