Eighty years ago, the October 1937 issue of Popular Science showed the aspiring young scientist how to perform the “most mysterious and beautiful of chemical experiments” by producing substances that glow in the dark. Fortunately, all of the materials required are readily available today. In fact, the young Einstein will probably discover that most of them are already in the kitchen or garage.

Eighty years ago, the October 1937 issue of Popular Science showed the aspiring young scientist how to perform the “most mysterious and beautiful of chemical experiments” by producing substances that glow in the dark. Fortunately, all of the materials required are readily available today. In fact, the young Einstein will probably discover that most of them are already in the kitchen or garage.

While the effect is not as strong as with other chemicals, many of these glow-in-the-dark formulas can be prepared with items already in the kitchen. Among these was chili powder (the stronger the better). The magazine noted that “a single can of chili powder from the grocery store will be enough for innumerable experiments.” Paprika, as well as other items, could also be used. Mom will be happy to learn that it was a “fascinating pastime to try out a little of everything on the pantry shelf, to see what substance will give the strongest light.”

To make these household substances glow, it was necessary first to steep a little alcohol on the item. Then, you would add some lye and hydrogen peroxide.

The final ingredient was new in 1937, judging from the explanation: “One of the newer, ‘made with electricity’ bleaching liquids and laundry whiteners. There are several of these liquids, widely advertised and obtainable at any grocery store. They are solutions of sodium hypochlorite, and you will find that this statement appears on the labels of the bottles.”

Eighty years later, we just call this “household bleach,” and the most famous brand name is Clorox.

For a stronger effect, the article recommended substituting the chili powder with oil of bergamot, which was available at the drug store. I don’t know if you can find it at the drug store today, but as with everything, it’s available at a reasonable price on Amazon, at this link. According to the Amazon description, this “essential oil” (I’ve always wonder why nobody uses non-essential oils) is “helpful in soothing the mind and body with aromatherapy” and is safe for topical application. But it’s a lot more fun if you get it to glow in the dark.

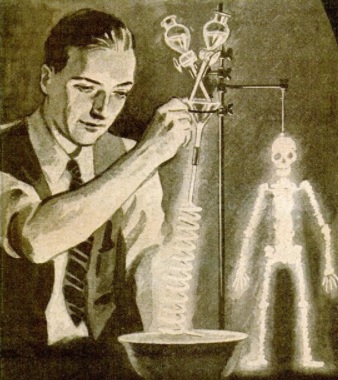

For the strongest effect, the article recommended 3-aminophthalhydrazide, more commonly known as luminol (according to the article, not to be confused with luminal, a barbiturate drug). It’s also available from Amazon at reasonable price at this link. With this chemical, spectacular displays, such as the ones shown at the top of the page, are possible.

The article includes even more suggestions for glow-in-the-dark experiments. The young scientist looking for something spectacular for the next science fair will undoubtedly find much inspiration from this old article.