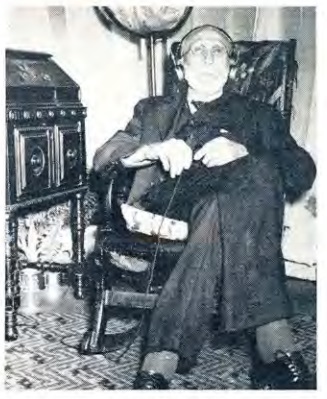

Shown here is Dr. William Eberle Thompson of Bethel, Ohio. The 104-year-old doctor is wearing headphones and listening to WLW radio. The photo was taken on the occasion of an interview by Ed Mason, WLW Farm Events Announcer, who wrote about the interview in the May 1939 issue of Rural Radio magazine. Mason noted that he “interviews some mighty interesting and important people. But never have I talked to anyone who could match this country doctor who voted twice for Lincoln.”

Shown here is Dr. William Eberle Thompson of Bethel, Ohio. The 104-year-old doctor is wearing headphones and listening to WLW radio. The photo was taken on the occasion of an interview by Ed Mason, WLW Farm Events Announcer, who wrote about the interview in the May 1939 issue of Rural Radio magazine. Mason noted that he “interviews some mighty interesting and important people. But never have I talked to anyone who could match this country doctor who voted twice for Lincoln.”

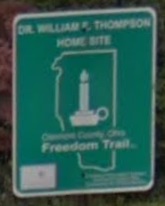

While the magazine article is lacking in details, the centenarian doctor is almost certainly the same person described in the book The Underground Railroad: An Encyclopedia of People, Places, and Operations. In addition to merely voting for Lincoln, Dr. Thompson played a much greater role in ending slavery. “In his youth, the family’s two-story brick residence at 133 South Main Street was a safehouse. In adulthood, his home and office at 213 East Plane Street received refugees.” The Rural Radio article mentions that Dr. Thompson’s “hands and eyes, now weary from service to his neighbors, had brought him fame as a crack shot with his old muzzle-loading rifle.” The old muzzle loader had been put to good use, since “to secure slaves in flight from posses, Thompson shot their bloodhounds.”

According to this site, Dr. Thompson became an active member of the Bethel Underground Railroad network as a teen. He guided fugitives from Bethel to the Elklick area near Williamsburg. He practiced medicine in the community for eight decades and was active in village government and social affairs.

The headphones in the photo were a gift, as explained in the magazine article:

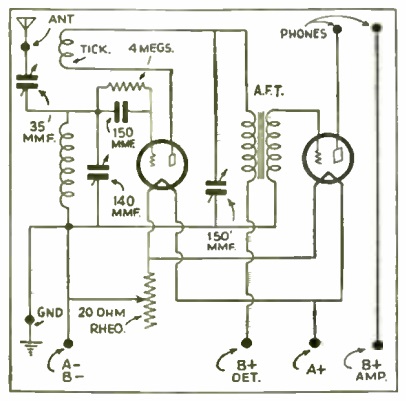

Long after the switch had been turned which took us off the air, we talked. I learned that he liked to listen to the radio, and especially news broadcasts, but his hearing had failed and he had not used his radio for several years.

When Phil Underwood, WLW engineer, heard this, he opened that magic box that a radio engineer always carries. He brought out headphones, special amplifiers, wires and switches. When we left, Dr. Thompson was sitting by his radio hearing distinctly for the first time in years hearing news by the magic of radio.

The Rural Radio article refers to the doctor as “C. Eberle Thompson.” This is almost certainly an error, since it’s unlikely that there was another centenarian doctor in the same small town. Dr. Thompson died in 1940, a few months shy of his 105th birthday. He continued to practice medicine until about a month before his death.