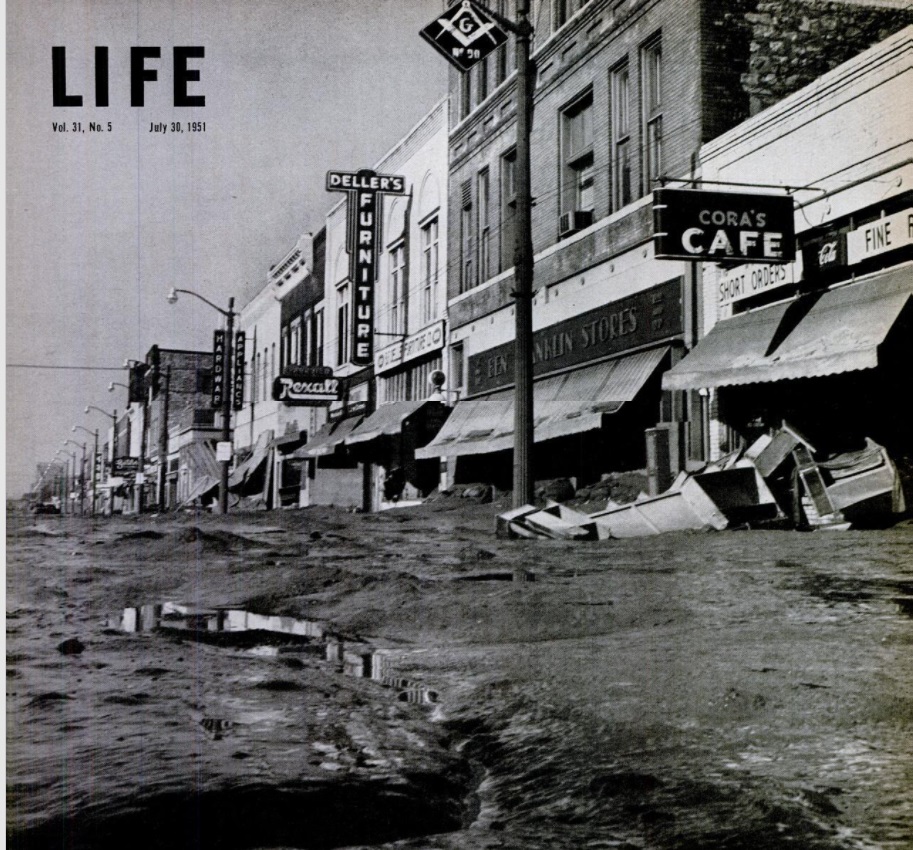

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the Great Flood of 1951 along the Kansas and Missouri Rivers. With 17 deaths and almost a billion dollars in damage, the flood was the nations then-costliest natural disaster.

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the Great Flood of 1951 along the Kansas and Missouri Rivers. With 17 deaths and almost a billion dollars in damage, the flood was the nations then-costliest natural disaster.

The photo above shows downtown North Topeka, Kansas, from the July 30, 1951, issue of Life magazine.

According to the November 1951 issue of QST, much of the Amateur Radio response to the flood focused around the U.S. Naval Reserve. Station K0NRZ at the Naval Reserve Training Center in Topeka maintained a continuous watch on local emergency frequency 29.5 MHz from July 11 to 15. On the 15th, a long-haul net was established on 7042 kHz and handled over 1000 messages through July 20.

One ham reportedly furnished handie-talkies (3885 kHz) which were used for communication between Army/Air Force trucks and Coast Guard boats engaged in sandbagging the levees.

The QST October issue also reported that the station K0NAB at the Naval Air Station in Olathe, KS, handled radio traffic for Western Union, whose lines were out.