Seventy-five years ago, American broadcasters were gearing up for some big changes in 1941. The engineers were busy ordering crystals and getting ready to retune their transmitters on March 29, 1941, to the new frequencies mandated by NARBA.

But the program director had even bigger things to worry about, because of the ASCAP Boycott, which was to start on January 1, 1941, and would last until October 29, 1941.

The American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) was formed in 1914 to enforce the 1897 copyright law. In the days of live performances, this had been easy, since the royalties were just based on a percentage of the box office sales. But the phonograph, and later radio, complicated things considerably. But after almost a decade of haggling, a tenuous truce was in place between ASCAP and the broadcasters. The stations grudgingly agreed to pay 5% of advertising revenue in exchange for a blanket license to perform all ASCAP music. But the truce didn’t last long, and in 1940, worried that radio performances were cutting in to phonograph sales, ASCAP announced that it was going to triple the broadcast fee. The broadcasters decided that enough was enough, and at the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) convention, the broadcasters decided that they would boycott ASCAP. Therefore, as of January 1, 1941, most of the stations’ existing music libraries could not be used. This included both recorded music and the sheet music used in the still common live performances by orchestras and studio pianists and organists.

Virtually every part of a station’s programming was affected. Even most program theme songs were controlled by ASCAP and had to be changed. Jack Benny had to stop playing his signature “Love in Bloom” on the violin, and Burns and Allen had to stop using their theme “Love Nest,” written by ASCAP co-founder George M. Cohan.

Jeanie in 1854, before her hair turned gray. Wikipedia image.

The stations had two alternatives, and had to act fast. First, they could make use of public domain material. This is why the Lone Ranger rode to the tune of the public domain William Tell Overture, and the Green Hornet flew to the music of The Flight of the Bumblebee. One notable beneficiary on stations’ play list was “Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair,” penned by Stephen Foster in 1854. Time magazine quipped that the song had received so much airplay that Jeanie’s hair turned gray.

Stations also turned to foreign music such as “Perfidia.” And since ASCAP had generally believed that “hillbilly” and African-American music were beneath their dignity, these genres quickly found a home on the American airwaves.

In order to get radio airtime, performers had to make the same choices. It’s no coincidence that Glenn Miller’s orchestra made 1941 hits with “American Patrol” and “Song of the Volga Boatmen,” both in the public domain.

For new music, broadcasters turned to the fledgling Broadcast Music International (BMI), a rival licensing agency founded by the broadcast industry in 1939. BMI recruited composers whose ASCAP contracts were about to expire as well as new composers, and made these available to broadcasters on more favorable terms.

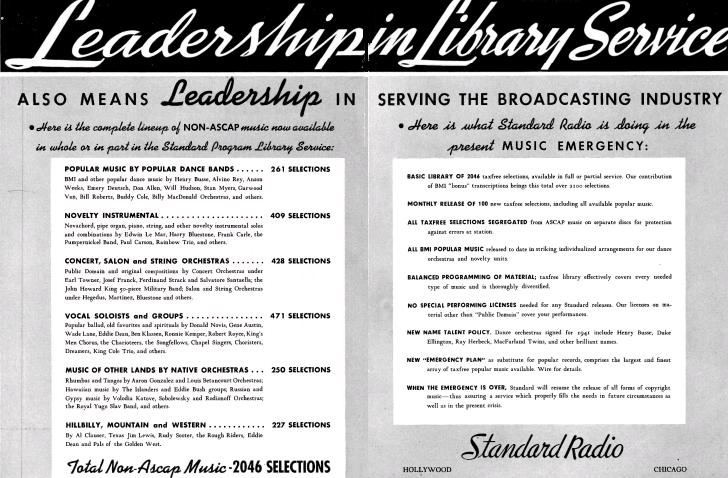

A substantial portion of the December 15, 1940, issue of Broadcasting magazine was devoted to helping broadcasters gear up for the boycott. For example, the ad at the top of this page Standard Radio touted, during the “music emergency,” its music library of 2046 non-ASCAP taxfree selections including performances by artists such as Duke Ellington and Ray Herbeck, with the promise of 100 new releases per month.

