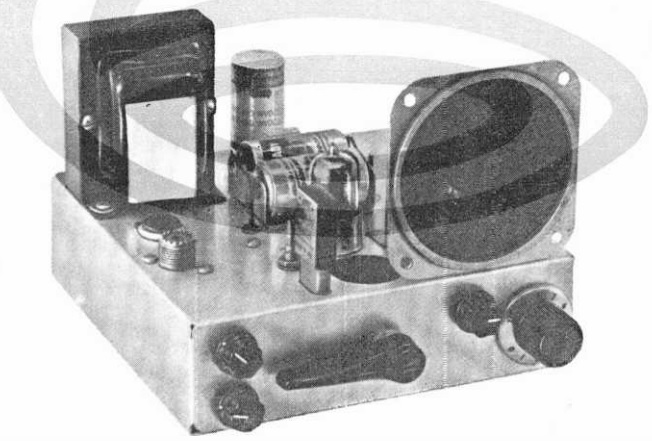

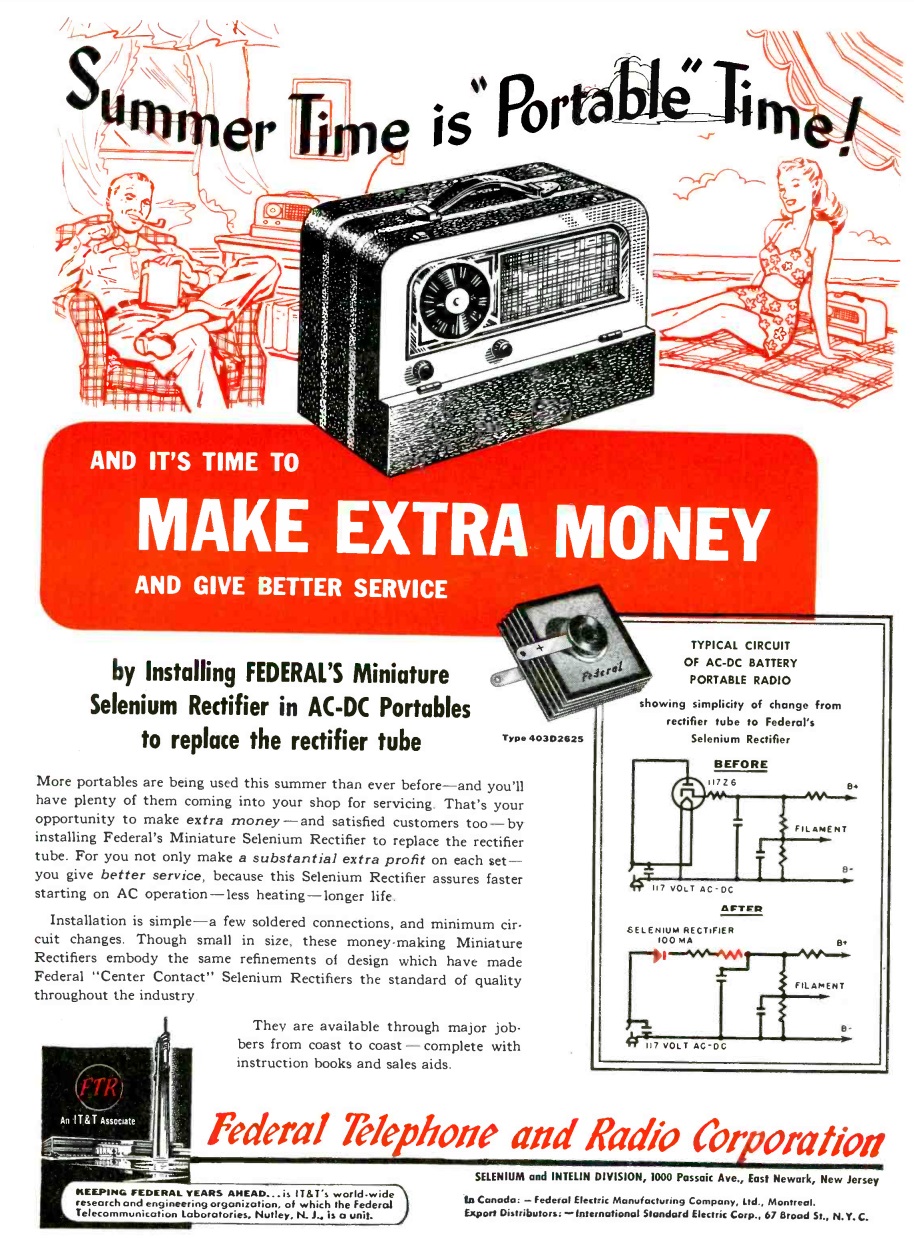

Seventy-five years ago, if you wanted to be the first on your block with a receiver for the new postwar FM band, you couldn’t go wrong with the Model FM-7 receiver kit from the Radio Kits Company, 120 Cedar Street, New York.

Seventy-five years ago, if you wanted to be the first on your block with a receiver for the new postwar FM band, you couldn’t go wrong with the Model FM-7 receiver kit from the Radio Kits Company, 120 Cedar Street, New York.

The set was complete with speaker, but there was also provision to use the set as a tuner to feed a separate hi-fi amplifier. The RF section was pretuned at the factory.

This ad appeared in the August 1947 issue of Radio Craft. You can find a schematic of the set at this link.

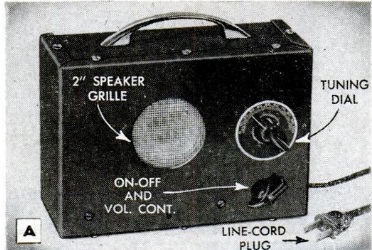

And if you want to put together your own FM radio today (and practice your soldering skills at the same time), you can’t go wrong with the Elenco kit shown here.

And if you want to put together your own FM radio today (and practice your soldering skills at the same time), you can’t go wrong with the Elenco kit shown here.

And if Junior wants in on the fun, then the Snap Circuits FM receiver shown below can be put together by kids of any age. The manufacturer recommends it for kids over 8 years old, but as long as Junior knows not to eat the parts, it should be fine.

Some links on this site are affiliate links, meaning that this site earns a small commission if you make a purchase after using the link.

Get Eclipse Glasses for the 2024 Eclipse!

