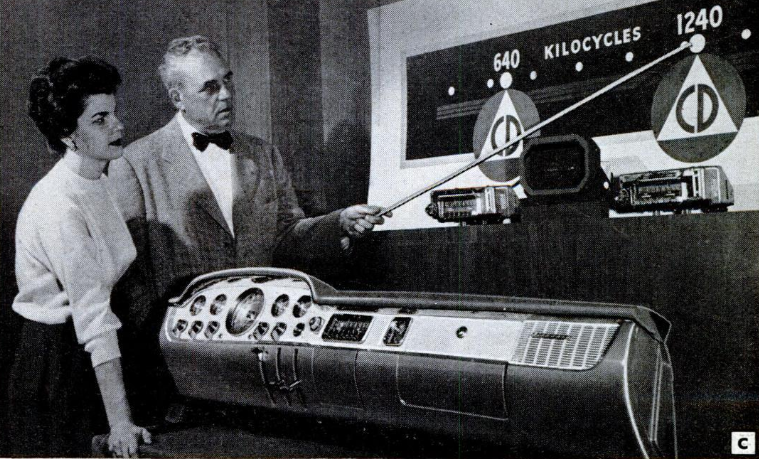

Sixty years ago, there was no better way to impress the chicks than installing a CB radio in your sportscar, as demonstrated here by one Dave Hallow, KLK6733. We have a hunch, however, that he’s actually shown here with his kid sister. In any event, the car was an Austin-Healy Sprite, and Hallow needed to figure out how to install a CB without disturbing the lines of the car. He accomplished this, first, by replacing the existing AM antenna with an Antenna Specialists M-103 combination AM-CB antenna. Since there was no room under the dash, he installed an E.F. Johnson M-III transistorized transceiver under the dash, along with a Johnson suppression kit to eliminate interference.

Sixty years ago, there was no better way to impress the chicks than installing a CB radio in your sportscar, as demonstrated here by one Dave Hallow, KLK6733. We have a hunch, however, that he’s actually shown here with his kid sister. In any event, the car was an Austin-Healy Sprite, and Hallow needed to figure out how to install a CB without disturbing the lines of the car. He accomplished this, first, by replacing the existing AM antenna with an Antenna Specialists M-103 combination AM-CB antenna. Since there was no room under the dash, he installed an E.F. Johnson M-III transistorized transceiver under the dash, along with a Johnson suppression kit to eliminate interference.

He’s shown wearing a Telex DYB-10 boom microphone headset to allow hand-free communication. The photo appeared in the February 1965 issue of Popular Electronics, which noted that the headset provided the ability to receive clear signals above 40 MPH. Perhaps regulators hadn’t gotten around to re-writing traffic codes yet, but a dual headset for the driver would be illegal in most states today, since it doesn’t allow road noises to be heard. These days, single-ear Bluetooth headsets, complete with noise-cancelling mike, are available.

We asked ChatGPT to write a story based upon this picture. I don’t think we have to worry about job security–just yet. But here’s ChatGPT’s take on it:

The Radio Roadtrip

In the summer of 1965, young Tommy had a dream–to make the ultimate road trip using nothing but his wits, his radio, and his dad’s old convertible. His little sister, Sally, wasn’t about to be left behind, even though she wasn’t quite sure what “ham radio” even meant.

“Are you sure you can drive this thing?” Sally asked, gripping the side of the car as she climbed in.

Tommy, adjusting his oversized headset and pushing his glasses up the bridge of his nose, gave her a confident nod. “Of course! Well… kinda. But that’s not the point. The point is, we’re gonna talk to people all over the world—while driving!”

Sally giggled, excited despite herself. “Like astronauts?”

“Exactly! Or people in Australia! Or maybe even spies! Who knows?” Tommy grinned as he flipped a few switches on the makeshift radio setup he had wired into the dashboard. The soft crackle of static filled the car, and then a voice came through—

“CQ, CQ… this is W6XYZ. Anyone out there?”

Tommy’s eyes widened. He quickly grabbed the microphone. “W6XYZ, this is Tommy—uh, I mean, this is K0TOM, mobile unit, coming in loud and clear!”

Sally clapped her hands. “It works! It really works!”

Their adventure had begun.

Would they make contact with a scientist in Antarctica? A pilot flying high above the clouds? Or maybe even a fellow kid with a radio of their own? One thing was for sure—this was going to be a summer to remember.

Some links on this site are affiliate links, meaning that this site earns a small commission if you make a purchase after using the link.

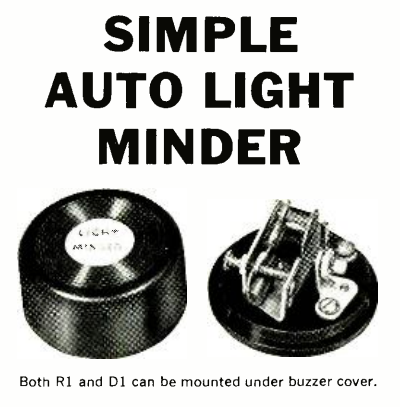

Sixty years ago this month, the May 1965 issue of Popular Electronics showed this simple circuit for a headlight reminder. I remember that starting in the 1970s, cars started including a noisemaker to remind you of various things, such as not wearing your seat belt. But the one helpful thing it could be used for would be to prevent leaving your headlights turned on.

Sixty years ago this month, the May 1965 issue of Popular Electronics showed this simple circuit for a headlight reminder. I remember that starting in the 1970s, cars started including a noisemaker to remind you of various things, such as not wearing your seat belt. But the one helpful thing it could be used for would be to prevent leaving your headlights turned on.