Seventy years ago, the January 1947 issue of Boys’ Life contained some career advice for scouts looking for excitement:

Becoming “Sparks,” a radio officer in the Merchant Marine. The article’s author was Merceant Marine radio officer Lt. Robert Aronson, who noted that as ears and mouth of the ship, the position was one of rank and responsibility.

The most important job was to maintain a constant watch on the international distress frequency, 500 kilocycles. Other duties included a daily check of the radio room batteries with a hydrometer, and checking the traffic lists of the coast stations for any incoming messages.

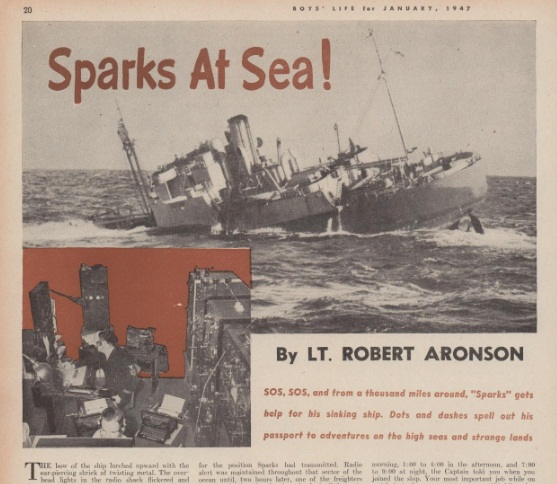

And, of course, the job offered plenty of opportunities for heroism. The article begins with the tale of a radio operator firing up the transmitter of the ship in distress, and within moments having every ship within 800 miles prepare to rescue. “Radio alert was maintained throughout that sector of the ocean until, two hours later, one of the freighters announced triumphantly that she had all forty-six of the crew aboard, uninjured. Once again, a capable ‘Sparks’ had blocked off a watery grave.”

The job offered a lot of spare time to read, play cards, study, or anything else. The author noted that many radiomen found the life at sea ideally suited to advancing their knowledge of radio or any other subject.

The author’s advice for scouts contemplating this career was to get their ham license, a license only “slightly lower in grade and requirements than a commercial operator.” With the amateur license, the scout could set up his own station and communicate just as though he were on a ship.

The commercial license could be acquired by enrolling in a school, but for the student who could read a textbook and absorb the instructions, he pointed out that there was no reason not to engage in self-study. The amateur license would allow the student to practice the things taught by the books, and those books were available in any public library.

The prospective operator would be eligible for a commission as an officer six months after signing on to a ship, and at that time, the government made available excellent correspondence courses.

The author noted that the commercial license was the passport to adventure, but cautioned against hastily going to sea, especially if one had a “flaring temper or if you sulk, if doing the same thing day in and day out gets you down.” For prospective radio operators who fit those descriptions, he advised that one of the many radio jobs ashore might be better suited.