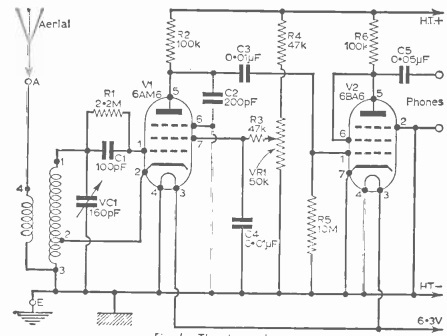

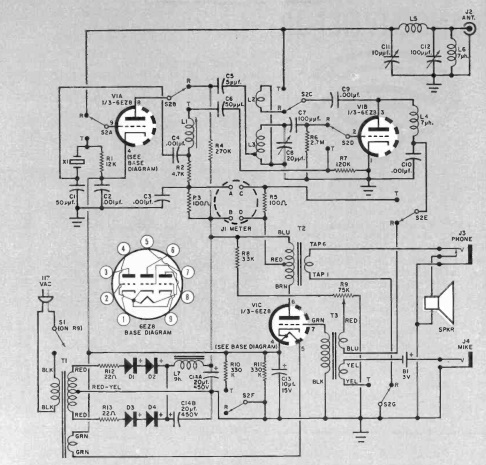

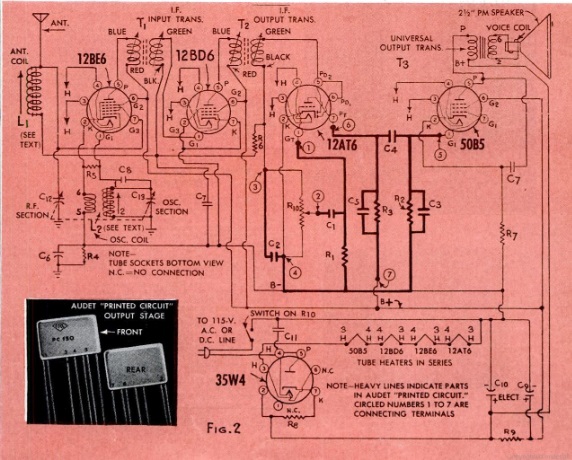

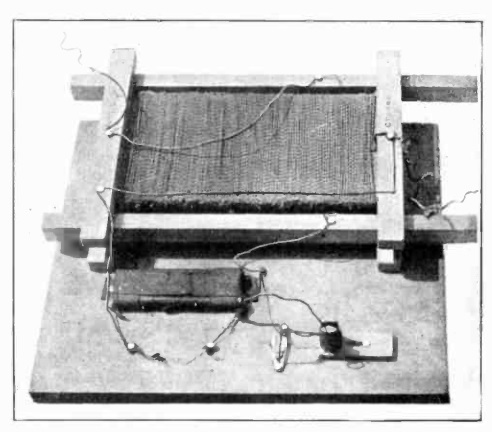

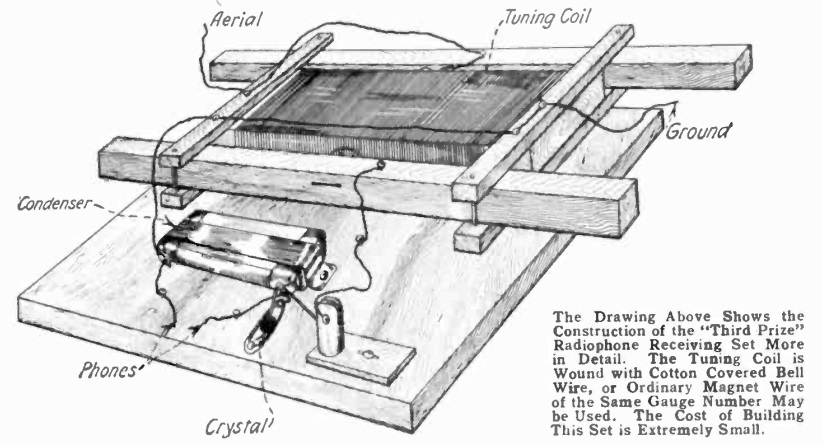

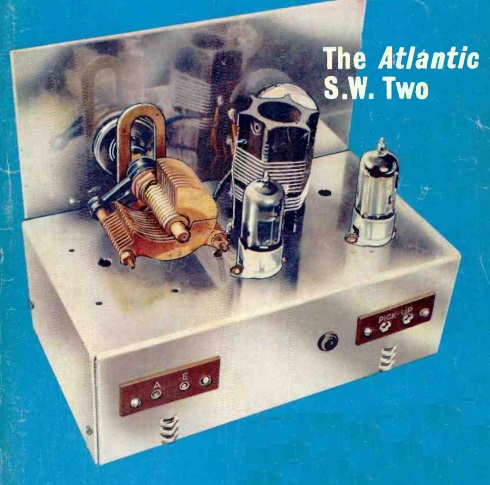

Sixty years ago this month, the August 1962 issue of the British Practical Wireless carried the plans for this handsome set, dubbed the “Atlantic S.W. Two” The two-tube regenerative set was designed for 15-40 meters, but with plug-in coils, the range could be extended. It was said to give good performance and was easy to construct. Also shown was an AC power supply, with transformer, which kept the headphones isolated from the high voltages, and rendered the set safe.

Sixty years ago this month, the August 1962 issue of the British Practical Wireless carried the plans for this handsome set, dubbed the “Atlantic S.W. Two” The two-tube regenerative set was designed for 15-40 meters, but with plug-in coils, the range could be extended. It was said to give good performance and was easy to construct. Also shown was an AC power supply, with transformer, which kept the headphones isolated from the high voltages, and rendered the set safe.