If the project shown in this photo looks dangerous to you, well, that’s probably because it is dangerous.

WARNING: Do not construct the worm shocker shown on this page! This is not a construction article. It is an interesting historical look back at an earlier time when people didn’t worry quite so much about things like electrocution.

If you ignore my advice, don’t sue me if something goes wrong (and that goes for your heirs, as well).

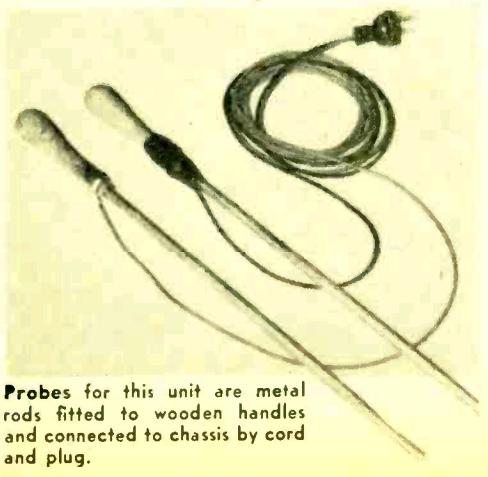

This illustration appears in the 1958 edition of the Electronic Experimenter’s Handbook, published by Popular Electronics. It is exactly what it appears to be, namely, an AC line cord attached to two metallic probes. One of the probes has rubber tape near the wooden handle. The other one has not yet received this gesture toward safety.

Another warning: If you insist on building this contraption, you must not plug this probe directly into an outlet. It is plugged into a circuit which provides a small amount of safety. If plugged directly into household current, it would be positively lethal, instead of just extremely dangerous. (In fact, if you insist on doing this, it would be a good idea to use a plug rated at 120 volts, but one that does not fit into the normal household outlets, lest someone sees this one part and decides to plug it in to see what it does.)

With all of my earnest warnings out of the way, I’ll disclose what this is. It isn’t a torture device, at least not one for humans. It’s actually part of a worm catcher, a labor-saving device that will bring earthworms to the surface for easy collection. It does so by sending household current through the soil. You stick the probes into the ground, about 3 feet apart, and then plug the probes into the accompanying power supply (and not directly into a wall outlet). The worms will experience the discomfort of electrical current passing through them, and in an effort to escape, they’ll come to the surface where you can harvest them.

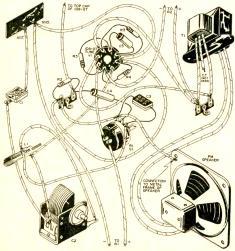

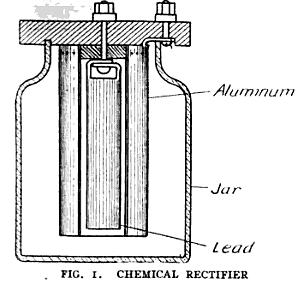

The accompanying article describes two power supplies. The first one consists of little more than two ten-watt light bulbs, one in series with each side of the AC line. The whole circuit is mounted in a wooden box. “Wood was used in this case because of its insulating properties.”

This circuit will undoubtedly trip a modern GFCI outlet. (And by code, any outside outlet should be protected by a GFCI.) Therefore, it probably wouldn’t work today. I’m not going to explain why it wouldn’t work. If you don’t know, then you should definitely not build either of these until you’ve brushed up on your electrical theory.

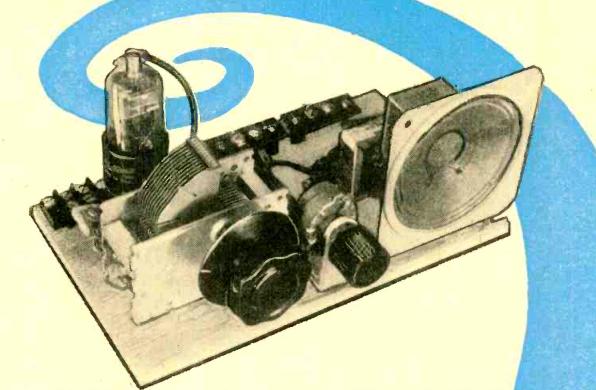

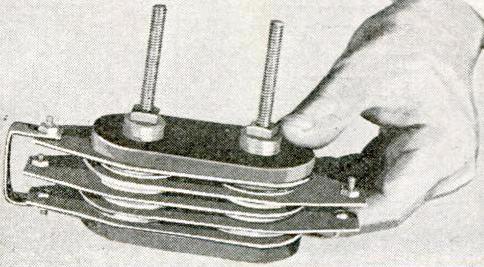

The second circuit is slightly safer, because it includes an isolation transformer. It’s still dangerous, because you’re still playing with 120 volts. It simply eliminates a few of the many possible methods of lethal electrocution. Like the other model, it drops the line voltage somewhat by passing the current through two light bulbs, in this case a 75 watt and a 25 watt in parallel. Since these bulbs probably wouldn’t glow brightly enough to see if the unit is energized, there is a test switch to temporarily remove the 75 watt bulb from the circuit. When the test button is pushed, the 25 watt bulb will provide a visual cue that the probes are correctly in place and the worms are on their way to the surface.

The article does contain a few safety warnings of its own. One of the descriptions starts with the self-evident comment that “the safety factor is the biggest problem involved in the use of house current.” It also warns: “Don’t take any chances by moving the probes when the unit is turned on.” If the energized probes are safely underground, the effects will presumably be felt only by the worms. And since the soil is not a perfect conductor, it’s probably not lethal to the worms. But if the probes are out of the ground while energized, then they pose a hazard to humans in the area.

The editors also add the caution: “Do not attempt to modify either of these circuits. If wired according to the schematics, they will provide [somewhat] adequate protection from the LETHAL 117-volt a.c. household line.”

One warning that’s not mentioned in the article bears repeating. It notes that if the ground is dry, then watering the ground first could improve performance. This stands to reason, since damp soil is obviously more conductive than dry soil. But it also highlights the fact that damp shoes (or bare feet) are better conductors than dry shoes. So if you insist, despite my warnings, to attempt this method of worm collection, please make sure you’re wearing dry non-conductive shoes.

And remember: Kids: Don’t try this at home!

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

![]()