Shohola Tran Wreck of 1864

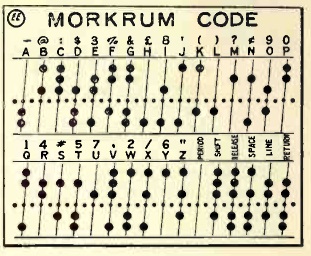

A hundred fifty years ago, the technology of the telegraph had been adopted by the railroads, and great reliance had been placed upon the device. And the Shohola train wreck of July 15, 1864, shows the horrific consequences apparently caused by one telegrapher’s negligence. On that day, at least sixty men died because the telegrapher failed to relay a message.

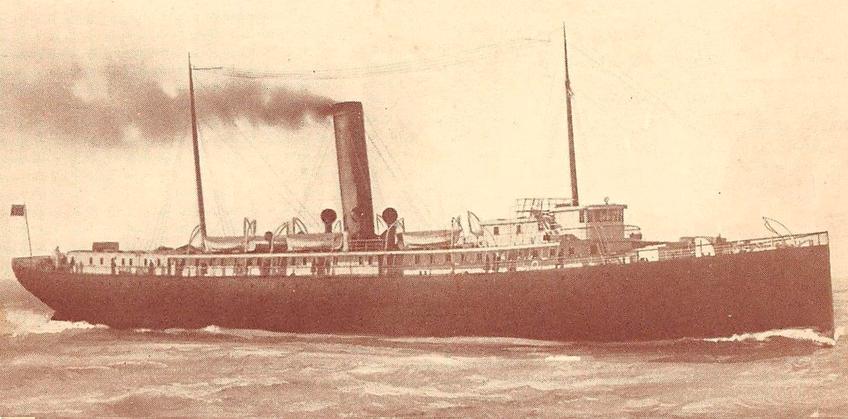

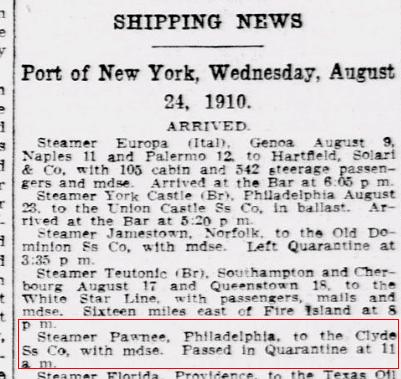

On that day, an 18 car train was transporting 833 Confederate prisoners of war, many of whom had been captured at the Battle of Cold Harbor. They were guarded by 128 members of the Union Veteran Reserve Corps. The train was travelling from from New York, where the prisoners had arrived by steamer from Maryland, to the prison at Elimira, New York.

The train was designated as an “extra,” meaning that it was not scheduled service, but instead followed behind a scheduled train. The scheduled train displayed flags which alerted that the extra was following, and continued to have the right of way.

The train with the prisoners had been delayed while guards located missing prisoners, and while it waited for a drawbridge. It was running four hours behind schedule by the time it got to Shohola, Pennsylvania. At about 2:45 PM, the train was on the single track between Shohola and Lackawaxen junction, proceeding at about 25 miles per hour.

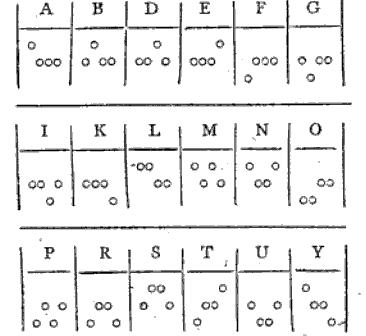

At Lackawaxen was stationed the telegraph operator Douglas “Duff” Kent. In the morning, he had seen the scheduled train pass with the warning flags, and it was his responsibility to hold all eastbound traffic until the extra train had passed. At about 2:30, a coal train arrived at Lackawaxen, and the conductor asked whether the track was clear to Shohola. The telegrapher, Kent, answered in the affirmative.

The trains were barely a hundred yards apart when the horrified engineers realized their predicament. There was no time for the engineers to even jump from the engine, and both were killed, along with the two firemen and one brakeman. In addition, 51 Confederate soldiers and 17 Union soldiers were killed. The Confederate dead included thirteen members of the 51st North Carolina Infantry. Two prisoners escaped and were never accounted for.

Most of the dead were buried alongside the track. The Confederate prisoners were buried in coffins hastily constructed from the lumber of the wreckage, four to a coffin. The Union soldiers were buried singly in pine coffins which had been brought to the scene. In 1911, all of the dead were exhumed and brought to Woodlawn National Cemetery in Elmira. The citizens of Shohola, Pennsylvania, and Barryville, New York, tended to the wounded “without regard to the color of their uniforms.”

Soon after the collision, Judge T.J. Ridgway arrived on the scene and impaneled a jury. An inquest was held and the burials proceeded. The verdict was that no railroad employee was to blame, and that the accident was unavoidable.

The New York Daily Tribune of July 18, 1864 noted that it was “desirable that something more than the sham investigation by the jury should take place.” The Daily Tribune reports that the telegraph operator is “said to have been intoxicated the night before, but until he can be met with, and the public will demand of the State authorities to see that he is, and can be confronted with the conductor of the coal train, it will not do to place too much reliance on the statement of the latter.

The Tribune continues, “it is the duty of each telegraph clerk to telegraph to the clerk at the next depot immediately the train has passed his station. At Lackawaxen were were unable to see the book kept by the absconding operator.”

And abscond he did. Other reports were that Kent “did not take the wreck very seriously,” and reportedly went to a dance that evening. When the public began to realize his role, he left town and was never seen again.

The Tribune’s reporter wrote:

Sadly familiar as the last three years have rendered the country and the public with tales of blood, scenes of slaughter, and the accumulated horrors of the battle-field, we are not yet so used to them as to feel unmoved when, on a smaller scale, some fearful railroad catastrophe brings them to us, face to face, amid the quiet of civil life. One of these terrible catastrophes, the most terrible that has happened in this country for some years, took place on Friday morning last, when the grave was again opened to receive a hecatomb of human life, offered at the shrine of managerial inefficiencyand subordinate recklessness.

References

The Great Shohola Train Wreck

Shohola Train Wreck at Wikipedia

Read More at Amazon:

![]()