75 years ago, American amateur radio operators were off the air for the duration, but QST kept rolling off the presses, and continued to encourage hams to hone their skills for the war effort. One skill, of course, where hams had a natural edge was their knowledge of the International Morse Code, which was widely used both in the military and by government and civilian radio stations.

In the June 1942 issue, long time QST Editor Clinton DeSoto, W1CBD, wrote this article about methods of visual signalling. He noted that many a young amateur “joined up with the Navy or the Sginal Corps secure in the belief that because he knew radio he knew all there was to know about communications.”

But DeSoto noted that knowledge of CW and radiotelephone, and even a smattering of wire telephone and telegraph, covered only a part of communications methods then in use. In many cases, radio was unavailable, such in cases where a ship had to observe radio silence, and wires were not always an option. Therefore, especially in the Navy, but also in the Army Signal Corps, a knowledge of visual signalling methods was critical.

In the article, he gives a primer on the methods then in use, and encouraged hams to learn these methods. Those methods were (1) aural; (2) blinker; (3) wigwag; (4) semaphore; and (5) the international flag code.

DeSoto noted that aural signalling would require little or no new knowledge for a ham, since copying Morse from a fog horn or siren was no more difficult than copying CW on the air.

Copying code from a light blinker required a bit of practice, since the ham had to use a different sense to transmit the signal to the brain. However, he noted that most hams could acquire a speed of 8-10 words per minute with just a few hours practice. This speed was quite useful, since 12 WPM was about the maximum ever encountered in blinker work.

The third method, wigwag, was rarely used, but since it was also based on International Morse Code, most hams would have an edge when it came to using it. In wigwag, a single signal flag or light is used. It is dipped to the left (from the viewer’s point of view) for a dot, and to the right for a dash. Between dots and dashes, the flag or light is held vertically above the head.

Wigwag is very slow and cumbersome, and had a maximum speed of a couple of words per minute. For that reason, it was rarely used except when nothing else would serve.

