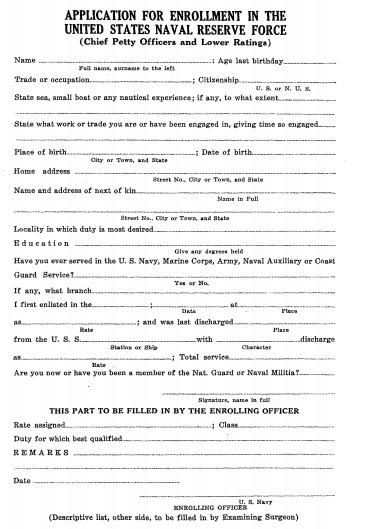

A hundred years ago, Uncle Sam was looking for amateur wireless operators, and the ARRL was doing everything within its power to make sure the need was met. The July 1917 issue of QST came complete with the application blank necessary for young hams to sign up:

It was explained that applicants were to take the filled in enrollment form to their nearest Navy Recruiting Office. (If they didn’t know where it was, ARRL HQ could provide the address.) At the recruiting station, the officer there was to certify the applicant’s physical condition. Then, the applicant would return the form to ARRL HQ, which would send it to the proper headquarters. “They will notify you when and where to report.”

The accompanying article explained that 2000 wireless operators were needed by the Naval Reserve. “At the outset all will probably agree that this is a call of humanity and before it is over every one of us will have to play his part. To play your part and do your bit,–does not mean you must shoulder a gun. Your part if you are a radio operator is to serve in that capacity. Your duty is to enroll today. Uncle Sam must have wireless operators. You must not fail him in this hour of need.”

The article explained that enlistment was for the duration of the war, and that reservists would be able to ask for discharge during times of peace. It stressed that enlistment would give one of the finest educational courses in the country, comparable to a college education.

Two schools were in operation by the Navy. Harvard University had turned over to the Navy Pierce Hall, in which at present 150 radio electricians were being trained. A smaller school was in operation at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. And as enlisted man, the recruit would have the opportunity to enter the Naval Academy by examination. Pay ranged between $32.60 and $72.00 per month, plus uniform and subsistence.

Two schools were in operation by the Navy. Harvard University had turned over to the Navy Pierce Hall, in which at present 150 radio electricians were being trained. A smaller school was in operation at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. And as enlisted man, the recruit would have the opportunity to enter the Naval Academy by examination. Pay ranged between $32.60 and $72.00 per month, plus uniform and subsistence.

An accompanying editorial, probably written by Hiram Percy Maxim, admonished “hurry up and enroll.” The Old Man notes that the “engineering course given is unquestionably one of the finest things offered in this country in the way of a practical training in electrical engineering.”

After mentioning the pay, the Old Man opines that “any amateur radio operator who does not take advantage of it ought to have his head examined.”

The editorial concludes by admonishing young men to think it over, “and make Mother and Father read this editorial.”