These days, we tend to take for granted the availability of amplified sound systems. If you’re going to make a speech before a large auditorium, the first matter of business is to turn on the sound system and locate the microphone.

These days, we tend to take for granted the availability of amplified sound systems. If you’re going to make a speech before a large auditorium, the first matter of business is to turn on the sound system and locate the microphone.

But there was a time, not so long ago, that electronic sound amplification didn’t exist. A hundred years ago, if you were going to be a preacher, a politician, or some other kind of public speaker, then you had to learn how to project your voice. If the people in the back row couldn’t make out your voice, then they weren’t going to hear the Gospel, they weren’t going to vote for you, or they weren’t even going to hear what you had to say. When Theodore Roosevelt gave his “big stick” speech in 1901 at the Minnesota State Fair, hundreds of people heard him because he used a big voice to deliver it.

But there was a time, not so long ago, that electronic sound amplification didn’t exist. A hundred years ago, if you were going to be a preacher, a politician, or some other kind of public speaker, then you had to learn how to project your voice. If the people in the back row couldn’t make out your voice, then they weren’t going to hear the Gospel, they weren’t going to vote for you, or they weren’t even going to hear what you had to say. When Theodore Roosevelt gave his “big stick” speech in 1901 at the Minnesota State Fair, hundreds of people heard him because he used a big voice to deliver it.

It was only in the 20th century that public speaking came to be associated with electronic amplification. As we’ve previously reported, for example, Notre Dame cathedral was first wired for sound in 1925. And when the Iowa legislature was getting a sound system in 1939, it was probably about the same time as other legislative chambers.

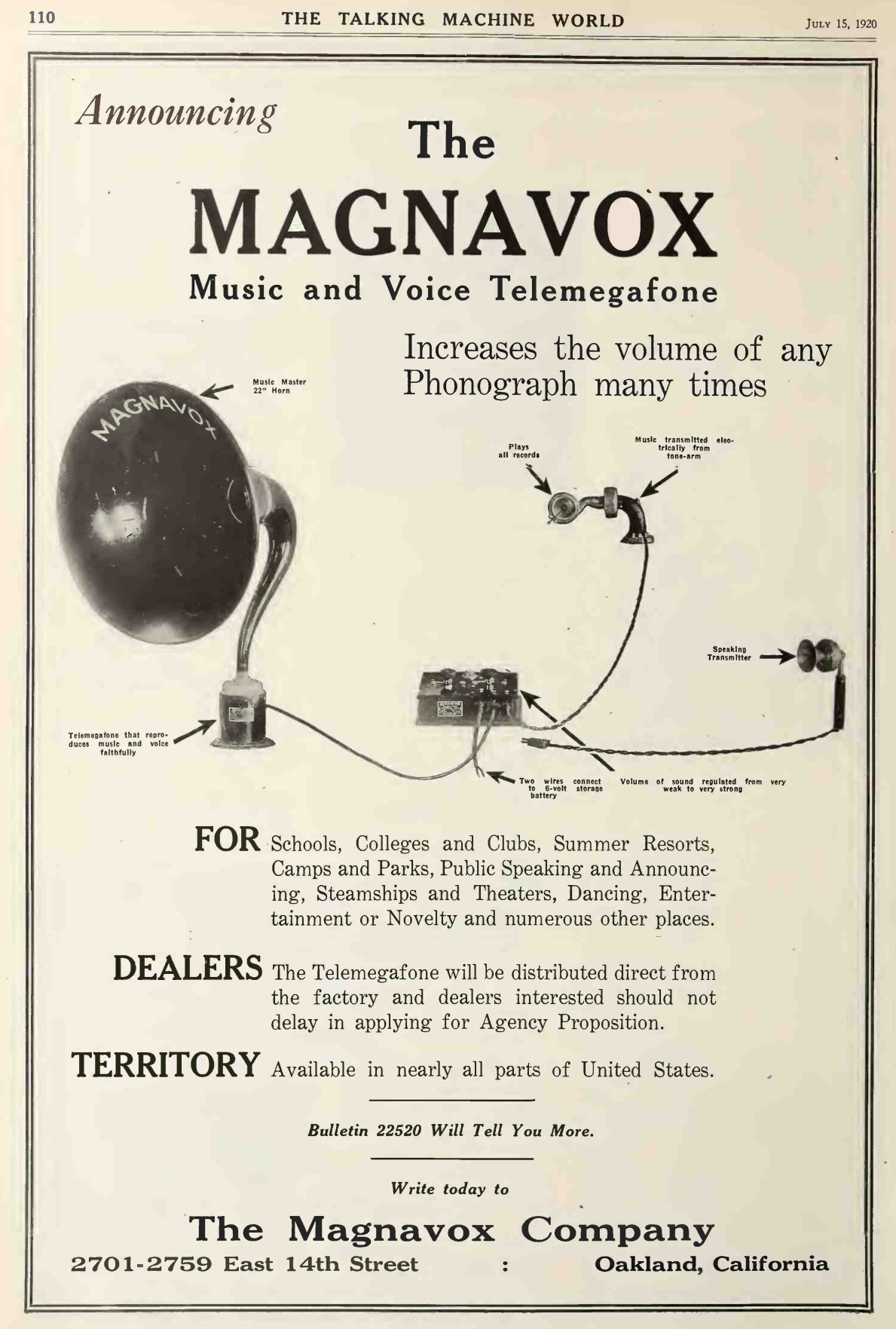

One of the first examples of an electrical sound system comes from Talking Machine World a century ago this month. This particular system wouldn’t have been of much use to preachers or politicians trying to be heard in a large auditorium, but it’s an early example of what would be perfected within a few years. The Magnavox Telemegafone system shown here could be used with a phonograph, or with what we would today call a microphone, although that term hadn’t been coined.

I describe this as an “electrical” system rather than “electronic,” because there doesn’t appear to be any electronic amplification. The microphone is probably a carbon mike, and the phonograph transducer probably is as well. They drive the speaker directly. The speaker does not have a permanent magnet. Instead, it has a field coil powered by a 6 volt battery.

One of the described purposes is as a “novelty,” and a speaker who could project his voice well would probably be better off not bothering. But within just a few years, the idea of electronic sound would become popular, and the profession of “sound man” would be born. And a century later, we would take for granted that to speak before a large audience, we need to find the microphone and turn on the P.A.