From 1951-1963, U.S. broadcast stations were required to participate in CONELRAD, a system designed to alert the public to enemy attack, but also deprive enemy bombers of radio signals which could be used for navigation purposes. Under a CONELRAD alert, all stations would cease broadcasting on their normal frequencies. Designated stations would switch to broadcasting on either 640 or 1240 kHz. The result would be that listeners would be able to hear alerts, but enemy bombers would hear only a confusing jumble of signals on those frequencies.

From 1951-1963, U.S. broadcast stations were required to participate in CONELRAD, a system designed to alert the public to enemy attack, but also deprive enemy bombers of radio signals which could be used for navigation purposes. Under a CONELRAD alert, all stations would cease broadcasting on their normal frequencies. Designated stations would switch to broadcasting on either 640 or 1240 kHz. The result would be that listeners would be able to hear alerts, but enemy bombers would hear only a confusing jumble of signals on those frequencies.

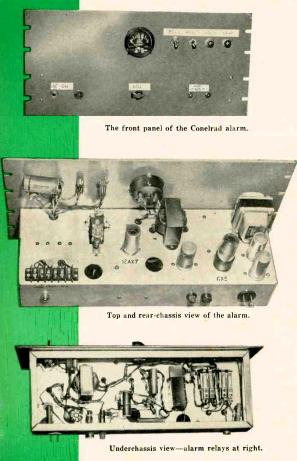

For the system to work, each station needed an alarm. For smaller stations, this would consist of an alarm tuned to another station in the area. If the primary station went off the air, then the smaller station would be alerted. If it turned out to be an actual alert, they would need to leave the air or switch to their designated frequency. Alarms were available commercially for broadcast stations, and simpler models were also available for hams, who were later required to participate in CONELRAD. Many hams built their own, and there were many plans published over the years. Sixty years ago this month, the October 1955 issue of Radio Electronics magazine carried the plans for the unit shown here, which was in use at WRFD, a Worthington, Ohio, 5000 watt daytime only station affiliated with Fram Bureau Insurance, with a format aimed at the agricultural market.

The author of the construction article was Harold Schaaf, the station’s chief engineer, who noted a critical defect in many of the existing CONELRAD alarms. Most of them depended on a normally open relay which would close in case of an alert. If the alarm circuit failed for some reason, there would be no relay action.

Schaaf noted that “such a system cannot be considered reliable, since it can go out of order without the operator knowing it.” Schaaf’s circuit instead included a relay that remained energized during normal operation. In the case of a circuit fault such as a failure of one of the tubes, the relay would de-energize, which would cause the alarm to sound, requiring the station operator to investigate. The result was what the title of the article described as a “failure-proof CONELRAD alarm.”

Like most other CONELRAD alarms, this one was hooked to the AVC circuit of a superheterodyne receiver tuned to the station being monitored. As long as there was an AVC voltage present, the alarm would remain silent. If the monitored station went off the air, the AVC voltage would disappear, which would trigger the alarm, which could consist of an external bell.

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

![]()