An editorial in the same issued called it a war, not unlike the war raging in Europe: “Zero hour approaches in the war over music. War is hell in any language, and there are hellish days ahead for the adversaries in the conflict precipitated by a hitherto arrogant, brass-knuckled ASCAP that now must know it overplayed its hand. The rank and file broadcaster is not thinking about an ASCAP deal. Like the Italians, ASCAP attacked with untenable demands. And like the Greeks, the broadcasters are on the march.”

And in this war, the broadcasters knew that ASCAP would be ruthless. Every broadcaster knew that the ASCAP lawyers would retaliate heavily for even the most innocent minor violation. The broadcasters had to ensure that not one note of an ASCAP-licensed competition could go out over the airwaves.

The magazine carried the advice sent out by CBS to its affiliates about the steps that needed to be taken to avoid even an accidental infringement of any ASCAP music. It stressed that the program producer or director had to personally inspect “all music on the conductor’s stand against his certified music sheet. No other music may be broadcast.” It stressed that it was particularly important to be careful with remote broadcasts. And for protection in case of later accusations, it was especially critical to keep a meticulous log of all music broadcast.

And dead air was better than an ASCAP lawsuit, so “the program producer must have the right to pull the plug on the slightest deviation from a certified music schedule.”

Ad libs and improvisations were not to be allowed. “If it isn’t on paper and certified, it is not be be broadcast.” And stations couldn’t forget that last-minute substitutions of talent might be required. “All staff artists, organists, and pianists, who might be required to fill in, must clear a sufficient number of work sheets to meet such needs.” Organists on dramatic shows would need to immediately submit a folio of cue music sufficient for their needs and be reminded that no other music could be played unless it had been cleared.

Even at non-musical remotes, the stations would have to be careful. If a station knew that music might be played in the background at a baseball game or political rally, it was not to be picked up. Since most band music was controlled by ASCAP, “the chances are we will have to forego those portions of a special event during which the band is playing, unless you can build and work from a soundproof booth.”

All recordings would have to be checked, and the ASCAP material be put away for the duration of the emergency. If a record had an ASCAP song on one side and a non-ASCAP song on the other, then tape would need be placed over the infringing side to keep it from being accidentally played. Even the emergency records kept at the transmitter site would need to be checked. A failure of the studio to transmitter link could not be allowed to serve as a reason for the ASCAP lawyers to swoop in.

The magazine also contained some good news. There were already 3400 records licensed by BMI would could be safely played. The magazine also announced the signing of a contract between BMI and the Edward B. Marks Music Corp., shown here, transferring that publisher’s catalog of over 15,000 songs to BMI. This freed up such compositions as “Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight” and “Ta Ra Ra Boom Der Ay” for broadcast. Benny Goodman’s theme song, “Let’s Dance” was among those included in the Marks deal.

The magazine also contained some good news. There were already 3400 records licensed by BMI would could be safely played. The magazine also announced the signing of a contract between BMI and the Edward B. Marks Music Corp., shown here, transferring that publisher’s catalog of over 15,000 songs to BMI. This freed up such compositions as “Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight” and “Ta Ra Ra Boom Der Ay” for broadcast. Benny Goodman’s theme song, “Let’s Dance” was among those included in the Marks deal.

References

Read More at Amazon

The following songs in this post are available at Amazon where you can listen to a free sample or download the MP3:

- Love In Bloom, Jack Benny

- Love Nest, Burns & Allen

- Jeanie With The Light Brown Hair

- Perfidia, Glenn Miller

- American Patrol, Glenn Miller

- Song Of The Volga Boatmen, Glenn Miller

- Ta-Ra-Ra-Boom-Der-Ay

- Let’s Dance, Benny Goodman

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

![]()