Photo courtesy of Inland Marine Radio History Archive website.

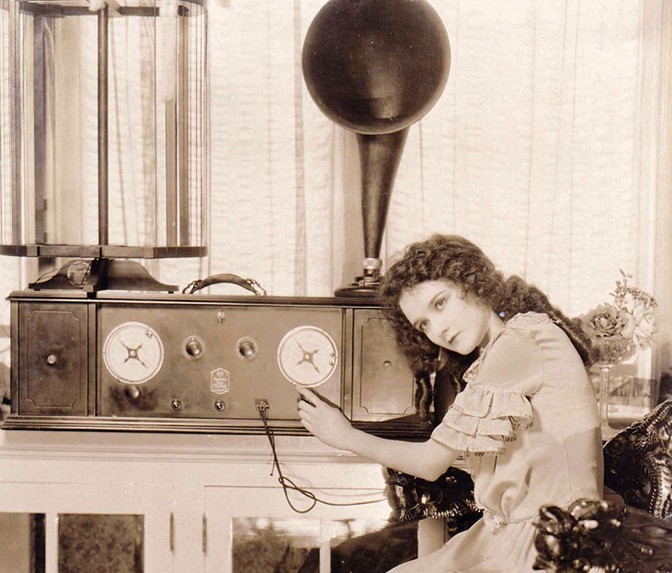

In an earlier post, we showed one silent movie star, Hope Hampton, soldering together a crystal set. A couple of years later, we see here another silent film star listening to the best set on the market. In this picture, Mary Philbin is listening to her RCA Radiola Superheterodyne model AR-812, which came out in 1924.

Mary Philbin and Lon Chaney in The Phantom of the Opera. Wikipedia photo.

Miss Philbin, who was about 22 years old when this photo was taken, was most famous for starring aside Lon Chaney in the 1925 film The Phantom of the Opera.

The radio, the RCA Radola Superheterodyne model AR-812, was the first home superhet on the market when it came out in 1924. This was a very advanced receiver for the day, and carried a hefty price tag of $269. (When converting prices to today’s dollars, I always remember that the 1920’s price would be paid with 269 silver dollars, which would be worth about $4000 today.) The set had six tubes, although most of them did double duty through the “reflex” principle. The oscillator tube also served as the detector, a scheme that initially caused problems for inventor Edwin Armstrong. Since the oscillator and the incoming signal were so close in frequency (the set had an IF of 40 kHz), they kept hopelessly interfering with one another. The problem was solved by mixing the incoming signal with the second harmonic of the local oscillator. This kept the two signals far enough apart so that the the same tube could at the same time oscillate at one frequency and detect at another.

The set used six UV-199 tubes and was battery powered. The batteries were housed behind the doors on either side of the front panel. The set had a built-in loop antenna, but it appears that Miss Philbin was intent on pulling in more distant stations with the external loop. As seen in the picture, the set drove a loudspeaker, which appears to be a Radiola UZ1320. As can be seen in the picture, the set sported a carrying handle. Since it was fully self-contained, it was a true portable, albeit a bit on the bulky side.

Armstrong and RCA jealously guarded the patents for the superheterodyne circuit. The nameplate on the front warns that it was “licensed only for amateur, experimental, and entertainment use, and only to extent indicated in attached notice.” Most of the electronics, including the transformers, were encased in wax to protect the components from moisture, and also to add an extra level of protection for the intellectual property concealed inside.

Mary Philbin came from a middle-class family in Chicago. She went to Hollywood in about 1920 after winning a beauty contest sponsored by Universal Pictures. In addition to Phantom of the Opera, she starred in the 1928 film The Man Who Laughs.

Like many other silent actors and actresses, she wasn’t successful after the transition to sound and had only a few roles early in the sound era, including dubbing her own voice in a talkie re-release of Phantom of the Opera. She was twice engaged, but never married. She made few public appearances after he departure from the screen, presumably preferring to stay home and listen to the radio. She died in California in 1993 at the age of 90 (New York Times Obituary).

The entire 1925 Phantom of the Opera, as well as other films featuring Mary Philbin, can be viewed at YouTube:

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Tom McKee of the Inland Marine Radio History Archive for allowing me to use the photo from the Archive’s website. That site, which will undoubtedly be the inspiration for future posts, contains a wealth of historical information about marine radio on the Great Lakes and inland waterways. I’m unsure of the origin of the photo, although it’s believed to be in the public domain.

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon ![]()