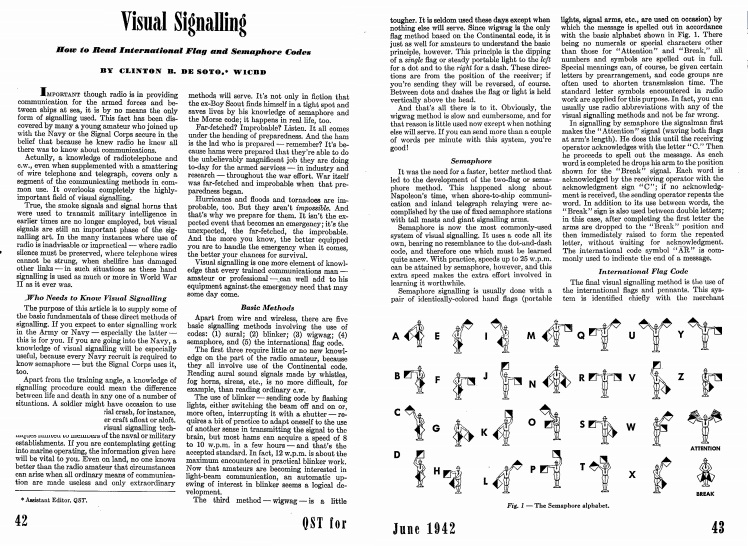

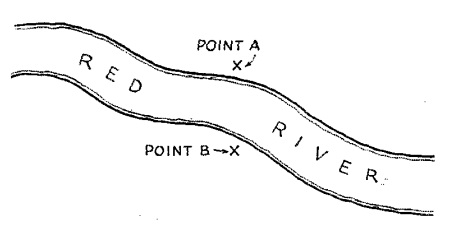

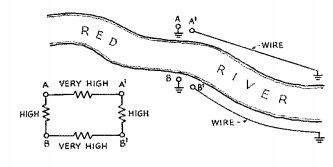

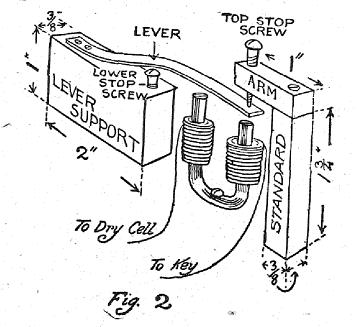

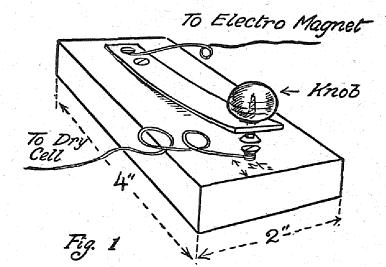

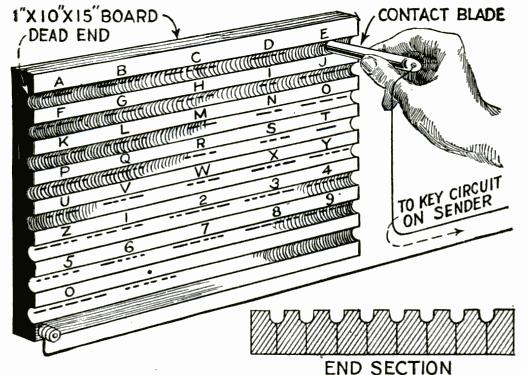

The much more efficient system of signalling with flags is semaphore, and DeSoto devoted much of the article to its explanation. As shown in the diagram above, semaphore uses two flags held in the positons shown above. Semaphore had been around since Napoleon’s day, and in addition to flags, shore-to-ship communication, and even inland links, of the past had used stations with tall masts and giant signalling arms.

With practice, a skilled operator could achieve speeds up to 25 words per minute, making semaphore a vitally useful skill.

The article gave the basics of the procedure used. To begin, the sender would wave the flags for the attention signal, until the receiving operator answered with the acknowledgment “C”. As the sender completed each word, he dropped his arms to the “break” signal. At that point, the receiver would acknowledge with another “C”. If no acknowledgement was received, that word would be repeated.

Some of the prosigns and abbreviations used by hams were also used in semaphore. For example, the symbol AR was commonly used to indicate the end of a message.

Finally, DeSoto spent some time discussing the international flag code, which used individual flags for each letter of the alphabet. Each flag also had an independent meaning. Therefore, if a single flag was displayed on the signal mast, it was understood that it was conveying that message.

To minimize the number of flags that had to be carried, four flags were assigned as “repeat” flags. The “First Repeat” flag would be used to indicate that the first letter of the word was being repeated. The “Second Repeat” flag would mean that the second letter of the word was being used again.

The international flags were reproduced in the article, but in black and white. DeSoto warned that it wouldn’t be a good idea to attempt to learn them from those illustrations. He recommended either coloring them on the pages of the magazine with water colors or crayons, or simply making a set of identification cards in the correct colors. He also included the source of flashcards, available for 50 cents postpaid, or the official “International Code of Signals (Vol. 1, Visual and Sound)” available from the Navy Department for $2.25. A more recent edition of that text is available at this link.

This article would be of particular interest to Boy Scouts or their counselors working on the Signs Signals and Codes merit badge. As I discussed previously at this post and this post, that merit badge includes Morse Code, semaphore, international flag codes, in addition to other topics. Therefore, DeSoto’s 1942 article includes much of the information necessary to earn the merit badge.

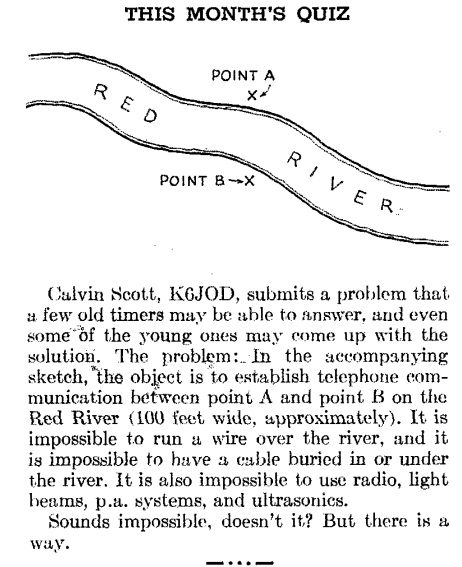

Elsewhere in the same issue of QST (page 53), ARRL Communications Manager F.E. Handy, W1BDI, suggested a use for the signal flags. With amateur radio off the air, there would be no Field Day in 1942. Handy suggested that hams could use the traditional Field Day weekend, the third weekend in June, to make an outing to their usual Field Day location to practice some of these techniques:

Working in pairs, amateurs should call out characters as they are interpreted from the flags, impressing a bystander for ‘recorder’ if necessary. With some experience you will with to try for greater DX. Then we also suggest a planned trek to the usual FD location if you can make it on that third weekend of June. This will make a good outing for those of the group that can be rounded up; it will rouse afresh the memories of the last ARRL Field Day. Don’t forget to give the signal-flag idea a Field Day workout!